A Reorientation in the Discretionary Powers of the European Commission under the Digital Markets Act – Solutions from Digital Constitutionalism

Key Message

The discretion granted to the European Commission is crucial to the implementation and enforcement the Digital Markets Act (). The article argues that discretion can be used to enhance fundamental rights within the rigid structure of the DMA. Conversely, it is postulated that it can also be employed to enhance fundamental rights within the confines of the DMA’s inflexible structure.

The types and role of discretion in the Digital Markets Act

The DMA acknowledges the European Commission’s various forms of discretion, which it exercises as the sole enforcer (for an overview of the different types of discretion, see, among others, Oliveira and Dias, 2022

and Goncalves, 2019).Firstly, there is the discretion to act which allows the relevant authorities to take action or refrain from doing so in response to a specific behaviour or request. This is illustrated by the discretion granted to the European Commission in order to determine whether the measures taken by the gatekeeper are effective (see Article 8(3) DMA

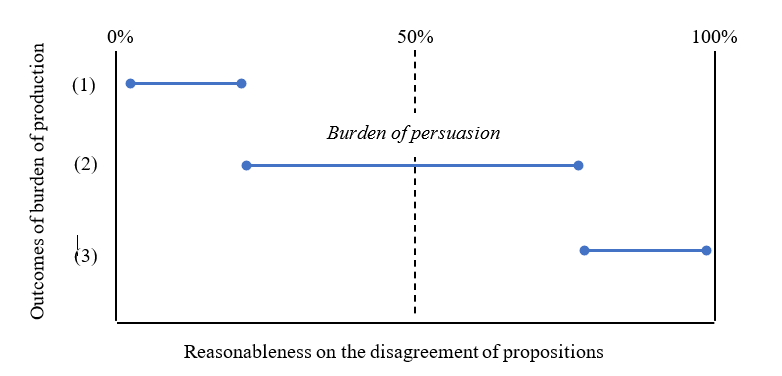

). An additional illustration can be found in Article 27(2) of the DMA, which grants National Competition Authorities (‘NCAs’) and the Commission full discretion to follow up on (or refrain from responding to) information received from third parties (including business users, competitors, or end users of a gatekeeper’s core platform services).Secondly, there is the discretion of choice, which allows the freedom to choose between two or more courses of action that are provided for in the legislation. In the context the DMA, a good example is the relationship between the specification process outlined in Article 8 and non-compliance procedures outlined in article 29 of the DMA

. In fact, based on the compliance reports provided by the gatekeepers, (see Article 11 DMA) the Commission can either initiate a process to specify what the gatekeeper is expected to do to ensure effective compliance, thereby favouring a dialogical and cooperative enforcement, or alternatively proceed directly to a non-compliance finding under Article 29 of DMA. In the second scenario, there is a greater degree of discretion for the Commission to choose a suitable course of action. The Commission can choose to end the procedure without adopting any decision of non-compliance. (See Article 29(7) DMA) The Commission could also adopt a non-compliance decision. In such a case, the gatekeeper would be required to cease the violation in question and refrain from any further similar actions within a reasonable timeframe. The gatekeeper will also be required to explain how it intends on complying with the decision (see article 29(5) DMA). The Commission can impose an administrative fine on the gatekeeper who is not in compliance (see Article 30 DMA). In each of the scenarios above, the Commission exercises discretion in the context punitive enforcement. This approach appears to be consistent with the stance taken by the European Commission in relation to the initial compliance reports submitted by the gatekeepers (for a detailed analysis, Ribera Martinez, 2024).Thirdly, creative discretion or the discretion to create provides the administration with the freedom to design concrete solutions within the applicable legal limits. In this case, the law is limited to predicting and defining a result. The administration is then free to determine the appropriate process or measure to achieve it. It is still a form discretion, but it differs in that the options are not predetermined by law. They are the result of the administration. This creative discretion can be illustrated by the interim measures that the EC may implement to prevent serious and irreparable damages for business users or the end users of gatekeepers, until the conclusion of the investigation. In Article 24 of DMA

, the European Commission is empowered to exercise this power in cases where they have prima facie established the gatekeepers’ failure to comply with their obligations. The DMA does not define or specify specific interim measures. Therefore, there is a certain amount of flexibility in designing and choosing them. In this context, the reality that is to be regulated requires the formulation of technical judgments about the existence, value, and probability of a particular situation. The complexity of the DMA allows for this type of discretionary power to be exercised across the board. However, it is believed that it will not be used primarily in relation to questions of “if” or “when”, which are often defined in strict legal terms in the DMA, but rather in relation the ‘how’. The content or substance of Commission actions and decisions. This type of discretion is evident in the contexts of market investigations. It is worth noting that companies can be designated as gatekeepers if the quantitative thresholds specified in Article 3(2) DMA have not been met (see Article 3(8) DMA

). In fact, while the legislator sets out the final objectives of an analysis and the elements that the Commission must consider, the designation of a company as a “gatekeeper” requires the application of scientific, technical, and specialised expertise. In this regard, the Commission is acknowledged for its particular sapiential, especially in light of its experience in relation to digital markets under Articles 101 and 102 of the TFEU. The DMA is aware of the importance of exercising discretion within limits and upholding fundamental right in a manner which guarantees both the efficacy and optimisation of fundamental rights. In addition to references made in the recitals of the DMA entitled “Right to be Heard and Access to the File”, the article 34(1) of this DMA sets out that the Commission must provide the undertaking with an opportunity to be heard prior to the adoption of any decision pursuant to articles 8, 9(1) and 10(1) and articles 17, 18, 24, 25 and 29 and Article 31(2). In addition, according to the case law of the General Court even decisions adopted pursuant to other Articles (for instance, the decision where the Commission designates an enterprise as a gatekeeper after rejecting its arguments attempting to call into question the assumptions laid down in Article 3(2) DMA), must respect the fundamentals rights and adhere the principles recognised by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (“CFR

“). This is exactly what follows from Article 34(4), which refers to “any proceeding”, as well from Recital 109 in the DMA

. The mention by the Court was not essential, in any case, as it is inherent to the idea of fundamental rights.

