Responding to the Chamber of Commerce and the Economic Policy Institute

The Chamber of Commerce has its stable of high-immigration talking points — telling us, for example, that the official unemployment rate is low, that immigrants are “filling gaps” and boosting GDP, and that enforcing immigration law would be “draconian”.

This week, however, the purveyor of those same tropes is the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented think tank whose scholars once had a more nuanced view of immigration and its impact on workers and the country. We live in strange political times, when it seems that nearly everyone on the left endorses high immigration without a hint of reservation. In any case, the EPI post, written by Daniel Costa and Heidi Shierholz, criticizes my recent report comparing immigrant and native job growth, so I want to make a few points in response.

First, Costa and Shierholz’s assertion that immigration has no impact on labor market outcomes for U.S.-born workers is simply wrong. The 2017 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine study of immigration lists numerous studies showing negative wage impacts, especially on the less-educated. A 2019 review of over 50 studies by Anthony Edo in the Journal of Economic Surveys comes to similar conclusions. But we need not rely solely on academics. Business groups like the Chamber of Commerce have openly pushed for more immigration in order to slow the inflation supposedly caused by high wages. In fact, inflation has led immigration advocates over the last couple of years to argue not only that immigration holds down wages, but it’s good that it does!

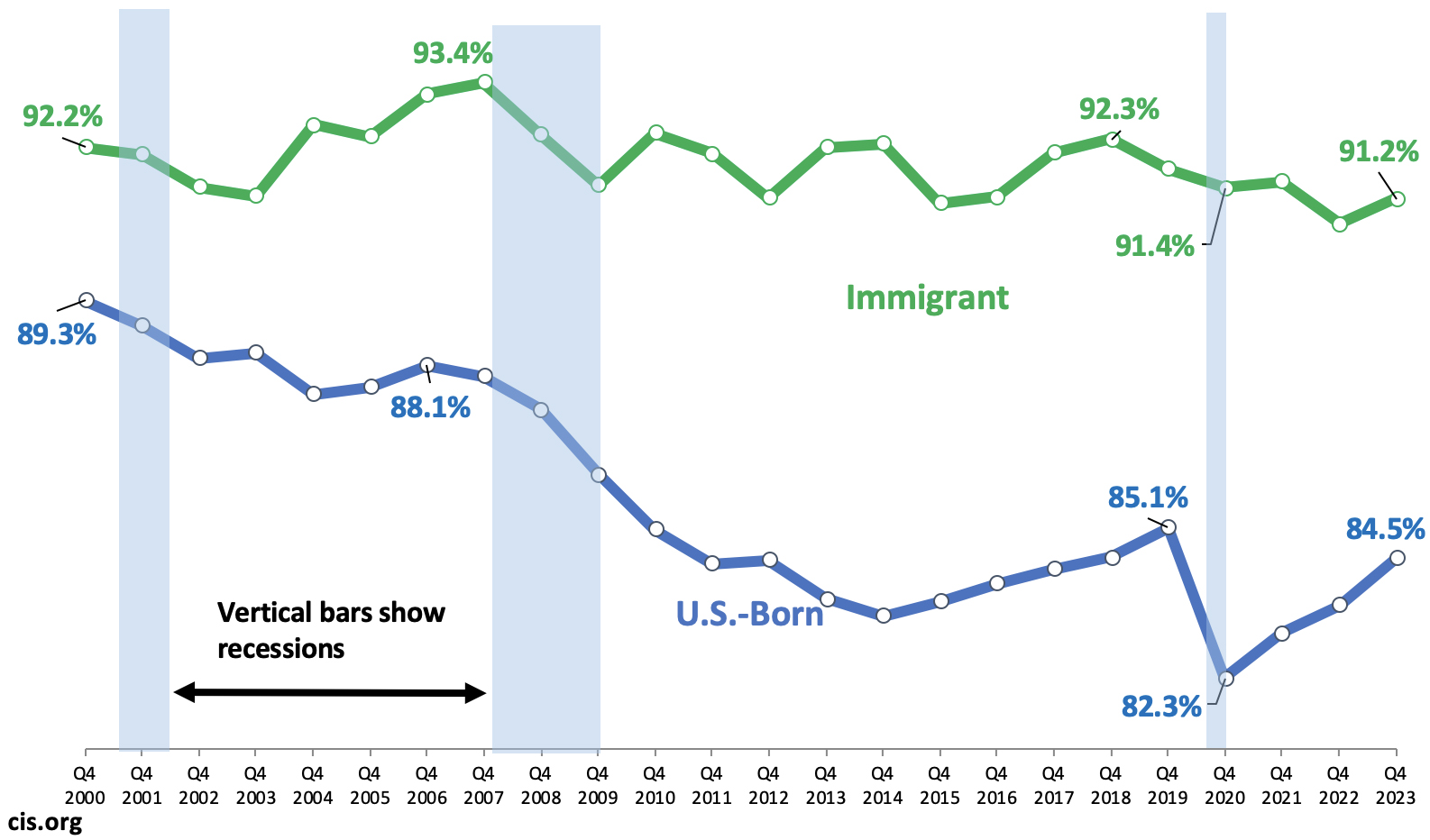

Second, the EPI authors’ argument that the labor force participation rate for “prime-age” U.S.-born men (25 to 54) has improved since the low of 2020 is not reassuring. The figure below comes directly from our recent employment report and shows the labor force participation of prime-age U.S.-born men. The rate for these men has certainly improved since the depths of Covid, but it remains below the level of 2019 and is well below the prior peaks in 2006 and 2000. In fact, participation has been declining for these men going back to 1960, when more than 90 percent were in the labor force. The recent increases, while encouraging, in no way to fix this very longstanding problem.

Labor Force Participation for Immigrants and U.S.-Born Men (Ages 25 to 54) Without a Bachelor’s Degree, 2000 to 2023 |

