A Cursory Overview of Self-Preferencing in Korea: NAVER Shopping

It would no longer be surprising to see competition or regulatory authorities blaming digital platforms for favouring their own services on their own platforms. In particular, in Europe, seeing the General Court’s Google decisions (see e.g., Johannes Persch’s blog posts on Shopping and Android) and the self-preferencing obligation of the Digital Markets Act (see, e.g., Article 6(5) of the Digital Markets Act, ‘DMA’), it looks that the epithet self-preferencing is now well-established as a legal concept, albeit controversial.

In fact, the triumph of the self-preferencing doctrine is not confined to Europe but is found in many other jurisdictions as well. Korea is a case in point. On December 14, 2022, the Seoul High Court decided that the Korean competition authority (i.e., Korea Fair Trade Commission, ‘KFTC’) was right to sanction “self-preferencing” as abuse of dominance in NAVER shopping (Decision No. 2021-027), the Korean equivalent of Google Shopping (AT.39740).

Following the decision, on January 12, 2023, the KFTC released the Guidelines for Review of Abuse of Dominance by Online Platform Operators (“Platform Guidelines”), declaring in confidence that self-preferencing can be a violation of Article 5 of the Korean competition law, i.e., Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (‘MRFTA’).

How has the concept of self-preferencing so successfully dissolved into Korea’s competition law and policy? And how is the doctrine being developed in Korea at the moment? Here, in this blog entry, I will try to overview the process of the self-preferencing concept becoming settled as a legal doctrine in Korea, through the NAVER Shopping case.

NAVER Shopping, Inspired by Google Shopping

It all started with Google Shopping.

For Korean competition law scholars, the European Commission’s 2017 Google Shopping decision was a surprise. And it sparked controversy. Up until then, there had been a broad consensus in Korea, to the best of my knowledge, that so-called self-preferencing is a typical manifestation of competition based on merits rather than an illegal restriction of competition, unless it amounts to abusive refusal, tying, or bundling. Indeed, in 2013, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (‘FTC’) found that the same practice of Google did not violate the U.S. antitrust law, i.e., Section 5 of the FTC Act (the prohibition of unfair methods of competition). This US case had been very favourably cited in many scholarly articles in Korea, at least until the release of the EU’s Google decisions.

For the Korean competition authority, however, the European Commission’s decision might have come as a good surprise since the authority was also looking into several practices by a local search platform, i.e., NAVER. I have no idea whether there was a ‘meeting of minds’ between the two enforcers at the time, but apparently, there were significant parallels between their enforcement activities.

While the European Commission (under Joaquín Almunia) initiated its probe into Google’s practices in 2010 and discussed commitments in 2013-2014, the Korean watchdog embarked on an investigation into the local search platform’s practices in May 2013 and closed the case with commitments in 2014. Despite the commitments, the KFTC continued to look at the search bias issue, and, after the 2017 Google Shopping decision of the European Commission (under Margrethe Vestager), it opened a new proceeding against NAVER and decided to sanction self-preferencing by the local dominant search platform in 2020.

