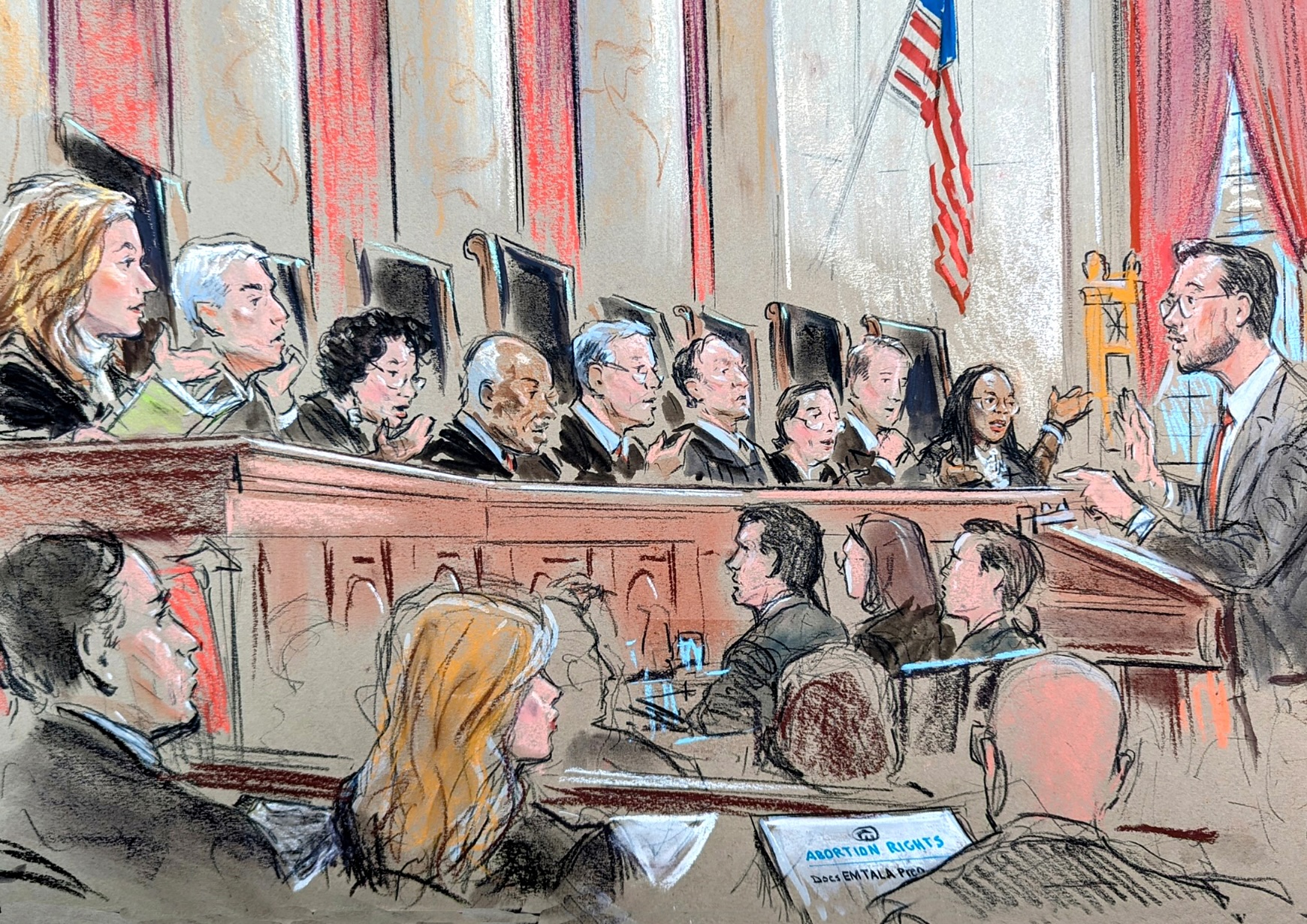

Supreme Court split on Texas age verification law for porn websites

ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

The Supreme Court was divided on Wednesday over a challenge against a Texas law requiring pornography websites to verify the user’s age before providing access. The state was allowed to enforce the law by a federal appeals judge in New Orleans last year, stating that the law was rationally related to government’s desire to prevent young people from viewing adult porn. Some justices appeared to agree with the challengers led by a group representing the adult entertainment industry that a federal appellate court in New Orleans had to apply a more rigorous test to determine if the law violated the First Amendment. Even that ruling may prove to be a limited win for the challengers. 1181. A federal judge in Austin (Texas) issued an order shortly after H.B. The state was temporarily barred from enforcing the law until 2023, when H.B. Senior U.S. District Judge David Alan Ezra concluded that the law is likely unconstitutional.

