After Jack Daniel’s, the Other Shoe Drops for MSCHF in Wavy Baby Trademark Case | Pillsbury – Internet & Social Media Law Blog

On December 5, 2023, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction secured by skateboard apparel company Vans against, MSCHF, an infamous parodist company. The Court found that the district court had correctly concluded that Vans was likely to succeed on its trademark infringement claims against MSCHF for its Wavy Baby sneakers, which allegedly parodied Vans’ iconic “Old Skool” sneaker design.

While the decision is a clear victory for Vans, its implications for parody goods are broader still. The Second Circuit’s ruling revisits Rogers v. Grimaldi, a nearly 35-year-old decision that crafted a First Amendment filtering test that has been widely adopted by federal courts. It also marks the first time that the Second Circuit has considered the Rogers test since the U.S. Supreme Court rejected its application in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, 599 U.S. 140 (2023). The result? Perhaps not surprisingly, a finding that the Rogers test does not apply.

Background and Lower Court Decision

MSCHF (pronounced “mischief”) is an American art and media company known for its creative and controversial products that criticize consumer culture, comment on society, and often go viral as pranks. In 2021, MSCHF released “Satan Shoes,” a sneaker collab with rap artist Lil Nas X that paired Nike-produced sneakers with satanic imagery and “60cc of ink and 1 drop of human blood” in each pair. Nike quickly filed a lawsuit, prompting settlement just months after the release.

One of MSCHF’s more recent drops—the Wavy Baby, a collab with rap artist Tyga—targeted well-known footwear and skateboard-friendly apparel company Vans and, specifically, its famed “Old Skool” shoe.

In April 2022, in anticipation of the drop of the Wavy Baby shoe, MSCHF collaborated with musical artist, Tyga, for a marketing campaign to garner hype for the sale. Upon learning of the upcoming drop, Vans sent MSCHF a cease-and-desist letter and filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York alleging six claims under state and federal law, including trademark infringement under the Lanham Act. Yet MSCHF continued with the planned drop and sold 4,306 Wavy Baby shoes through MSCHF’s proprietary app.

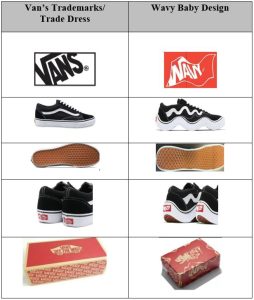

In the litigation, Vans asserted that MSCHF’s Wavy Baby product infringed Vans’ registered trade dress rights in various aspects of its Old Skool shoe design, including the perforated shoe sole, the heel logo, the side stripe, the black-and-white color scheme, the footbed logo and the packaging, (as shown below):

The district court issued a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction against MSCHF, finding that Vans would likely prevail on its trademark infringement claims. MSCHF appealed that decision to the Second Circuit.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s Bad Spaniels Decision

After Vans prevailed against MSCHF before the district court, but before the Second Circuit had rendered a decision on appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its decision in Jack Daniel’s Properties, Inc. v. VIP Products LLC, 599 U.S. 140 (2023). There, the Supreme Court found that a parody product—a dog toy shaped like a Jack Daniel’s bottle (below left)—infringed trade dress in the shape and design of the famous Jack Daniel’s whiskey bottle (below, right):

In doing so, the Supreme Court considered the test espoused by the Second Circuit in Rogers v. Grimaldi. There, the Second Circuit affirmed dismissal of Ginger Rogers’ Lanham Act false endorsement claim over a movie title that used her name—“Ginger and Fred”—under a defendant-friendly test: if the use is “artistically relevant,” and not “explicitly misleading,” it is protected by the First Amendment. In VIP Products, the Supreme Court neither overruled Rogers nor addressed the merits of the Rogers test. Instead, the Court clarified that the Rogers test does not apply where the allegedly infringing mark is used as a designation of source—i.e., as a trademark—for the alleged infringer’s own goods. The Court thus found that the Rogers test was inapplicable to the claim against VIP Products’s dog toy because it used the Jack Daniel’s trade dress as a trademark.

Second Circuit’s Decision

Against the backdrop of VIP Products, the Second Circuit articulated the “central issue” in the Wavy Baby case as “whether and when an alleged infringer who uses another’s trademarks for parodic purposes is entitled to heightened First Amendment protections, rather than the Lanham Act’s traditional likelihood of confusion inquiry.” The Second Circuit found that MSCHF’s Wavy Baby product was not entitled to the First Amendment protections of the Rogers test.

Specifically, the Second Circuit found that MSCHF used the Vans design as a source identifier, just as VIP Products had used the Jack Daniel’s trade dress. The Court reasoned that the Wavy Baby design evoked various elements of the Old Skool design, and that even the design of the MSCHF Wavy Baby logo mimicked the Vans Old Skool logo. The Court further reasoned that MSCHF admitted to “start[ing]” with Vans’ marks because “[n]o other shoe embodies the dichotomies—niche and mass taste, functional and trendy, utilitarian and frivolous—as perfectly as the Old Skool.” This, the Court concluded, was an indication that MSCHF had “sought to benefit from the ‘good will’ that Vans—as the source of the Old Skool and its distinctive marks—had generated over a decades long period.”

The Court then moved on to assess the likelihood of confusion caused by MSCHF’s Wavy Baby sneakers. In doing so, the Court found that Vans’ trademark rights in its iconic sneaker design were strong; that MSCHF’s Wavy Baby was similar to the Vans Old Skool design; that actual consumer confusion supported Vans’ claims; and that there was the potential for trade channel overlap at least in the secondary market for sneakers. The Court so found despite concluding that the quality of the parties’ respective products, and sophistication of consumers, did not favor Vans.

Conclusion

Much like the Supreme Court’s decision in VIP Products, the Second Circuit’s decision is a win for brand owners and a warning to creators, artists and parodists that seek to appropriate brand names and protected designs for artistic and expressive purposes. It also remains to be seen what is left of the Rogers test, and whether the curtailment of that test will have a chilling effect on free speech and creativity. But at least one thing is clear: in the wake of these recent decisions, parody or humor alone is unlikely to insulate infringers from U.S. trademark laws.

The case is Vans Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio Inc., 22-1006 (2d. Cir.).

[View source.]