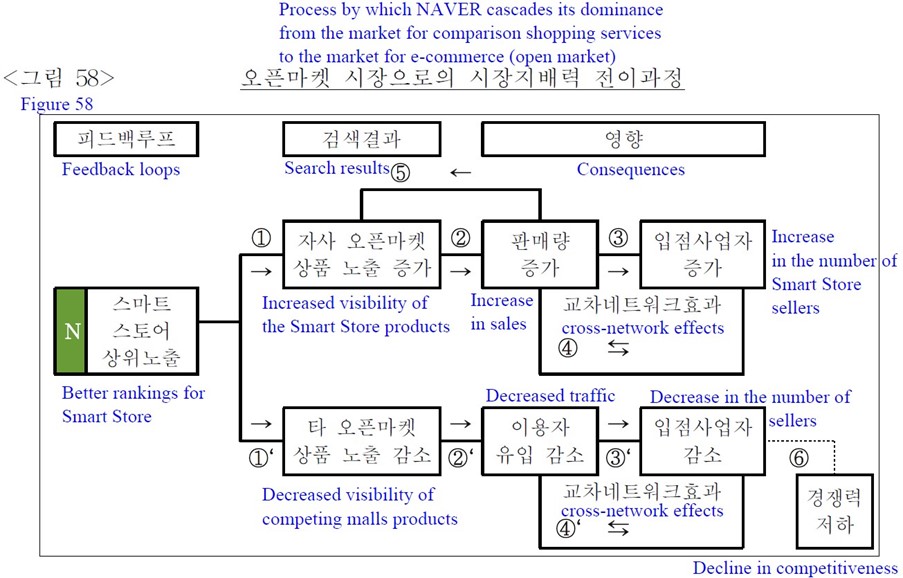

In its decision, the KFTC found that NAVER, as a dominant comparison shopping service provider, unjustly leveraged its dominance in the market for e-commerce (open market) services through the means of algorithm manipulation under which NAVER’s open market service (called “NAVER Smart Store”) was preferred in the comparison shopping search results and received more traffic. To underpin its argument, the KFTC showed the reinforcing feedback loops between the practice, sellers’ choice, and exclusionary effects, as below:

* English translation was added.

Following this logic, the agency imposed a corrective order and a fine of approx. 26.6 billion won (approx. 20 million euros) to NAVER.

Similarities and Differences Between NAVER Shopping and Google Shopping

There were many similarities between the two cases, the KFTC’s NAVER Shopping and the European Commission’s Google Shopping.

They both paid attention to the tech firms’ very entrenched dominant position regarding search services. The search engine services provided by Google and NAVER were both considered essential and very necessary for competitors in the downstream market. Still, in both cases, the essential facility doctrine was not applied. Also, in both decisions, the dominant search engines were accused of using algorithm manipulation to gain more user traffic.

Of course, there were many more significant differences between the two cases.

First, the levels of the relevant markets were different. While Google was found to hold dominance in the general search market (AT.39740, paras 154-190 and paras 271-330) and was accused of leveraging its position into the market for comparison shopping services (AT.39740, paras 191-263), NAVER was blamed to abuse its dominance in the market for the comparison shopping services (Decision No. 2021-027, paras 136-214 and paras 251-272) to increase its influence in the Korean e-commerce market (i.e., the market for “open market services”) (paras 215-245 and paras 109-411). [1]

Second, in the EU’s case, Google was obviously very dominant in the whole internal market. By contrast, in the Korean case, NAVER was, to my understanding, ‘just’ dominant, still facing a certain degree of competitive pressure from rivals, including Google. Even if one follows the KFTC’s argument, NAVER’s market share remained only circa 70% in the relevant markets (para 251 and Figures 50, 51). Compared to the market position of Google in Europe, called “superdominant” by the General Court, NAVER’s market position in Korea was clearly far from enough to be criticized for that position as such.

Third, there was a notable difference in the actual outcomes of the practices in question. While in Google Shopping it was revealed that Google’s rival services were excluded from the comparison shopping market due to the conduct in the Union, the situation in Korea was the opposite. The actual impact of the conduct in question on the Korean e-commerce market was unclear, and the causality between the conduct and the purported effects was questionable in NAVER Shopping (see Kim & Song 2021, Kang & Lim 2021, and Kim, 2022).

Fourth, as opposed to the European Commission, the KFTC relied not only on the abuse of dominance provision but also invoked some provisions for prohibiting unfair trading practices, i.e., unfair discrimination (Art. 45(1)(2), MRFTA) and unfair inducement (Art. 45(1)(4), MRFTA) (see the basic structure of the MRFTA). This might have been particularly helpful in justifying the agency’s findings before the appellant court, despite the lack of actual effects.

Seoul High Court’s Confirmation: “Yes, it’s abuse”

The KFTC’s decision was appealed to the Seoul High Court, which ruled on December 14, 2022, one year after the General Court’s Google decision (T-612/17). In its judgment numbered “2021Nu36129“, the Seoul High Court, as the General Court did, nodded to the enforcer’s findings and confirmed that NAVER, as a dominant company in the comparison shopping market, abused its dominance through the self-preferential and discriminatory conduct in question, maliciously demoting competitors and favouring its own service, NAVER Smart Store, in the market for providing e-commerce services.

The full text of the court’s judgment has not yet been released as of February 6. So, for the moment, it is unknown what was disputed and what was not disputed before the Court. Only the summary of the case published by the Court conveys some notable points that the ruling seems to contain. It seems that the Court declared very clearly that the KFTC was correct to find that NAVER’s dominance could be abused in a different market where the company did not have dominance. In my opinion, such a statement is an undeniable confirmation of the acceptance of the leveraging theory. Also, the Seoul High Court paid attention to the end user’s expectation for optimal search results (in the view of ‘unfair trading practices’), in addition to the conduct’s capability of restraining competition (in light of ‘abuse of dominance’). It looks like the Court recognized the fraudulent nature of the conduct in question (i.e., altering some parameters used to decide rankings in search results without informing users). I think this part may be worth comparing with the General Court’s decision (see Christian Bergqvist’s presentation).

