Supreme Court is ready to uphold Tennessee’s ban on transgender youth care

ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Dec 4, 2024

at 4:06 pm

U.S. (William Hennessy)

This article was updated on Dec. 4 at 4:43 p.m. (William Hennessy)

This article was updated on Dec. 4 at 4:43 p.m.

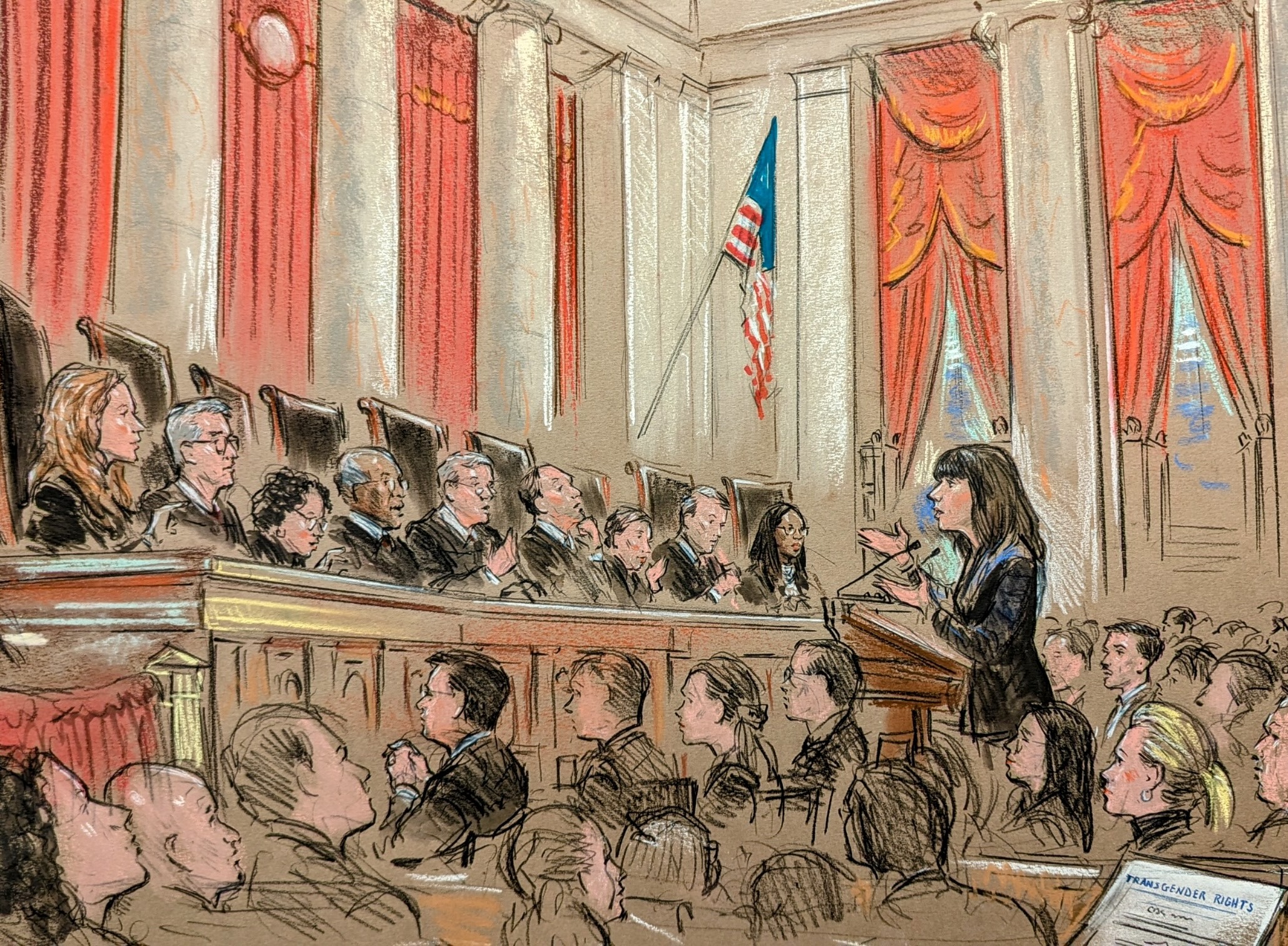

During almost two-and-a-half hours of debate on Wednesday, nearly all of the court’s conservative majority expressed skepticism about a challenge to Tennessee’s ban on puberty blockers and hormone therapy for transgender teenagers. Three transgender teenagers, their families and a Memphis doctor, along with the Biden Administration, claim that the law violates equal protection guarantees in the Constitution and should be examined at the highest level of legal scrutiny. Tennessee counters by stating that it is exercising its right to regulate the practice medicine for all youths and does not make a distinction based on the sex of a patient. This idea has been a recurring theme on the court over the past few years, and was even used in the landmark decision of 2022 that overturned the constitutional right to an abortion. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, in particular, asked aloud on Wednesday whether decisions like gender-affirming treatment for transgender teens should be left to democratic processes. Elizabeth Prelogar, the Solicitor General, urged the Justices to focus their attention on the narrow issue of whether the Tennessee law SB1 draws distinctions on the basis of sex, and therefore should be subjected to a more rigorous review than that applied by the federal appeals court in Cincinnati which upheld the law. But although the court’s three Democratic-appointed justices clearly agreed with her, it was difficult to say whether there were two more votes to join them and send the case back to that court for another look.

