The DMA and Gatekeeper Power: Keeping Generative AI in check

One of the most popular developments is services that rely on natural language processing (NLP) in the form of chatbots. In a previous post, I discussed the opportunities that the Digital Markets Act provides the regulator in order to expand the list of core platform service (CPS) so as to include generative AI. In response to the initial discussion and thought sparked by that article, I began reflecting on the dimensions of interplay between generative AI, and DMA.

As such, I wrote a working paper

which presented three distinct scenarios for how generative AI could be interpreted within the context of regulation. The European Commission could use two tools in addition to the obvious inclusion of generative AI into the list of CPSs: i) applying the existing obligations to the functionalities of CPSs that rely on generative AI, and ii), designating additional services from the current list of CPSs. The underlying technology and the scope of the risks posed by it

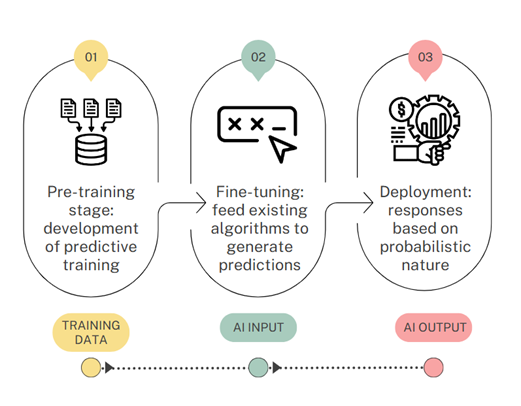

Generative AI is a broad topic. They ‘generate,’ that is, novel outputs in text, images, or other formats, based on the user’s prompt. LLMs are a type of generative AI that is text-based. The easiest way to depict them is to break down a generative model’s technical development into three stages as Figure 1 below: pre-training, fine-tuning and deployment.Figure 1. The three stages in the development of generative AI systems

They rely on data for pre-training. Generative models are fed by huge amounts of unstructured textual information. The model (the “M” in LLM) gains a lot of general knowledge by reading books, websites and articles. The model is able to capture the nuances of syntax, grammar and semantics in order to be able to predict, at the deployment phase, the most likely combination of words that it should generate as a response to a given prompt. This pre-training phase could be a bottleneck for the market, as accessing data is expensive and limited. The fixed costs are high, while marginal costs are low. A massive collection of data can have grave consequences for privacy and data protection. The lack of transparency in relation to the data types and sources that AI deployers have access to to perform the task is the most obvious consequence at the pre-training stage. Aside from that, substantial compute and energy cost goes into training LLMs.

Pre-training continues until the model achieves satisfactory performance on the task. The model is pre-trained until it achieves satisfactory performance on the task. Pre-trained models may have a good understanding of language but are not specialised to perform any specialised tasks. The fine-tuning stage is exactly what’s needed. The fine-tuning of input data (smaller datasets) containing specific examples stored within smaller domain-specific datasets will enhance the performance of the model on specific tasks. The deployment stage is when the deployers start to customize the inferences that they want to display. Due to the complexity and size of the data used in training, the designers of these models have limited control over the conclusions that are generated. The very nature of self-learning AI operates with unknown variables and autonomous inferences, which oppose the data protection principles of both transparency and purpose limitation.

Once both pre-training and fine-tuning are completed, deployment does not necessarily entail launching the service into the market. Deployers must take precautions to ensure that their LLMs are cost-effective when they launch them into production. Distribution can be done via a standalone app (e.g. ChatGPT), or by integrating it into existing apps and services (e.g. Apple’s release Apple Intelligence in its devices). The generative model produces a single synthesised response in response to a question. Capturing generative artificial intelligence under the DMA, and not adding a new CPS.

Capturing AI generative under the DMA.

The most obvious policy to capture AI generative under the DMA would be to add a CPS under Article 2(2). This is the idea of generative AI being viewed as a separate service, distinct from other CPS categories. Both the High-Level Group DMA

and European Parliament

have suggested this idea as an alternative to the DMA’s regulatory caps. In my previous blog post, I explained that the legislative reform needed to make this incorporation possible would require, at a minimum, a 12-month investigation of the market, followed by a legislative proposition drafted by the European Commission. This legislative proposal would be sent to the European Parliament, and then the Council. The EU institutions would then decide whether such an amendment should be included in the DMA’s current legal text.

Generative AI as embedded functionality

Let’s say that we wish to speed things up. The European Commission has already designated 24 core platform services to seven gatekeepers. The High-Level Group has pointed out that generative AI functionality has already filtered into the DMA’s scope of application, to the extent where gatekeepers have integrated AI systems into their CPSs. Aside from their proprietary foundation models, gatekeepers such as Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta and Microsoft have integrated generative AI-driven functionality into their existing products.

