Amgen Inc. v. Sandoz Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2023) | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

An appellant’s burden on appeal is never easy but it is particularly difficult when the questions at issue are based on factual evidence. The appellate judiciary is loathe (generally) to second guess a district court judge on factual matters, in deference to the judge’s experience in observing the demeanor of the witnesses and how the evidence is introduced, and rebutted on cross-examination by opposing counsel over the course of the trial. These considerations were evident in the Federal Circuit’s decision in Amgen Inc. v. Sandoz Inc.* in which the Court affirmed the decisions below based on the District Court’s decisions on the facts.

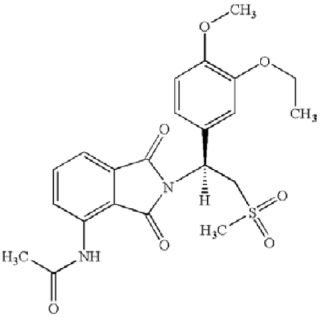

The case arose in ANDA litigation over Amgen’s apremilast product ((+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4-acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione), a phosphodiesterase-4 (“PDE4”) inhibitor, used for treating psoriasis and other related conditions and sold under the brand name Otezla®, having the structure:

Importantly, this compound is “stereochemically pure” (as noted by the Court, meaning it is one of two possible enantiomers, usually analogized for the chemical novice as right-handed or lefthanded). Three patents were at issue: U.S. Patent No. 7,427,638 (the ‘638 patent, wherein Amgen asserted claims 3 and 6); U.S. Patent No. 7,893,101 (the ‘101 patent, wherein Amgen asserted claims 1 and 15); and U.S. Patent Np. 10,092,541 (the ‘541 patent, wherein Amgen asserted claims 2, 19, and 21). The asserted claims are as follows:

The ‘638 patent (where the independent claims from which the asserted claims depend are set forth as they are in the opinion in italics);

3. The pharmaceutical composition [comprising stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3- ethox 4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4- acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt, solvate or hydrate, thereof; and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier, excipient or diluent, wherein said pharmaceutical composition is suitable for parenteral, transdermal, mucosal, nasal, buccal, sublingual, or oral administration to a patient], wherein said pharmaceutical composition is suitable for oral administration to a patient.

6. The pharmaceutical composition [comprising stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3- ethox 4-methoxyphenyl)-2- methylsulfonylethyl]-4- acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione, or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt, solvate or hydrate, thereof; and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier, excipient or diluent, wherein said pharmaceutical composition is suitable for parenteral, transdermal, mucosal, nasal, buccal, sublingual, or oral administration to a patient, wherein the amount of stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2- methylsulfonylethyl]-4- acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione is from 1 mg to 1000 mg, wherein the amount of stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4- methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4- acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione is from 5 mg to 500 mg], wherein the amount of stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4- methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4- acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione is from 10 mg to 200 mg.

The ‘101 patent:

1. A Form B crystal form of the compound of Formula (I):

which is enantiomerically pure, and which has an X-ray powder diffraction pattern comprising peaks at about 10.1, 13.5, 20.7, and 26.9 degrees 2θ.

15. A solid pharmaceutical composition comprising the crystal form of any one of claims 1 and 2 to 13.

The ‘541 patent:

2. A method for treating a patient with stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4- methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4- acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione, wherein the patient is suffering from psoriasis, the method consisting of:

(a) administering to the patient stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4-acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione in an initial titration dosing schedule consisting of

(i) 10 mg in the morning on the first day of administration;

(ii) 10 mg in the morning and 10 mg after noon on the second day of administration;

(iii) 10 mg in the morning and 20 mg after noon on the third day of administration;

(iv) 20 mg in the morning and 20 mg after noon on the fourth day of administration;

(v) 20 mg in the morning and 30 mg after noon on the fifth day of administration; and

(b) on the sixth and every subsequent day, administering to the patient 30 mg in the morning and 30 mg after noon of stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4- methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]- 4-acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione.

19. A method as in any one of claims 1–14, wherein the stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4 acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione comprises greater than about 98% by weight of the (+) isomer of 2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4-acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione based on the total weight percent of 2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4-acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione.