Representing the Biden administration, Prelogar emphasized that SB1 singles out gender dysphoria as the sole basis to ban access to puberty blockers and hormone therapy, because young people who are not transgender can still have access to those drugs for other medical purposes. She explained that SB1 draws lines based solely on sex because it only prohibits access to these drugs when they are used in a way that is inconsistent with a young person’s assigned sex at birth. She argued that it should be subjected to a heightened level of scrutiny rather than the deferential rational basis review used by the U.S. Court of Appeals of the 6th Circuit to uphold the law. Justice Sonia Sotomayor explained to Tennessee’s solicitor-general, J. Matthew Rice that the law is based on sex in determining who gets medicine. Sotomayor said that a doctor must know if a child, who appears to be gender-neutral, is male or female before he can determine if SB1 prohibits the use drugs. Justice Elena Kagan, however, was sceptical and told Rice that SB1 is intended to ban the treatment of gender dysphoria. She said that pointing to a medical purpose is “a dodge”, when the medical purpose for SB1 “is utterly, and entirely, about sex.” He said that this case involves “a different type of inquiry” due to the need to review “evolving medical standards.” “We’re not the best situated to address issues like that,” he posited, suggesting that such determinations such instead be left to the legislature.

Prelogar countered that although states have leeway to regulate the practice of medicine, heightened scrutiny should apply when states regulate access to medicine based on a patient’s birth sex. It would “be a pretty remarkable thing,” she said, to say that heightened scrutiny wouldn’t apply in areas of medical regulations.

Justice Samuel Alito observed that medical groups in European countries have more recently been skeptical of the benefits of gender-affirming care for trans teens.

Prelogar pushed back, noting that countries like Sweden, Finland, and Norway had not changed their laws in light of those reports but instead called for more individualized approaches to gender-affirming care. Similarly, she added, there is no outright ban on the use of hormone therapy and puberty blockers in the United Kingdom.

Kavanaugh told Prelogar that she had presented “forceful policy arguments,” but that Tennessee and other states with similar laws had also advanced forceful arguments. If the “Constitution doesn’t take sides on how to resolve medical and policy arguments,” he said, why shouldn’t the courts leave these kinds of questions to the democratic process?

Prelogar reiterated that the Biden administration was not asking the Supreme Court “to take options away from the states.” The court could, she assured Kavanaugh, write a “very narrow” opinion holding only that when a state prohibits conduct based on sex, heightened scrutiny applies. The court could then send the case back to the 6th Circuit for another look using that more stringent standard, which would require the state to show that the law is substantially related to an important government interest.

Sotomayor was more skeptical about the ceding the issue to the democratic process. Rice asked Rice if a ruling in Tennessee’s favor would allow states to block gender affirming care for adults. She noted that transgender people only make up 1% of the general population. It’s “very hard to see how the democratic process” will protect them, she contended, just as it didn’t protect women or people of color for a long time.

Kavanaugh also wanted to know what a decision indicating that heightened scrutiny applies to SB1 would mean for issues like transgender women in sports and efforts to regulate bathrooms.

Prelogar distinguished the dispute over SB1 from those cases, emphasizing that allowing transgender teens to access medicine “in no way affects the rights of other people.” The Supreme Court, she suggested, could indicate that its ruling does not affect the separate government interest in those cases.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett focused on suggestions that heightened scrutiny is appropriate because SB1 discriminates based on transgender status. She pressed both Prelogar and Chase Strangio, representing the families and who on Wednesday became the first openly transgender lawyer to argue before the court, on whether there is a long history of legal discrimination against transgender people.

Prelogar indicated that even if there was no history of laws discriminating against transgender people, there is a “wealth of evidence” of other kinds of discrimination against them. Strangio pointed to earlier bans on service by transgender people in the military, as well as bans on cross-dressing.

Barrett also emphasized that the court’s resolution of the case would not affect the separate question (which the court declined to review) of whether SB1 violates the fundamental rights of parents to make decisions about their children’s medical care.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson drew questioning back to the fundamental role of the court’s authority on equal protection, invoking Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court’s 1967 case striking down Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage. She said that in the 1967 case of Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court struck down Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage, a person’s ability to marry depended on their race, even though it was illegal for everyone. Here, access to puberty blocking drugs is based on a patient’s assigned sex at birth. She said that Virginia also used scientific arguments to defend its ban on interracial weddings, and that the court should give the legislature the final say. If the court declines to hold that SB1 should be subject to heightened scrutiny, she said, it would be ignoring “bedrock precedent.”

Prelogar stressed that even if the courts apply heightened scrutiny to laws like SB1, it still leaves “real space” for states to regulate. She pointed to West Virginia’s law regulating gender-affirming care for trans teens, which she described as imposing “precisely tailored guardrails” – for example, requiring two doctors to diagnose gender dysphoria along with a mental health screening and consent from both parents and the patient’s primary-care physician.

Alito countered that even with such guardrails, applying heightened scrutiny would require “lay judges” to make “complicated medical” decisions that would lead to “endless litigation.”

Strangio stressed that the West Virginia law had not faced any challenges, but – particularly with Justice Neil Gorsuch silent throughout the argument – a majority of the justices were not persuaded.

A decision in the case is expected by summer.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.