Indeed, as the General Court emphasises in Bytedance v Commission

, “according to the case-law, the rights of the defence are fundamental rights forming an integral part of the general principles of law whose observance the Courts of the European Union ensure. This general principle of EU Law is enshrined in Article 41(2)(a), (b) and (c) of the Charter. It applies when the authorities intend to adopt a measure that will adversely impact an individual. Therefore, observance is required of the right-to-be heard even if the applicable legislation doesn’t expressly provide such a procedural requirement. In accordance with Article 41, every person has a right to have their affairs handled impartially and According to the case-law, that right guarantees every person the opportunity to make known his or her views effectively during an administrative procedure and before the adoption of any decision liable to affect his or her interests adversely” (see para 340ff).In conclusion, it can be stated that discretion is not synonymous with either a monopoly in decision-making or arbitrariness. The exercise of discretion, no matter what form it takes or who exercises it, is subject to both external (such as the public interests or interests determined by legislators and entrusted by the Commission) and interior limits. These include, first and foremost, fundamental rights, which, in the European Union (‘EU’) area, are not even limited to those enshrined in the CFR (see Article 6 Treaty on European Union (‘TEU’).It is our contention that the potential of administrative discretion can be harnessed to ensure the practical realisation and optimisation of the fundamental rights and interests at stake. In fact, it appears that the European Commission used its discretion to free itself from the rigidity of the DMA in its first designation decision (for more insights, please see Ribera Martnez, 2024

). It is thus proposed that the Commission’s discretion to act and choose, as well as its creative and technical discretion, can address the flaws of the DMA in terms of rigidity and participation.To illustrate, in the event that compliance reports submitted by gatekeepers are deemed inadequate in light of the DMA’s objectives, rather than automatically initiating non-compliance proceedings, the Commission could and should engage in specification (at least with respect to some of the obligations set forth in the DMA). In all cases, EC must choose the outcome that best respects and fulfills the positive duties arising from fundamental rights. The Commission seemed to have followed this path in regard to the right of being heard following the entry into effect and applicability DMA. As the General Court ruled in Bytedance/Commission[…], the “applicant was heard at least four times prior to the adoption of contested decision”. First, there were at least four meetings between the applicant and Commission before the notification. […] Then, after the notification on 3 July 2023 was submitted, the Commission sent to the applicant their preliminary views on the 26th of July 2023. Lastly, on 17 August 2023, another meeting between the applicant and the Commission took place.” (see para 345).

The EU Courts’ subsidiary role

It is acknowledged that the Commission may exercise its discretion in a manner that differs from the aforementioned interpretation. A fair balance could also require the Commission to implement a solution, measure, or decision that is perceived by the gatekeeper as disproportionately affecting its rights. This does not negate or diminish the necessity of judicial oversight in discretionary adjacent binding areas. In these cases, merit, convenience, and/or expediency would be the determining factors, and they are not susceptible to judicial control. The separation of powers – which is also an aspect of the rule-of-law and democracy, as values upon which the Union was founded (see TEU)- would be in danger. It is clear that all forms are ultimately subject to law. All power is ultimately limited, regardless of how open the rule is. Fundamental rights serve as both a shield and sword to limit all power. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that if the legislature and the executive branch exercise Force and Will, the judiciary will be expected to exercise judgement (see Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo

).Even if companies were not recognised as entitled to fundamental rights (which is not the position we are taking), procedural fundamental rights are considered to afford protection to any individual who is a party or is directly affected by administrative or other proceedings. In fact, fundamental rights are not only the cornerstones of subjective individual positions, but also serve as procedural standards, and precipitates for constitutional values that are common to both domestic and EU jurisdictions. (For an overview, please see, among other things, Ribeiro[…]). When viewed in their objective dimension or even as principles, fundamental rights impose positive obligations on both to the legislature and the executive branch, independent of the subjects (for further insight into the particular importance of fundamental rights and access to information in the context of DMA enforcement, see Helminger and Hornkohl, 2024).

In order to ensure the effective protection of the law, the Court of Justice requires a fair trial that is independent of the executive branch (see, among others, Netherlands and Van der Wal/Commission

). This does not exclude the possibility that the enforcer’s view could influence the judiciary’s decisions, but it is important that the courts maintain their substantive independence in the sense that executive decision are not perceived to be binding on the judiciary. This approach is the only way to ensure that the public and those seeking justice can continue to have confidence in the judicial process. While the Commission has a large degree of discretion when it comes to making factual determinations, they must be supported by evidence. It is up to the courts to determine the extent of the discretion that has been granted to a particular authority by statute. The judiciary can also check the impartiality and proportionality in the actions taken by the European Commission. In relation to fundamental rights it is important to note, that according to Article 52 of CFR

any restriction to the exercise of rights and liberties recognised in the CFR

must be provided by law, respect their essential content, and adhere to the principle of proportionality. This principle states that any restriction on the rights and liberties of individuals must be both necessary and proportionate. This principle and guarantee of judicial oversight also applies. It is not policymaking; rather, it is fundamental rights adjudication.It is our contention that this is the manner in which the European Commission’s discretion in the DMA must be perceived.