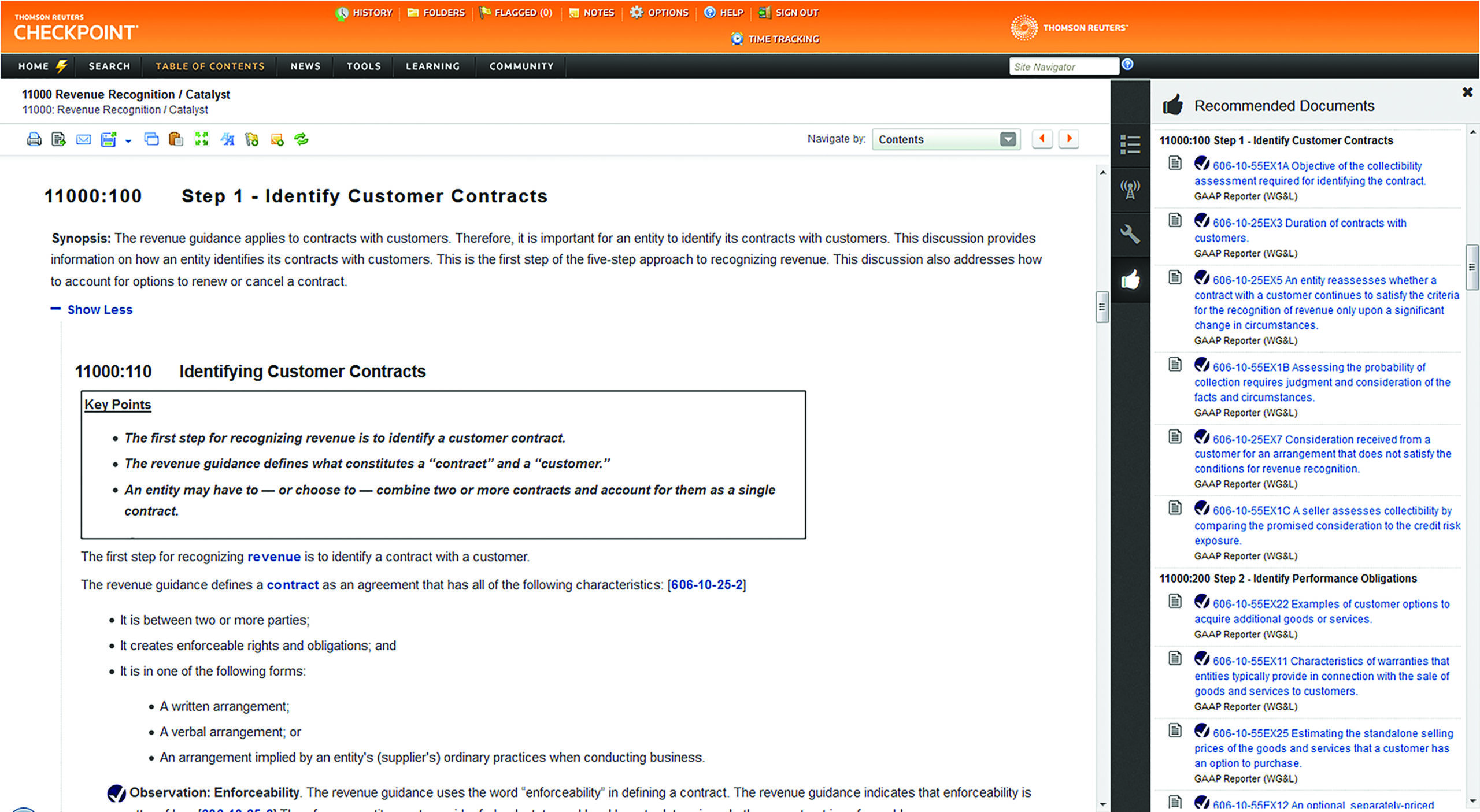

A New Solution for Taxing Cryptocurrency Staking

Taxing digital assets poses many tax policy puzzles. So many, in fact, that the Senate Finance Committee recently asked for advice on how to do it.

I have a new solution for one puzzle: how to tax the income people earn by staking crypto tokens. In a staking system, token holders pledge (i.e., stake) their tokens so they can help process and validate blockchain transactions. Stakers thus replace traditional intermediaries like banks or credit card companies. In return, they get rewarded with additional tokens.