| Source: Center for Immigration Studies analysis of the Current Population Survey public-use files for every year from the fourth quarter of 2000 to the fourth quarter of 2023. All figures are seasonally unadjusted and are for non-institutionalized civilians, which does not include those in institutions such as prisons and nursing homes. “Immigrant” matches the Census Bureau’s definition of “foreign-born” and includes all persons who were not U.S. citizens at birth. Those in the labor force are working or looking for work. Figure excludes all those with a bachelor’s degree or higher. |

Equally important, to argue that immigration can reduce labor force participation or wages of natives is not the same as saying it is the only factor that ever matters, or that things can never improve for workers during a period of high immigration. To suggest, as Costa and Shierholz do, that the recent improvement in labor force participation for less-educated men means immigration has no impact on these workers makes no sense. Moreover, their assertion that the increase in labor force participation among less-educated men is “beating expectations” is persuasive only if one has very low expectations.

Third, is whether concern about immigration is really a “distraction from dynamics that are actually hurting working people”, such as weak labor standards and unions, as Costa and Shierholz allege. These “dynamics”, they write, have put “too much power in the hands of corporations and employers”. But increasing the supply of workers through immigration is exactly one of those dynamics. Why the particular dynamic of immigration no longer concerns the EPI authors is not clear, especially when one considers the history of the labor movement.

As the late Vernon Briggs, a strong supporter of unions, argued in his book, Immigration and American Unionism, “Unions thrive (membership grows) when immigration is low or levels are contracting; unions falter (membership declines) during periods when immigration is high or levels are increasing.” Briggs adds that union leaders for most of American history “intuitively believed this to be the case and acted accordingly”. Costa and Shierholz would do well to consider what labor leaders knew in decades past: Immigration is generally not in the interests of American workers. To be sure, immigration is by no means the only issue confronting American workers, but it should not be dismissed as a “distraction” when all of the evidence indicates otherwise.