21. A method as in any one of claims 1–14, wherein the stereomerically pure (+)-2-[1-(3- ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4-acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione is administered in tablet form.

The District Court found that Sandoz failed to show by clear and convincing evidence that the asserted claims of the ‘638 nor ‘101 patents were invalid for obviousness but that it had established by clear and convincing evidence that the asserted claims of the ‘541 patent were invalid for obviousness. Infringement was stipulated for all asserted claims.

For the ‘638 patent, Sandoz proffered in support of its invalidity contentions U.S. Patent No. 6.020,358 and PCT Application No. WO 01/034606. The ‘358 patent disclosed a racemic mixture of 2-[1-(3-ethoxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-2-methylsulfonylethyl]-4-acetylaminoisoindoline-1,3-dione wherein the (+) enantiomer is apremilast. Both the ‘358 patent and ‘606 application teach that racemic mixtures (generally) can be resolved into their constituent enantiomers. But the District Court held that Sandoz had not shown that this art provided a reason or motivation for the skilled artisan to resolve the enantiomers to produce apremilast, because there was no disclosure that the (+) enantiomer had the desirable properties exhibited by the drug. Nor was the District Court convinced that the cited references would have produced in the skilled worker a reasonable expectation that the enantiomers could be successfully resolved even if there was a motivation to attempt to do so. The District Court also considered the objective indicia (otherwise known as secondary considerations as designated in the Supreme Court’s Graham v. John Deere Co. decision) of non-obviousness, in particular that “apremilast unexpectedly provided substantial improvement over previously known phosphodiesterase inhibitors in terms of both efficacy and tolerability.” In addition, the District Court found a nexus between these unexpected properties and the purified enantiomeric compounds recited in claims 3 and 6 of the ‘638 patent. The District Court further found that there was a long-felt but unmet need for the claimed compound, which could be orally administered and not accompanied by “risks and barriers” attendant on other PDE4 inhibitors used in these treatments (with the necessary nexus between the compound and this consideration). Similarly, the District Court found that other had tried and failed to develop other successful PDE4 inhibitors for such treatments, and that the commercial success of Otezla® supported a conclusion of non-obviousness.

Turning to the ‘101 patent, Sandoz argued that this patent was not entitled to the priority date of March 20, 2002, which was the filing date of a provisional application that provided its earliest priority date, but rather should be limited to the filing date of the application from which the ‘101 patent arose. This challenge was based on whether Example 2 of that priority application provided written description and enablement support for the asserted claims of the ‘101 patent. In addition, Sandoz asserted that Amgen’s predecessor in interest (Celgene) for the ‘101 patent had made representations in a corresponding European application that Example 2 produced another crystalline form of the compound (termed Form C) in addition to Form B claimed in the ‘101 patent. The District Court found that the ‘101 patent was entitled to its earliest priority date. In addition, the District Court held that with regard to Example 2, while not explicitly disclosing the final crystal form claimed in the ‘101 patent accepted the testimony of Amgen’s expert that the Example 2 disclosure inherently produced Form B of the claimed compound supported by “thirteen third-party experiments that replicated the procedures in Example 2 resulted in the crystalline Form B of apremilast.” As for the Form C question, the District Court was convinced be evidence that Form C required a toluene solvent to be produced and toluene was not disclosed as a solvent in the preparatory method disclosed in Example 2, chalking up any representations Celgene might have made regarding Form C to be “a mistake.” The District Court, finding that Sandoz’s obviousness arguments required a finding that the asserted claims of the ‘101 patent were not entitled to its earliest priority date, held that Sandoz had not satisfied its burden for invalidating the asserted ‘101 patent claims.

