Justice Sandra Day O’Connor protected us from the extremes

IN MEMORIAM

on Dec 11, 2023

at 3:38 pm

This tribute is part of a series on the life and work of the late Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Marci A. Hamilton is Professor of Practice in Political Science and Fox Pavilion Leadership Senior Non-Resident Fellow in the Program for Research on Religion, University of Pennsylvania.

We could use a Justice Sandra Day O’Connor on the United States Supreme Court right now. Her judgment and common sense protected the country from the extremes that have polarized this striving democracy. That polarization is no more apparent than on the Supreme Court right now.

Justice O’Connor’s greatest virtue on the Court, in my view, lay in her steadfast allegiance to her own moral center, regardless of what the right demanded of her, and despite being appointed by President Ronald Reagan. On abortion, children’s rights, and women’s rights, she was a bulwark against the extreme right and the left, a strong center who decided each case according to her own lights. O’Connor wasn’t counting votes but rather listening to her conscience.

She was a champion for women from the start. At the beginning of her time at the Court, in 1982, she wrote the majority opinion in Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, which held that a state nursing school that barred males violated the equal protection clause. She reasoned that banning males from a state nursing school was based on tired stereotypes, which set the stage for the later decision in United States v. Virginia, which held that women could not be denied admission to the Virginia Military Institute.

