Ignore the Debate Over Whether the Inflation Reduction Act Raises Taxes on Those Making $400,000 Or Less

As Congress is about to pass the Inflation Reduction Act, Washington is once again having a breathless debate over very little. This one is about whether Democrats are violating President Biden’s pledge to not raise taxes on households making $400,000 or less annually. But here’s the secret: This is yet another ridiculous political argument.

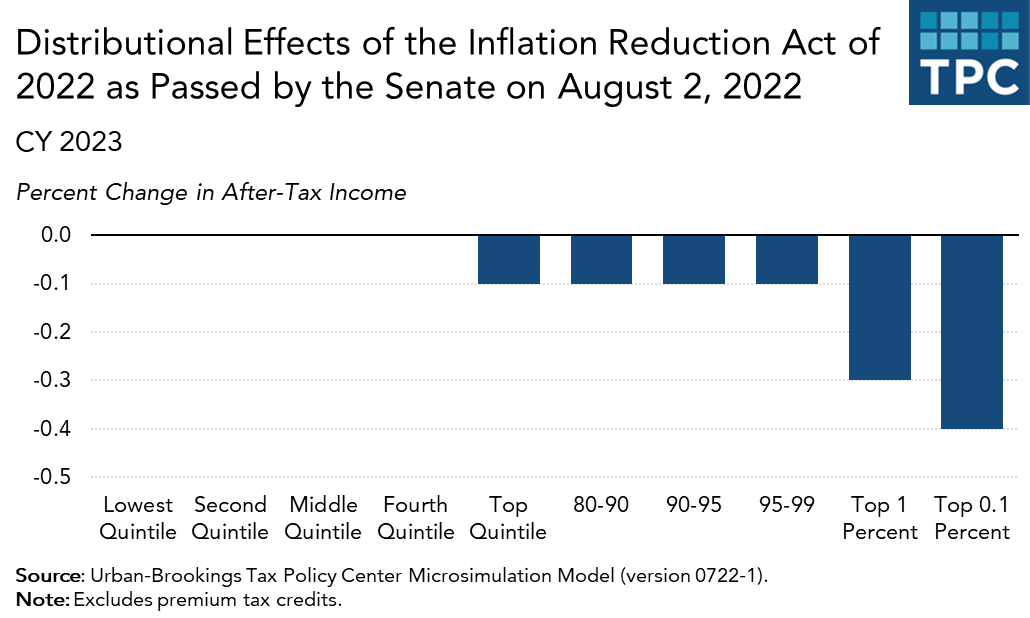

The Tax Policy Center analyzed the big climate, health, and tax bill three different ways. The bill is quite progressive every time. On average, the after-tax incomes of low- and moderate-income households either would go up a bit or not change in any measurable way. The average after-tax incomes of high-income people would decline. But on average, the vast majority of households will barely notice any tax change, one way or the other.

Effectively zero tax change

In one TPC analysis, average taxes of middle-income households would fall by $100. In another, they’d go up $20. But as a share of after-tax income, the change effectively is zero. And, in reality, nobody’s analysis is so accurate that there is any meaningful difference between estimates of a tax increase of $20 and a tax cut of $100.

Of course, that sign makes all the difference to politicians. A tax increase on those making $400,000 or less, no matter how tiny, gives Republicans the opportunity to accuse Biden and the Democrats of violating their pledge. And a tax cut, no matter how miniscule, opens the door for Democrats to gloat about how they’ve cut taxes for hard-working Americans.

Ignore them all.

To understand what’s really happening, think about what is in the bill. With the exception of a few pass-through business owners who claim large losses on their Form 1040s, nobody would pay more in federal individual income tax, no matter what their income. And that provision won’t even take effect until 2027.

There are no other individual income tax increases at all. President Biden once proposed a bunch of them, but Congress isn’t approving any this week.

Tax changes

There are two big tax increases on corporations. One is a minimum tax on the financial statement income of a few very large companies that currently pay little or no corporate income tax. The other is a tax on companies that buy back stock from their shareholders.

There also are about two dozen energy-related tax credits. And the bill temporarily extends a generous tax credit that subsidizes the premiums many low- and moderate-income people pay when they buy health insurance on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchanges.

Keep in mind that the distributional effects of the tax provisions of this bill are especially difficult to measure because the tax changes are so idiosyncratic.

Its highly targeted tax changes depend entirely on a taxpayer’s behavior. For example, if you buy an electric vehicle, you benefit from the bill’s tax credit of up to $7,500. But if you don’t purchase an EV, you get no tax benefit from the credit.

Similarly, some low-income households will get a big tax subsidy to buy private health insurance on the ACA exchange. Others with the same incomes may get health insurance through Medicaid or their work. They won’t benefit at all from the ACA premium subsidy.

Who pays the corporate tax?

It is the same story, though slightly more complicated, with the corporate minimum tax. TPC, the Joint Committee on Taxation, and other modelers assume that the corporate tax ultimately is paid by workers, shareholders, and other owners of capital. Workers don’t pay higher corporate taxes directly but receive less in compensation than they otherwise would. Shareholders would see the value of their investment drop if they held stock in one of the few dozen companies subject to the book minimum tax. Someone with exactly the same income and family size but with investments in companies exempt from the new tax may see no economic effect at all.

All this makes it impossible to calculate winners and losers within each income group. But TPC can show average tax changes for different income groups. My colleague John Buhl describes them in detail here.

But here are a few examples: Including the effects of the premium tax credit, middle-income households—those making between about $60,000 and $106,000—would get an average tax cut of about $100 in 2023. Excluding the premium tax credit, they’d get an average tax increase of about $20.

TPC doesn’t break out incomes at $400,000 but it does include a group making between about $280,000 and $409,000 (those in the 90th to 95th income percentiles). They would pay an average of about $180 more in tax, roughly enough for couple in that crowd to buy dinner at their favorite restaurant.

Next time you hear a politician pontificating about the big tax increases—or tax cuts—in this bill, pay no attention. They hope you don’t get the joke. But now you do.