Draft Guidance Puts March-In Authority Pursuant to Bayh-Dole in the News Once Again | Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati

On December 8, 2023, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released the Draft Interagency Guidance Framework for Considering the Exercise of March-In Rights (guidance) to the public for comment. The comment period ends February 6, 2024. The information received in response to the guidance will inform NIST and the Interagency Working Group for Bayh-Dole (IAWGBD) in developing a final framework document that may be used by an agency when deciding whether to exercise its march-in authority. While the guidance is the first federal framework specifying that price can be a factor in considering whether the government may exercise its march-in authority pursuant to 35 U.S.C. 200 et seq. (Bayh-Dole), this is not the first time that attention has been drawn to the government’s march-in authority.

Petitions were previously filed for the government to march-in over the high price of HIV drug Norvir/ritonavir (2004/2012), glaucoma treatment Xalantan/latanoprost (2004), Fabry disease treatment Fabrazyme/agalsidase beta (2010), and prostate cancer drug Xtandi/enzalutamide (2016). In each case, the petitioned agency found that march-in was not warranted. More specifically, the National Institutes of Health previously determined that the extraordinary remedy of march-in is not an appropriate means of controlling drug prices. This is in agreement with the named authors of Bayh-Dole, who have stated that Bayh-Dole was never meant to control drug prices. Therefore, while agencies have considered march-in in the past, no agency has exercised its rights. Consequently, even with adoption of the guidance, future petitioners for march-in on price alone are expected to struggle.

Bayh-Dole

The federal government invests billions of dollars each year in extramural research and development at universities, non-profits, and small and large businesses. Bayh-Dole was enacted to provide incentives to promote commercialization of federally funded inventions. Bayh-Dole allows recipients of federal research funding (contractors) to retain rights to inventions conceived or first actually reduced to practice under a federal funding agreement (subject invention), however, the government retains certain rights and imposes certain obligations on the contractors, including the authority to march-in. With march-in authority, an agency under whose funding agreement the subject invention was made can require a contractor, assignee or an exclusive licensee to grant a license to the subject invention in any field of use to a responsible applicant or applicants. If the contractor, assignee or exclusive licensee refuses, the agency may itself grant such a license.

March-In Determination

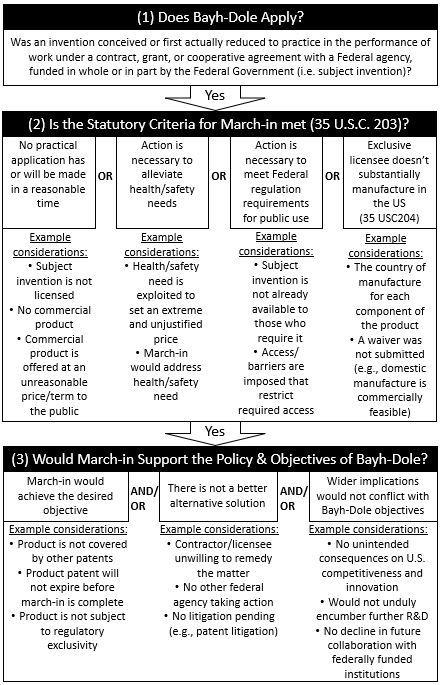

The specific statutory circumstances where an agency may march-in are enumerated in 35 U.S.C. 203. In view of the potential ramifications of exercising march-in authority, the guidance provides agencies a framework to ensure that any decision to march-in is consistent with the policy and objectives of Bayh-Dole. In this regard, the guidance provides three overarching questions that must be assessed when determining if march-in is appropriate:

- Whether Bayh-Dole applies to the invention(s) at issue?

- Whether any of the statutory criteria of 35 U.S.C. 203 for exercising march-in applies under the circumstances?

- Whether the exercise of march-in rights would support the policy and objectives of Bayh-Dole?

Each of the three overarching questions are evaluated in detail below in view of the guidance. A chart showing example considerations that may be evaluated when addressing each question is provided in Figure 1.

Does Bayh-Dole Apply?

An agency must first determine if Bayh-Dole applies to the invention in question. Specifically, was the invention conceived or first actually reduced to practice under a federal funding agreement. If no, the assessment ends as the government has no march-in authority pursuant to Bayh-Dole. If yes, the government will assess if the statutory criteria for exercising march-in is met.

Is the Statutory Criteria for March-In Met (35 U.S.C. 203)?

Importantly, an agency can only exercise march-in rights in four specific circumstances as enumerated in 35 U.S.C. 203. Each criterion will be addressed in turn below.

Criterion 1. Action is necessary because the contractor or assignee has not taken, or is not expected to take within a reasonable time, effective steps to achieve practical application of the subject invention in such field of use.

The first criterion addresses whether or not effective steps have been taken to achieve the practical application of the subject invention. Where a contractor or licensee has stopped work on a subject invention, has refused to restart work and rejects requests to license the subject inventions, such a situation could suggest limited opportunities to commercialize the subject invention into new products. Additionally, stalled product development could also be an indication of conflict with the objectives of Bayh-Dole, which include encouraging the utilization and commercialization of federally funded inventions.

