A Few Things that USPTO Could Do to Simplify Patent Prosecution | McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office handles hundreds of thousands of patent applications per year, as well as various types of administrative patent proceedings. While the USPTO has made incremental improvements in its examination practices and IT systems to streamline applicant workflows, there are a number of relatively small changes that it could employ to reduce applicant time and expense. Both substantive and procedural, these changes would clarify certain aspects of examination while eliminating redundant paperwork. The net outcome of these changes would be a reduction in cost for applicants — namely, less time spent by patent attorneys, agents, and paralegals, leading to lower overall attorneys’ fees.

The items below are not intended to be a comprehensive listing, and come with the caveat that there would be an upfront cost for the USPTO to make these changes. Nonetheless, the cost savings, when amortized over millions of transactions per year, are likely to be significant.

1. Explicitly provide the examiner’s claim construction in Office actions

In order to evaluate an application’s claims against the prior art and to determine whether they comply with other requirements (e.g., written description, enablement, and patent eligibility), the examiner is required to construe the claims — to assign a meaning and scope to claim terms.

Nonetheless, it is rare for an examiner to provide their claim construction in an initial office action. In many cases, the first opportunity that the applicant has to learn of the examiner’s construction is in an interview or in a subsequent Office action.

This results in applicants and examiners talking past each other in office actions and responses. All too often, the examiner has one construction in mind, and the applicant has another. Until these parties at least become aware of the other’s thinking, it may be difficult to progress the application. In many examples, one or two Office action cycles could have been eliminated if the examiner’s claim construction was readily available from the outset.

Therefore, each Office action should have a dedicated section in which the examiner provides a construction for any non-trivial claim terms to which the examiner is applying an interpretation beyond those terms’ plain and ordinary meaning. It should be recommended that the examiner construe all claim terms if possible, as doing so can only help accelerate prosecution.

In turn, the applicant would have an opportunity to, on a term-by-term basis, either accept the examiner’s construction or rebut the examiner’s construction with one of its own. But at the very least, the applicant would have a better understanding of why the examiner finds certain prior art references to be relevant to the claims.

As they say, you cannot have a meaningful debate with someone unless you can agree on a common set of facts.

2. Use claim charts to apply the prior art to claim elements

Current USPTO Office actions reject claims based on a narrative from the examiner. These narratives are typically in paragraph form, providing a claim element, citations to sections of prior art references that are purportedly relevant to the element, and any further reasoning from the examiner.

This narrative form can be confusing to follow in the best of cases, as sometimes the examiner’s reasoning is unclear or ambiguous. But where it really breaks down is when the examiner uses two or more references against the same claim element. Discussion of these references might be split across several different parts of the Office action, making it difficult for the applicant to grasp the examiner’s logic. Also, it is not uncommon for the application of the references to various parts of the claim element to be imprecise.

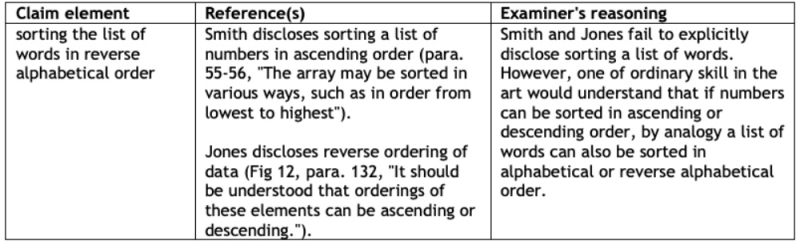

As an example, consider the claim element, “sorting the list of words in reverse alphabetical order.” Suppose that the examiner has concluded that disclosure within the Smith and Jones references render the element obvious. In a traditional Office action, the examiner might write:

Smith discloses sorting a list of numbers in ascending order (para. 55-56, “The array may be sorted in various ways, such as in order from lowest to highest”).

[ Several paragraphs later . . .]

Jones discloses reverse ordering of data (Fig 12, para. 132, “It should be understand that orderings of these elements can be ascending or descending.”).

[ Several paragraphs later . . .]

Smith and Jones fail to explicitly disclose sorting a list of words. However, one of ordinary skill in the art would understand that if numbers can be sorted in ascending or descending order, by analogy a list of words can also be sorted in alphabetical or reverse alphabetical order.

While the grounds of this example of examiner reasoning might be solid, the application of the references to the claim element requires that the applicant look in three different locations to understand the full extent of the examiner’s position.