Functionality has been made available directly to the gatekeeper’s services. Google Search, for example, offers beta access to its Search Generative Experience in the US where generative AI is integrated with its legacy service. Article 6(5) DMA’s prohibition on self-preferencing does not only apply to online search engine. Ranking in the sense of Article 2(22) DMA refers to the relative prominence given to goods or services or search results offered through social networks, virtual assistants, search engines, or online intermediation services. Ranking in the sense Article 2(22) DMA is the relative importance given to goods, services, or search results through social networks, virtual assistances, search engines, or online intermediary services. In the traditional sense of ranking, it is based on the back-end functions, indexing and crawling. This relies on an algorithm. The integration of generative AI in ranking involves the transformation of an online experience. The interface of Google Search results has changed. The top of the page displays a single answer. The transparency, fairness, and non-discriminatory requirements that must be met by ranking in accordance with Article 6(5) DMA will impact the “enhanced” versions of these services that are powered by generative AI. The DMA’s enforcer must carefully determine what transparency means within the context of the regulation. Instead of adding a CPS to the existing list in Article 2(2), three categories of CPSs may capture the phenomenon (cloud computing services, virtual assistants and online search engines).

Cloud computing services are digital services enabling access to a scalable and elastic pool of shareable computing resources. Cloud computing services are the top layer in the AI stack. Cloud computing providers are facing a computing power shortage. Cloud computing is an alternative to accessing computing, since hardware-based GPUs are largely in the hands of a single company (i.e. NVIDIA). Cloud infrastructure firms like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud and Microsoft Azure, are the main players in the market. They have raised concerns to competition authorities about the market’s concentration. The EC’s potential designation would only address access to computing power, not generative models. At the outset, designating a gatekeeper for its cloud computing services does not add much to the generally applicable framework to the regulatory target, since no DMA provision is particularly tailored to address the concerns arising from that market.

Moreover, both virtual assistants and online search engines bear the nature of ‘qualified’ CPSs in the DMA, given that several mandates only apply to them, to the exclusion of any other CPS category.

For the online search engine CPS category, Articles 6(11) and 6(12) specifically address the need for the gatekeepers to provide access, on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms, to two distinct tenets of its services. Article 6(11), for example, mandates that gatekeepers provide access to their ranking, query, view and click data. Article 6(12), however, imposes the same type of access in order to benefit business users. Chatbots, and the forms that they take at the downstream level to search for information, could be considered CPS services. The main characteristic of the definition is that it intermediates queries (end users) with results (indexed results of business users). The definition’s main characteristic is that of intermediating queries (end users) with results (indexed results of business users).

Examples such as Perplexity’s service evidence that the deployment of generative models may result in equivalent services to those of online search engines in the sense of the DMA. Perplexity is not the same as Google Search. The main difference is that Google Search summarises the results of a search and then provides source citations in its response. Perplexity, on the other hand, simply lists the most relevant results. Perplexity also uses previous search queries to personalise future results. These features do not affect the chatbot’s main purpose, which is to provide accurate indexed search results based on a user’s prompt. In the case of virtual assistants across the board, industry players integrate ChatGPT plug-ins into their services to allow consumers to have a conversational interaction while the generative model performs simple tasks on their devices. Article 2(12), defines virtual assistants to be software that processes demands, tasks, or questions based on audiovisual, written input, gestures, or motions. Based on these demands, tasks, or questions it provides access to other controls or services connected to physical devices. The last phrase in the definition (‘provides control or access to other services connected physical devices’), suggests that the legislator wasn’t thinking about chatbots, but the interconnectedness of Big Tech virtual assistants with IoT devices. Chatbots that act as virtual assistants are not yet considered virtual assistants under the DMA, because they do not have the required impact on the physicality of the user. Often, these challenges are worth capturing through existing regulations. The DMA isn’t a piece of legislation that is incomprehensible and does not allow other legal options if they aren’t directly contemplated by the letter of law. The interpretation of the DMA is permeable, given the technical developments in the field. Such an approach allows for the application of a wide range of DMA provisions to the particular needs of generative AI, namely the principles of transparency and fairness.

Likewise, those enforcement priorities may entail the triggering of additional CPS designations with respect to deployers of generative AI systems seeking to enter the markets of existing CPS categories, namely search engines or virtual assistants. According to the principle of technology neutrality, generative AI can be regarded as an underlying technology for existing Internet functionalities, despite their technical complexity and particular nuances. As opposed to the first scenario, this perspective accommodates the current provisions to moderate gatekeeper behaviour stemming from non-designated undertakings.To the European Parliament’s and Commission’s call to capture generative AI via the DMA, I would recommend applying a more intensive interpretative exercise on the regulation’s provisions. This approach could be more effective and targeted at addressing the few obvious contestability and fairness issues arising from lack of transparency in generative models.