But the 5th Circuit lifted Ezra’s order, clearing the way for the state to implement the age-verification requirement. The court of appeals used a less rigorous standard, called rational-basis reviews, than Ezra. The strict scrutiny standard of review requires the government to show that the law serves a compelling government interest and is narrowly drawn to advance that interest. By contrast, the more rigorous standard of review, known as strict scrutiny, requires the government to show that the law serves a compelling government interest and is narrowly drawn to advance that interest.

Representing the challengers, Derek Shaffer told the justices that the 5th Circuit’s decision to apply rational-basis review was an “aberrant holding” that defies the Supreme Court’s “consistent precedents,” including the Supreme Court’s 2004 decision in Ashcroft v. ACLU, in which the justices applied strict scrutiny and concluded that a federal law – the Child Online Protection Act – similar to H.B. 1181 was likely unconstitutional.

Brian Fletcher, the principal deputy solicitor general who argued on behalf of the Biden administration, agreed with Shaffer that the court of appeals was wrong when it applied the less rigorous standard of review. But that should not prevent Congress or the states from preventing the distribution of pornography to children online, Fletcher emphasized.

Defending the law, Texas solicitor general Aaron Nielson stressed that the challengers do not dispute that the websites that H.B. 1181 targets harm children. If strict scrutiny was applied to H.B. Nielson told them that Texas would need to meet the same high standards to prevent children from entering strip bars. This is something that the Supreme Court cases do not require. Texas has been using content-filtering software for years, which is what the challengers claim as an alternative to H.B. The Supreme Court has in the past imposed strict scrutiny on laws that regulate adults’ access sexually explicit material. However, the Chief Justice John Roberts, and Justice Clarence Thomas, suggested that technological advances might warrant a re-examination of the standard. Access to pornography, Roberts observed has “exploded”: Not only is it much easier for teenagers to get access to porn, but the kind of porn that they can access has changed as well, becoming much more graphic.

Thomas noted that when the court issued its decision in Ashcroft, it was in a “world of dial-up Internet” access. “You’d admit that we are in an entirely new world,” he said.

Shaffer rejected the idea that technological advances justified a change in standard of review. While acknowledging that the government has a compelling interest in preventing young people from gaining access to porn – the first part of the strict scrutiny test – he stressed that technological advances would merely be something to consider as part of the determination whether strict scrutiny is satisfied.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, one of the justices on the court with teenaged children, also addressed the issue of technology and in particular the effectiveness of content-filtering software. She pointed out that it has “been 20 years” since the court’s ruling in Ashcroft, and that young people can now “get online porn through gaming systems, tablets.” “I can say from personal experience,” she told Shaffer ruefully, that content-filtering software for different systems that children can use to access the internet “is difficult to keep up with.”

Justice Samuel Alito echoed Barrett’s concerns, asking Shaffer whether he knows “a lot of parents who are more tech savvy than their 15-year-old children”? “There’s a huge volume of evidence,” Alito maintained, “that filtering doesn’t work.” Why, he queried, would so many states – 19 in total – have adopted age-verification requirements “if the filtering is so good?”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson countered that advances in technology would in any event “cut

both ways”: Although such advances would increase young people’s access to technology and make porn more ubiquitous, she said, it also increases the burdens on adults who want to view porn online because of the greater likelihood that their privacy will be infringed.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that she believed that many of her colleagues’ questions actually addressed the question of whether H.B. The question is not whether H.B. 1181 can be reviewed under strict scrutiny but rather what standard should be used. In her view, the answer to the latter question was a straightforward one, based on the Supreme Court’s cases: strict scrutiny.

Jackson agreed, emphasizing that Ginsberg – the case on which the court of appeals relied – was a case that dealt with the rights of young people, rather than the rights of adults.

Shaffer agreed. He told the justices that Ginsberg addressed only the rights of minors and did not impose an across-the-board age-verification requirement.

But even if the justices ultimately agree that the court of appeals applied the wrong standard, the law could remain in effect for the foreseeable future. The challengers asked the Supreme Court to rule that the 5th Circuit failed to apply strict scrutiny, and that the law does not pass that test. However, it was possible that they could ignore that second question and send the case back to be re-examined. In that case, Ezra’s order blocking the law could remain on hold while proceedings continue, allowing Texas to continue enforcement.

A decision in the case is expected by late June or early July.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court. []