NAVER Shopping, Enshrined in the Platform Guidelines

I believe that the Seoul High Court’s ruling has given much confidence to the KFTC. Indeed, one month after the Court’s decision, on January 12, 2023, the KFTC promulgated the final version of its Guidelines for Review of Abuse of Dominance by Online Platform Operators (entered into force on the same date), declaring that self-preferencing can be an abuse under the MRFTA (Platform Guidelines, III, 2. C. (1)-(5)).

According to the Platform Guidelines, self-preferencing, as opposed to the restrictions on multi-homing or the imposition of parity clauses taking place in one market, is construed as an exclusionary strategy that one takes to leverage his dominance in a different market other than the one he already dominates (III. 1). Specifically, self-preferencing is defined as a practice by which an online platform operator treats its own products or services, whether directly or indirectly, more favourably than others (sold by competitors) on its own platform (III. 2. C. (1)).

The KFTC warns that such conduct may cause competition concerns, especially where a vertically integrated platform operator abuses its dual role as both a marketplace and a competitor to merchants selling products or services on its platform by leveraging its market power in the connected market where it has no dominance and further strengthening its existing power as a platform operator (III. 2. C. (2)).

Of course, the KFTC does not reject the possibility of efficiency gains accompanied by self-preferential treatments, such as increasing convenience and improving user experience (III. 2. C. (3) and II. 3. C. (3)). The KFTC clearly says that the anti-competitive effects of self-preferencing will be weighed against the efficiency-enhancing effects. It should be noted, however, that the efficiency gains must be the least restrictive and must be beneficial to the entire market economy beyond internal cost-efficiency, according to the Platform Guidelines. In addition, it should be highly likely that such effects are generated by the conduct in question (II. 3. C. (1)).

The Platform Guidelines outlined the non-exhaustive list of factors to be considered when assessing the illegality of self-preferencing as follows: (A) the intention and purpose; (B) the duration of the accused conduct and the characteristics of the relevant products; (C) the method used for the accused self-preferential treatment; (D) the enhanced accessibility created by the accused conduct; (E) the relevant information disclosed to users; (F) the perpetrator’s market position in the dominating market and (G) another non-dominating market; (H) the relevant markets’ entry barriers; (I) the conduct’s effects on diversity and innovation and (J) upon consumer welfare.

What to Come in 2023?

The Platform Guidelines came into effect on the same date as the published date and it is already being used and applied to the ongoing self-preferencing case before the KFTC, Kakao Mobility.

Kakao Mobility is a ride-hailing service provider, operating a mobile app that connects taxi drivers and passengers in Korea. Reportedly, the KFTC alleges that the firm has abused its dominance in the mobile ride-hailing market to take the adjacent taxi franchise market by giving some advantages to taxi drivers subscribing to Kakao Blue, Kakao’s taxi franchise while discriminating against non-subscribers when allocating ride-calls. If the KFTC finally rules that Kakao Mobility has infringed the MRFTA by the self-preferential practice, this ruling will be the second self-preferencing case since NAVER Shopping in Korea.

Looking at the developments of the Kakao Mobility case, it seems that the KFTC has gained considerable confidence in tackling self-preferencing since the Seoul High Court’s decision. However, I still doubt whether such confidence can be justified by the NAVER Shopping decision. In my view, there are still several important questions that remain unanswered regarding the self-preferencing theory of harm. Among other things, does this practice really go beyond the scope of competition on the merits under the MRFTA? Should a vertically integrated dominant platform (especially when it offers a search service) be obliged to treat competitors on an equal basis? Should the MRFTA be considered to protect less efficient competitors than the dominant company? What is the role of counterfactuals in the competition assessment under the MRFTA? I hope these questions will be addressed by academia with the release of the court’s ruling in 2023.

_____________

[1] To speak more specifically, in NAVER Shopping, the Korean search engine was accused of discriminating against general sellers (registered at other competing platforms), giving preferential treatment to specific sellers subscribing to NAVER’s Smart Store service in search results (para 273 et seq). The KFTC argued that, thereby, NAVER was capable of leveraging its dominance in the market for comparison services to the market for open market services (the KFTC’s decision, para 302 et seq).

* The author thanks Jinha Yoon for having a useful discussion on the NAVER Shopping case.