For the ‘541 patent, Sandoz asserted three prior art references: Papp (Papp et al., Efficacy of apremilast in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomised controlled trial, 380 LANCET 738 (2012)); Schett (Georg Schett et al., Oral apremilast in the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 64 ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY 3156 (2012)); and Pathan (Ejaz Pathan et al., Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis, 72 ANNALS OF RHEUMATIC DISEASES 1475 (2012)). The Papp reference disclosed clinical trial data using a five-day dosing regimen for apremilast having these details:

• Day 1: 10 mg first dose; 10 mg second dose

• Day 2: 10 mg first dose; 10 mg second dose

• Day 3: 20 mg first dose; 20 mg second dose

• Day 4: 20 mg first dose; 20 mg second dose

• Day 5: 30 mg first dose; 30 mg second dose

The Schett reference also taught the results of a clinical trial, wherein apremilast was administered at 40 mg daily doses (either in single dose or two 20 mg dosages). Regarding administration for treating psoriasis, this reference taught a “dose-escalation” protocol over the first seven days of treatment. Finally, the Pathan reference also taught a dose-escalation protocol beginning with 10 mg twice daily, titrating to 20 mg every two days until a dose of 30 mg twice daily was achieved on day 5, for treating ankylosing spondylitis. The District Court found that one of ordinary skill in the art would have been able to titrate apremilast administration as disclosed in these references and that this would have been a routine aspect of using a drug like apremilast for treating psoriasis. On this basis the District Court found that the asserted claims of the ‘541 patent were invalid for obviousness. Both Sandoz and Amgen appealed.

The Federal Circuit affirmed all the District Court’s findings in an opinion by Judge Lourie joined by Judges Cunningham and Stark. The bases for Sandoz’s appeal were that the District Court erred with regard to the ‘638 patent by failing to find motivation from the cited art and reasonable expectation of success regarding the (+) enantiomer that is apremilast. For the ‘101 patent, Sandoz argued that the District Court erred in finding the ‘101 patent was entitled to priority to its earliest priority application and its March 20, 2002 filing date. Sandoz’s argument for the ‘638 patent was that the existence of a racemic mixture provided the motivation to resolve it, that there were methods known in the art to do so (specifically, “chiral chromatography”), that regulatory agencies were exerting “pressure” on pharmaceutical companies to do so and that the fact that apremilast is a thalidomide analogue would have “taught toward” resolving the racemic modification produced by the cited prior art. Sandoz also argued that the District Court had “inappropriately relied” on testimony from Amgen’s expert regarding his difficulties in isolating enantiomers (albeit not apremilast) on the question of whether undue experimentation would have been required. Sandoz also asserted error because the District Court did not hold against Amgen statements in the ‘638 specification that methods for resolving the racemic mixture to produce apremilast were known in the art. Further error arose according to Sandoz because the District Court excluded evidence that Celgene had represented to a foreign patent office that the cited ‘358 patent reference disclosed stereochemically pure apremilast. Finally, Sandoz challenged the District Court’s determinations regarding the secondary considerations of non-obviousness.

The Federal Circuit rejected these assertions of error, finding no clear error in the District Court’s determinations that Sandoz had not established by clear and convincing evidence that the prior art gave the skilled worker reason or motivation to resolved the racemic mixture produced in Example 12 of the cited ‘358 patent reference, or that the skilled worker would have had a reasonable expectation of success in so doing even if motivated to do so, or that the (+) enantiomer would have the desired properties it was shown to have in the ‘101 patent. The panel’s holding in this regard recognized the District Court’s reliance on testimony from both parties’ experts and its weighing thereof. The opinion also held that the District Court did not err in not holding Amgen to the representations made by Celgene because as the opinion notes “Sandoz’s own expert conceded that the formation of chiral salts was not a viable method for separating the Example 12 enantiomers contrary to the statement in the specification,” using this testimony and the Court’s recognition of “the unpredictable nature of resolving racemic mixtures and the district court’s acceptance of Amgen’s expert testimony as credible” to distinguish over PharmaStem Therapeutics, Inc. v. ViaCell, Inc., 491 F.3d 1342,1362 (Fed. Cir. 2007), asserted by Sandoz in support of its argument. The panel also agreed that the District Court’s consideration of the “strong” objective indicia of non-obviousness were not made in error, particularly in view of expert testimony regarding the 20-fold difference in potency between the racemic modification and the purified enantiomer (which, because the (+) and (+) enantiomers were present in a ratio of 50:50 in the racemic mixture was far greater than the “expected” doubling upon separation of the enantiomers). (The Court noted in this regard that such conclusions were made on a fact-specific basis and that there was “no specific fold-difference that defines [obviousness].”) The opinion similarly reviewed and affirmed the District Court’s findings concerning its findings for the other objective indicia.