A good place to start the puzzle is to ask how we tax similar economic activities. That benchmark is straightforward. Stakers provide a service (validating blockchain transactions) in return for compensation (more tokens). If we want to treat them like other service providers, we should tax them on their net income. Stakers should pay ordinary income taxes on the rewards they receive and get deductions for the expenses they incur.

Staked tokens should generate tax deductions

Some expenses involved in staking, e.g., the costs of running computers, are obvious. But there is also a non-obvious expense: cost recovery. Staked tokens are a type of intangible property used to generate income. Staked tokens should therefore qualify for the same amortization deductions other intangibles, like franchise rights, receive.

Alternatively, policymakers could create a new tax deduction that reflects how the economic capability of staked tokens depreciates over time.

The idea that staked tokens are intangible property worthy of tax deductions may be surprising. People often discuss cryptocurrencies as though they are some sort of financial asset. Not literally a currency for tax purposes, but still financial property.

With rare exceptions, financial assets don’t get amortization or depreciation deductions. Nor should they. People buy and sell them, exchange them for goods and services, offer them as collateral for loans, or simply hold them. But they don’t use them to produce any goods or services.

Staking changes that. The owner gives up their right to use tokens for financial transactions and in return gets to earn rewards by validating blockchain transactions. Staking thus transforms tokens into productive, intangible assets. In tax jargon, tokens are placed in service to produce income.

Bitcoin validates transactions with a proof-of-work mechanism. But many other blockchains—Ethereum and Tezos, for example—do it using proof-of-stake, which requires fewer resources and less electricity.

The opportunity to validate transactions is shared across people based on how many tokens they stake. When they validate transactions correctly, stakers get newly-issued tokens as a reward. But if they validate transactions poorly, they may lose some staked tokens as a penalty. These incentives encourage stakers to operate the decentralized network securely.

Staked tokens are thus the blockchain equivalent of franchise rights or taxi medallions. If you want to serve branded fast food, you need a franchise right. If you want to collect cab fares in New York City, you need a medallion. And if you want to validate transactions on a proof-of-stake blockchain, you need staked tokens.

We have clear rules for cost recovery for franchise rights, taxi medallions, and many other types of intangible property. Under Section 197, taxpayers can amortize the original cost of those intangibles over 15 years.

The simplest way to handle staked tokens would be to treat them the same way. Congress could add staked tokens to the list of Section 197 intangibles. Or the IRS could recognize staked tokens as the blockchain version of a franchise right. Either way, stakers would get amortization on par with other service providers who use intangible property. But only as long as their tokens remain staked. When a person retakes control of their tokens, the deduction would end.

Newly-created tokens compete with existing tokens for staking rewards

You might wonder whether staked tokens deserve this treatment. Does their productive capacity decline over time? The answer is yes. The issuance of new tokens causes staked tokens to depreciate. Each new token can itself be staked to offer validation services. That competition reduces the economic capability of existing tokens.

Suppose a blockchain increases its token supply by 5 percent each year. Tokens that could validate 10 percent of transactions this year might be able to validate only 9.5 percent next year. And only 9 percent the year after. And so on. New staked tokens cause existing staked tokens to gradually become obsolete. Without some unforeseen improvement in market conditions, a person who stakes the same number of tokens each year would see their revenue decline.

Policymakers have the option of looking beyond the rough justice of Section 197 amortization. They could allow deductions that reflect the actual decline in staked tokens’ economic capability. There are some technical details in how you measure this. But the basic idea is simple. If token supply expands 5 percent one year, stakers could get a deduction of 5 percent of the cost of their tokens. If policymakers prefer a depletion-like approach, the deduction could be 5 percent of their staking revenue.

These approaches would be more administratively complex than 15-year amortization. But they would allow deductions to more closely track the depreciation experienced by staked tokens.

Two other approaches have dominated public debate. Traditional tax experts recommend taxing staking rewards as ordinary income at receipt (e.g., here and here). But to my knowledge, they have not suggested options for cost recovery. Senators Lummis and Gillibrand, along with some crypto proponents (e.g., here and here), have recommended taxing staking rewards only when the tokens are eventually sold.

Both approaches have the virtue of administrative simplicity. But neither is consistent with the way we tax other service providers.

If consistency is a goal, policymakers should chart a middle course. Stakers should be taxed on their net income, not their gross income. Stakers should pay ordinary income tax on their staking rewards. And they should get cost-recovery deductions for the staked tokens that made those rewards possible.

.png)