The pricing of products may also satisfy criterion 1 if the price or other terms with which a product is being offered to the public conflicts with the objectives of Bayh-Dole. For example, where the price or other terms are not reasonable and therefore unreasonably limits availability of the invention to the public. While such an assessment will be fact intensive, criterion 1 may be satisfied where a contractor or licensee makes the product available only to a narrow set of consumers or customers because of high pricing or other extenuating factors with no justification. However, the facts would weigh against march-in where the entire market has seen similar price increases and there is a compelling justification for the high price.

Criterion 2. Action is necessary to alleviate health or safety needs which are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or their licensees.

The second criterion addresses whether march-in is necessary to alleviate health or safety needs. An agency may assess what it would take to better or fully meet the health or safety needs. Under criterion 2, agencies may evaluate how march-in could address the health or safety needs in view of the contractor’s or licensee’s action. For example, are contractors or licensees refusing to ramp up manufacturing and how much has price increased. Here, the facts would weigh in favor of march-in where a contractor or licensee is exploiting a health or safety need in order to set a product price that is extreme and unjustified given the totality of circumstances. This may be evidenced by a sudden implementation of a steep price increase in response to a disaster that is putting people’s health at risk.

Criterion 3. Action is necessary to meet requirements for public use specified by Federal regulations and such requirements are not reasonably satisfied by the contractor, assignee, or licensees.

Criterion 3 relates to whether federal regulations are met. More specifically, agencies will evaluate whether federal regulations relate to the use of products commercialized from the subject invention. In this regard, an agency will assess whether a contractor or licensee has taken reasonable steps to address any needs related to these federal regulations, including making the subject invention available to all who require it.

Criterion 4. Action is necessary because the agreement required by section 204 has not been obtained or waived or because a licensee of the exclusive right to use or sell any subject invention in the United States is in breach of its agreement obtained pursuant to section 204.

The fourth criterion relates to 35 U.S.C. 204 which requires that exclusive licenses to use or sell in the U.S. include an agreement that products embodying subject inventions be manufactured substantially in the U.S. The agency may evaluate and take into consideration the manufacturing locations of all components of the product to determine if the product can be considered to have been manufactured substantially in the U.S. Importantly, this requirement can be waived if there is a showing that reasonable but unsuccessful efforts have been made to grant licenses on similar terms to potential licensees that would be likely to manufacture substantially in the U.S., or that under the circumstances domestic manufacture is not commercially feasible.

In making a determination with regard to criterion 4, an agency will request specific details on where the subject product is manufactured and determine if a manufacturing waiver is required and if a request to waive the preference for U.S. industry has been granted.

Would March-In Support the Policy and Objectives of Bayh-Dole?

The final question set forth by the guidance relates to whether or not march-in would support the policy and objectives of Bayh-Dole. Bayh-Dole was enacted to incentivize U.S. innovation and promote access to these innovations in the U.S. As such, agencies should evaluate whether an individual march-in decision would advance or impede Bayh-Dole’s objectives. Agencies should also weigh how an individual march-in decision could impact the broader policy objectives for U.S. competitiveness and innovation. In this regard, the following inquiries may be assessed:

- Would march-in help achieve practical application, alleviate health or safety needs, meet public use requirements, or meet manufacturing requirements?

- Are there other ways to address the identified problem, and can those alternatives be pursued instead of or in parallel with any march-in proceedings?

- What are the wider implications of use of march-in?

Therefore, prior to exercising march-in, agencies are encouraged to consider the impact of such a decision on U.S. innovation and the commercialization of inventions that arise from federally funded research and development.

March-In Procedure

The guidance further summarizes the march-procedure set forth in 37 CFR 401.6. This procedure provides a forum where the contractor is permitted to submit information and arguments opposing the use of march-in. Where there is a genuine dispute over material facts upon which the march-in is based, the agency will undertake fact-finding where the contractor will be given the opportunity to submit arguments or, if requested, present oral arguments. Once a march-in decision is made, a contractor, inventor, assignee, or exclusive licensee adversely affected by a march-in decision may appeal that decision in the United States Court of Federal Claims.

Conclusion

The guidance provides a framework detailing prerequisites for exercising march-in in view of the policy and objectives of Bayh-Dole and instructs that march-in considerations are extremely fact-dependent, and any decision will be made based on the totality of all circumstances.

To date, no agency has exercised its march-in rights and very few, if any, therapeutic products are reliant solely on federally funded inventions. Even if the guidance is adopted and price is taken into consideration when evaluating whether to march-in, price will be one of many factors. These factors include, for example, the wider implications of a decision to march-in, and the decision’s potential impact on U.S. innovation and the commercialization of inventions that arise from federally funded research and development. As such, future petitioners for march-in on price alone are expected to face an uphill struggle.