The same text appearing in a claim chart would be much more clear and concise. An example follows:

This format puts all discussion of each claim element in one place, reducing the amount of effort and guesswork that goes into attaining understanding of an examiner’s position. Further, the claim chart format has the additional advantage of making it very easy to ensure that all claims elements are considered by the examiner. It is not unusual for examiners to unintentionally miss a claim element, especially when the claim is complicated. Also, this format prompts the examiner to provide their reasoning rather than just cite the prior art.

3. Allow applicants to send calendar invites to examiners and to use popular conferencing tools

Currently, setting up examiner interviews can be a bit of a hassle. The applicant needs to contact the examiner by phone, find a suitable time, and then prepare and send an interview agenda to the examiner. All this for a telephone interview. The USPTO supports video conferences with examiners, but only using WebEx and through a more onerous setup process.[1]

As we have learned in the last two-plus years of COVID, conferencing tools such as Teams and Zoom have become largely ubiquitous and are efficient and reliable ways of holding remote meetings. Further, they support very simple screen sharing capabilities. While it is understandable that some examiners might not have working camera setups, the applicant and examiner seeing each other is not required.[2] It can be very helpful to just share a view of the applicant’s specification and drawings, and/or the prior art documents.

In an ideal scenario, the examiner’s email address would be printed in each Office action. The applicant would then be able to send a Teams or Zoom calendar invite to the examiner. The examiner would have the right to accept the invitation, propose an alternative time, or decline the video conference and fall back on a telephone interview. During the call, screen sharing could be used to facilitate the discussion.

4. Stop asking applicants to provide information that the USPTO already has

There are numerous filings that applicants make from time to time that require that the applicant provide information to the USPTO that is already in an application’s file wrapper, or is otherwise in USPTO databases.

Requests for corrected filing receipts typically require that the applicant provide copies of edits to be made to the application’s filing receipt as well as its application data sheet (ADS). In some cases, these edits take the forms of manually adding text to a PDF document. For simple changes, such as adding or removing an inventor or correcting a clerical error, only a single form should be required. Likewise, any filing currently requiring a chain of title should not make the applicant inform the USPTO of the chain of title if it already exists in the application’s file wrapper.

An even more onerous example is Information Disclosure Statement (IDS) forms that require that the applicant enter the patent number or application number, filing or publication date, and applicant or inventor of each cited US patent or application. Doing so for a lengthy IDS is very time-consuming and error prone.

Since the USPTO has all of this information, the applicant should be able to enter just the patent number or application number into a web-based interface and let the USPTO’s system fill out the rest. Better yet, let the applicant put all of this information into a CSV or flat file and upload it to the USPTO’s filing portal. The portal can automatically fill in the required information and/or flag any errors. Given that long IDSs can sometimes take several hours of paralegal and attorney time to complete and file, this change alone would go a long way toward making patent prosecution more affordable.

The USPTO’s current web-based ADS form is an example of how the USPTO has the ability to auto-populate forms. The same should be done for as many forms as possible.

5. A few odd and ends

Finally, here are a few quick hits that round out the wish list.

The USPTO currently downsamples the resolution of drawings. Why? It is my understanding that the USPTO keeps the high-resolution versions somewhere for publication and printing purposes. So why use inferior versions in PAIR? In some cases, this can lead to objections to the drawings for lack of readability even though the submitted versions were readable. Given today’s storage, processing, and networking capacity, the rationale for such downsampling seems moot.

In appeals to the PTAB, there should be no new grounds for rejection in the examiner’s answer. Instead, if the examiner wishes to provide such new grounds, prosecution should be reopened and the examiner should do so in an Office action. This would motivate examiners to more thoroughly consider how to use the prior art against the claims. As an alternative, applicants could be given the opportunity to allow the appeal to continue to the PTAB when they wish to rebut the examiner’s new grounds without reopening prosecution.

Finally, a very small nit. Get rid of the 150-word limit on abstracts. Since abstracts are usually just abridged versions of the broadest claim submitted, they do not serve much of a purpose anyhow. Increasing this limit to, say, 250 or 300 words would make the transfer of the broadest claim into prose less likely to cause omission of any of that claim’s features.

[1] The USPTO touts its Automated Interview Request (AIR) form for requesting interviews without first calling the examiner, but I have found that examiners often do not notice these requests and you end up having to follow it with a phone call anyway.

[2] The unwritten rule of video conferences these days is that no one should be forced to turn on their camera.