Turning to the ‘101 patent, the panel found no clear error in the District Court’s determinations of whether that patent was properly entitled to the priority date of the earliest claimed priority document. Sandoz argued that Amgen should not have been permitted to rely on inherent disclosure under circumstances where the priority document did not disclose in the priority document the X-ray powder diffraction pattern that characterized Form B (apremilast) as claimed in the ‘101 patent (particularly because Celgene relied upon that pattern to distinguish the ‘101 claims over the prior art). Sandoz also cited as error the District Court’s disregard for Celgene’s “affirmative admissions” regarding preparation of Form C crystalline apremilast using Example 2 in the priority document.’

The Federal Circuit disagreed and affirmed the District Court’s findings that Sandoz failed to establish by clear and convincing evidence that the asserted claims of the ‘101 patent were invalid for obviousness. The panel cited the series of thirteen experiments proffered by Amgen showing that Example 2 of the priority document produced Form B apremilast and that Sandoz did not provide any evidence that Example 2 produced any other crystalline forms of the compound. While recognizing that inherency imposed a strict standard, citing Bettcher Indus., Inc. v. Bunzl USA, Inc., 661 F.3d 629, 639 (Fed. Cir. 2011), the Court stated in its opinion that they did not need to reach the inherency question because Amgen had shown by its evidence, Sandoz’s lack of any contrary evidence, and expert testimony that Example 2 of the priority provisional application produced Form B apremilast. The panel also credited Amgen’s distinction regarding Form C and the need for a toluene solvent to produce this crystal form as establishing without clear error that the absence of this reagent in Example 2 of the priority document precluded its presence in the apremilast produced using this method, regardless of any representations predecessor Celgene might have made to a foreign patent office.

With regard to Amgen’s grounds and arguments for appeal, that the District Court erred in finding the asserted claims of the ‘541 patent obvious based on the prior art dosing schedule, the Federal Circuit affirmed the District Court’s affirmance of the finding that the asserted claims of the ‘541 patent were obvious. The panel credited the District Court’s reliance on expert testimony “establishing that it was well within a skilled artisan’s ability to titrate an apremilast dose for a patient presenting with psoriasis and that doing so would have been a routine aspect of treating psoriasis” and that the claimed dosing regimen (“initiating treatment at 10 mg and increasing toward a 30 mg twice-daily target dose in 10 mg increments”) would have been obvious over the cited art (Papp and Schett). The opinion cites Genentech, Inc. v. Sandoz Inc., 55 F.4th 1368, 1376–77 (Fed. Cir. 2022), for the principle, applicable here, that “varying a dose in response to the occurrence of side effects is a well-known, standard medical practice that may well lead to a finding of obviousness” and thus found no clear error in the District Court’s determination that the asserted claim of the ‘541 patent are obvious.

The Court has addressed the question of whether prior art disclosing racemic mixtures of stereochemically distinct compounds can render obvious claims to purified enantiomers thereof. See, for example, Aventis Pharma Deutschland GmbH v. Lupin, Ltd.; Sanofi-Synthelabo v. Apotex, Inc.; Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; Trying to Understand What’s Not Obvious about What’s “Obvious to Try”). This decision is consistent with these earlier examples and illustrates the case-by-case nature of the exercise.

* The caption is an abbreviation of the defendants, which included in addition to Sandoz Zydus Pharmaceuticals (USA) Inc. (a co-appellant) and Mankind Pharma Ltd., Torrent Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Limited, Macleods Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Msn Laboratories Private Ltd., Actavis LLC, Prinston Pharmaceutical Inc., Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Heritage Pharmaceuticals Inc., Aurobindo Pharma Ltd., Aurobindo Pharma USA, Inc., Annora Pharma Private Limited, Hetero USA, Inc., Cipla Limited, Alkem Laboratories Ltd., Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Inc., Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Ltd., Amneal Pharmaceuticals LLC, and Pharmascience Inc., Defendants

Amgen Inc. v. Sandoz Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2023)

Panel: Circuit Judges Lourie, Cunningham, and Stark

Opinion by Circuit Judge Lourie