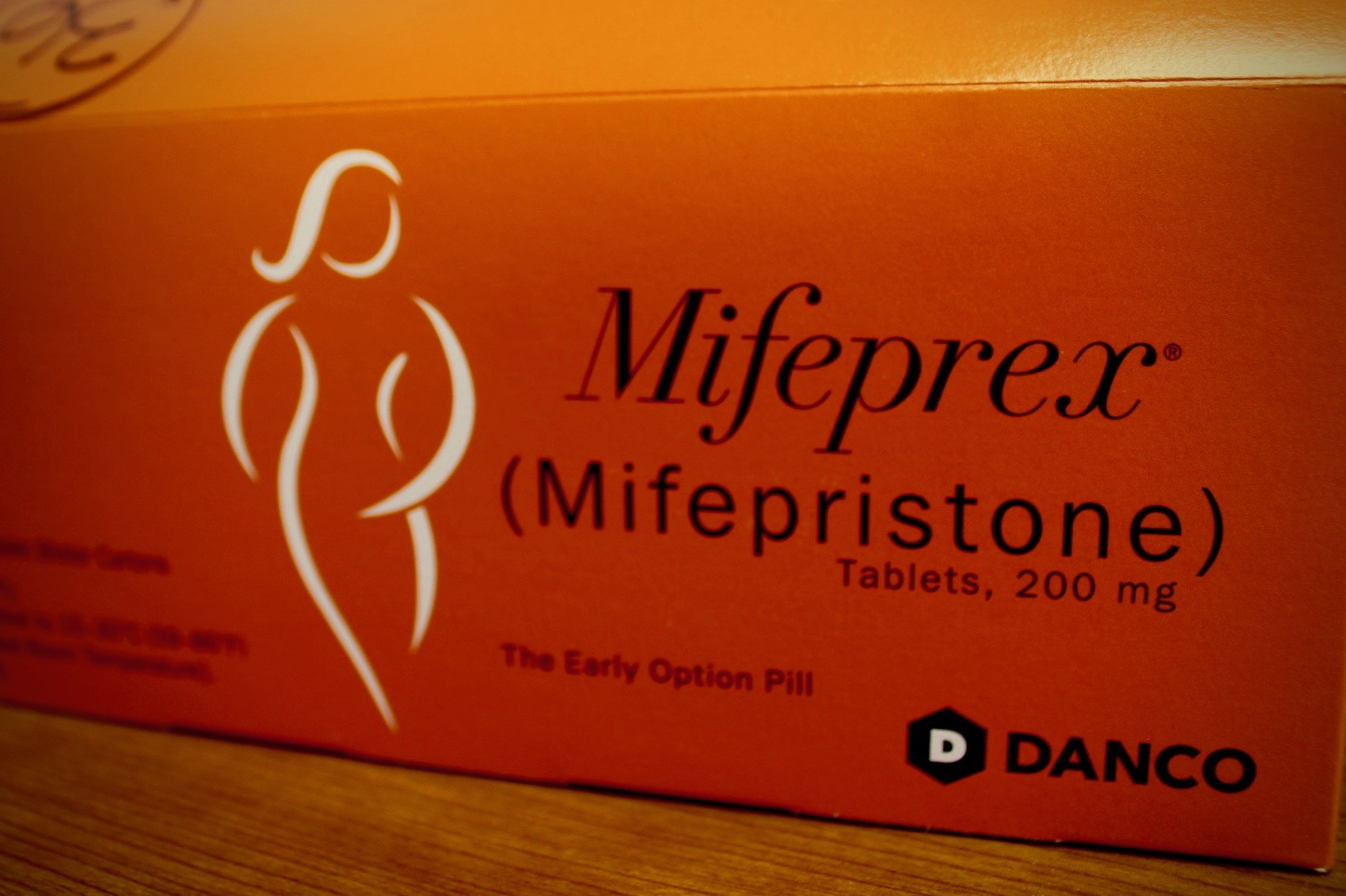

Just before I started clerking in the 1989 Term, the Court had issued the Webster v. Reproductive Health Services decision in which Justice O’Connor rejected the left’s arguments against most abortion regulations while at the same time refusing to overrule Roe v. Wade. O’Connor was willing to agree to the abortion restrictions in the law, annoying the left, but drew the line at interring Roe, which infuriated Justice Antonin Scalia, who denigrated her in his Webster concurrence, in which he tried to bully her into making that fateful move. She was unfazed, neither bowing to him nor picking up verbal arms against him then or later (I tried!). Several cases were teed up during our Term to overrule Roe, as the right apparently expected that she would bend, but she did not. When that became clear within the court’s walls, the challenges magically melted away before the Court could fully consider them—which, as a side note, shows the Federalist Society’s machinations at the Court as early as 1989 and her independence from it.

Justice O’Connor was also a leader for child protection and rights, as she refused to be cowed by the left and right’s devaluation of children’s well-being for the sake of adult rights and interests. In Maryland v. Craig, her majority opinion held that a child victim could testify via closed-circuit television rather than have to face the person accused of sexually abusing them in court. She held that the confrontation clause was not absolute, which left room to protect the child.

Similarly, in the abortion context, in Hodgson v. Minnesota, the Court considered a law that required a pregnant child to notify both parents to obtain an abortion. There was an exception if the child was abused or neglected, but the child was required to report the abuse to the authorities to be able to obtain the abortion, which meant both parents were notified—including the alleged abuser. In other words, a child in an abusive home had to put herself in danger to exercise her right to an abortion. Justice O’Connor wrote a separate opinion that provided the fifth vote to hold the two-parent notification unconstitutional. Ever the pragmatist, she explained her vote by pointing to the facts: only half of Michigan’s children lived with both biological parents and one-third lived with only one parent. The two-parent hurdle was simply unreasonable and the potential harm to the child too great.

O’Connor’s resistance to the “Christian country” movement from the right was heroic. Before the contemporary Court swept away the primary structures of the separation of church and state and fell for the ahistorical concept that the establishment clause exists solely to protect religion from government (not government from religion), Justice O’Connor kept the theocrats from breaching the wall. She introduced the “endorsement test,” which reinforced the establishment clause principle that the government may not support a particular religious viewpoint and, instead, must endeavor to be neutral toward religion. She rightly voted against a Christian creche scene (Mary, Joseph, and Jesus in a manger) in a courthouse and a school-backed prayer at a public school graduation ceremony, because, as she said in Lynch v. Donnelly, they “send[] a message to non-adherents that they are outsiders, not full members of the political community.” Twenty-two years later, she elaborated: “Allowing government to be a potential mouthpiece for competing religious ideas risks the sort of division that might easily spill into suppression of rival beliefs.”

The Christian right positively and viscerally hated the “endorsement test,” for obvious reasons. If your mission is to turn the country back to a mythical time when it was unified by singular, fundamentalist Christian beliefs and/or to unite the power of a Christian minority with the government, the endorsement test is an insuperable barrier. The criticism actually felt personal, because their frustration seemed to come from some entitlement to control her, because she was a woman and/or a conservative. Sadly, as soon as a majority of justices were appointed who shared the same Christian religio-political perspective, they dispatched with the test. Her memorable question in 2005 in McCreary County v. ACLU, where she tendered the decisive vote to hold unconstitutional a Kentucky courthouse’s Ten Commandments display, remains relevant: “Those who would renegotiate the boundaries between church and state must therefore answer a difficult question: Why would we trade a system that has served us so well for one that has served others so poorly?”

History will record that Justice O’Connor’s moral center was unyielding to the conservatives’ rightward lunge during her tenure on the Court. She was bemused and even amused by her new label as a “liberal,” but she defied easy categories. She was Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, period, and we are all better for her example and service.