Recent Evidence Raises Questions on Efforts to Silence Dissent at the Federal Circuit

“[T]he available evidence does not support the Complaint’s contention that Judge Newman’s performance has adversely changed in any statistically-significant way compared to that of her colleagues on the court.”

As the readers of this blog know, the Special Committee of the Judicial Council of the Federal Circuit is investigating a complaint identified against Federal Circuit Judge Pauline Newman. The Complaint alleges that Judge Newman “is unable to discharge all the duties of office by reason of mental or physical disability.” As a result, the Complaint essentially alleges, Judge Newman has authored too few majority (including unanimous per curiam) opinions compared to her colleagues, ignoring altogether the disproportionately larger number of her authored dissenting opinions.

In the latest update to the investigation, Judge Newman yesterday filed a Memorandum of Law in Support of Plaintiff’s Motion for a Preliminary Injunction asking the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to enjoin the Special Committee from continuing the suspension of Newman’s judicial functions. Newman argues in part that her medical records do not corroborate the Complaint’s accusations that she suffered a heart attack and has a coronary artery disease and that a recent examination by “a qualified neurologist…revealed no significant cognitive deficits and led that expert to conclude that Judge Newman’s ‘cognitive function is sufficient to continue her participation in her court’s proceedings.’”

Prejudicial Productivity Standard

In a breathtaking admission, the Judicial Council of the Federal Circuit, comprised of all active Federal Circuit judges, complained in its Order of June 5 that Judge Newman’s conduct necessitated “several interventions over the previous 18 months in which cases had been reassigned from her to another judge following … the circulation of draft opinions that no other member of the panels would join.” Normally, these draft opinions would be called “dissents.”

This one-sided majoritarian focus discards the utility of dissenting opinions and prejudices their authors. Whether intended or not, the unavoidable inference from the Complaint’s prejudicial productivity standard is that Judge Newman’s alleged “disability” impedes her ability to author sufficient number of majority and unanimous opinions that “other member of the panels would join.”

When authorship of only majority or unanimous opinions becomes the standard of productivity to which a judge is held by her Chief Judge, there is great cause for concern that dissents on the court are discouraged, if not silenced. This is particularly so when that standard is used to reassign cases for which the judge drafts dissenting “opinions that no other member of the panels would join,” and to justify removal of the judge from a Presidentially-appointed, Senate-confirmed office.

Nevertheless, if true, the allegations of Judge Newman’s productivity loss and “habitual delays” are serious enough to warrant further study of the evidence. To this end, my recent article provides an analysis of the facts as independently obtained from a comprehensive Federal Circuit decision dataset. The analysis reveals that Judge Newman was by no means an under-performer among her colleagues on the court.

Statistical Analysis of Federal Circuit Decisions

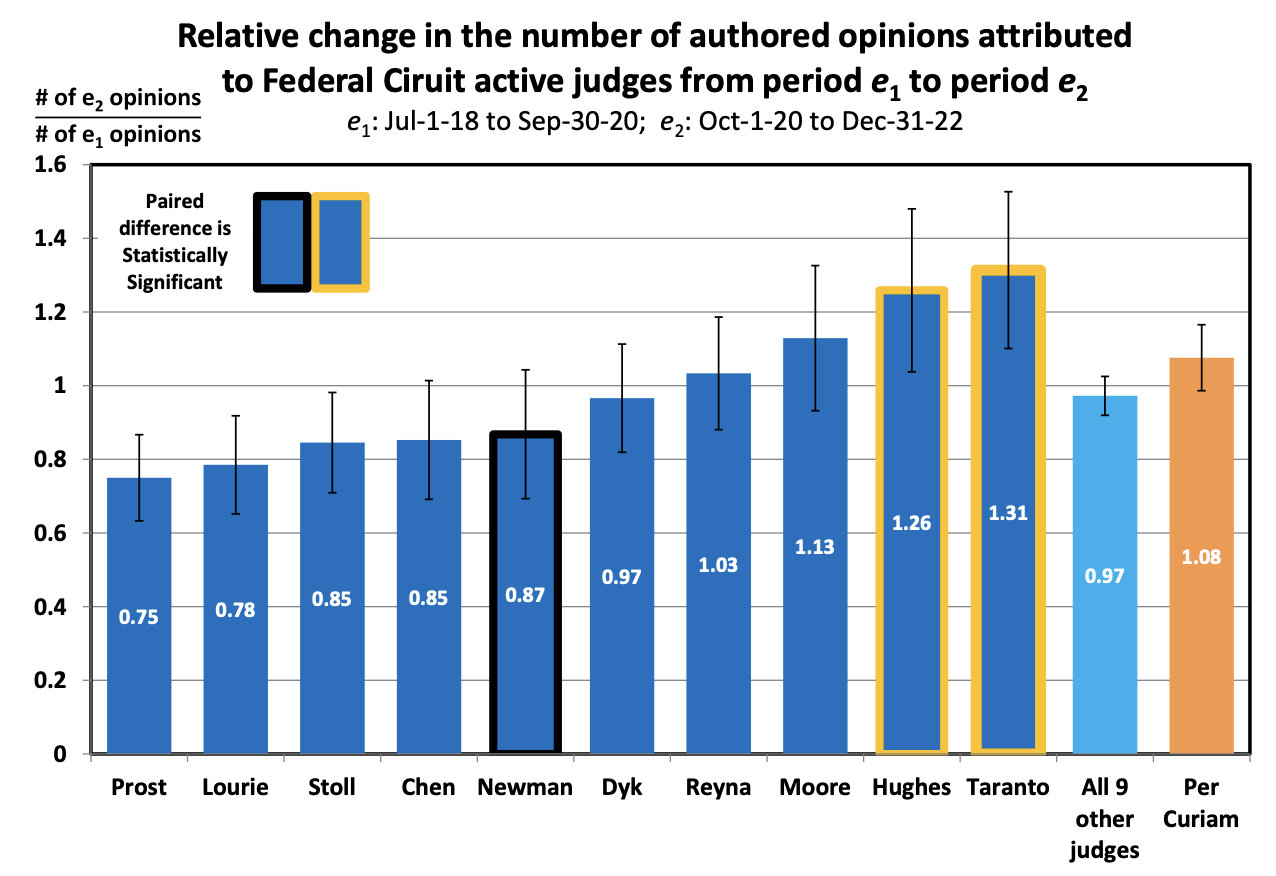

I conducted a temporal trend analysis comparing the number of authored panel opinions over two consecutive periods, the latter being the period during which Judge Newman allegedly suffered a “disability.” One such analysis shows that the relative change in the number of authored opinions attributed to Judge Newman between those two consecutive periods was statistically indistinguishable from the corresponding relative change in the number of authored opinions attributed to all other active judges over these consecutive periods (see figure below). The inference is that any change in authored opinion productivity attributed to Judge Newman during the period of her alleged “disability” essentially tracked similar changes in the productivity attributed to her colleagues and must therefore be presumed unrelated to, or not caused by, specific attributes unique to Judge Newman’s performance.

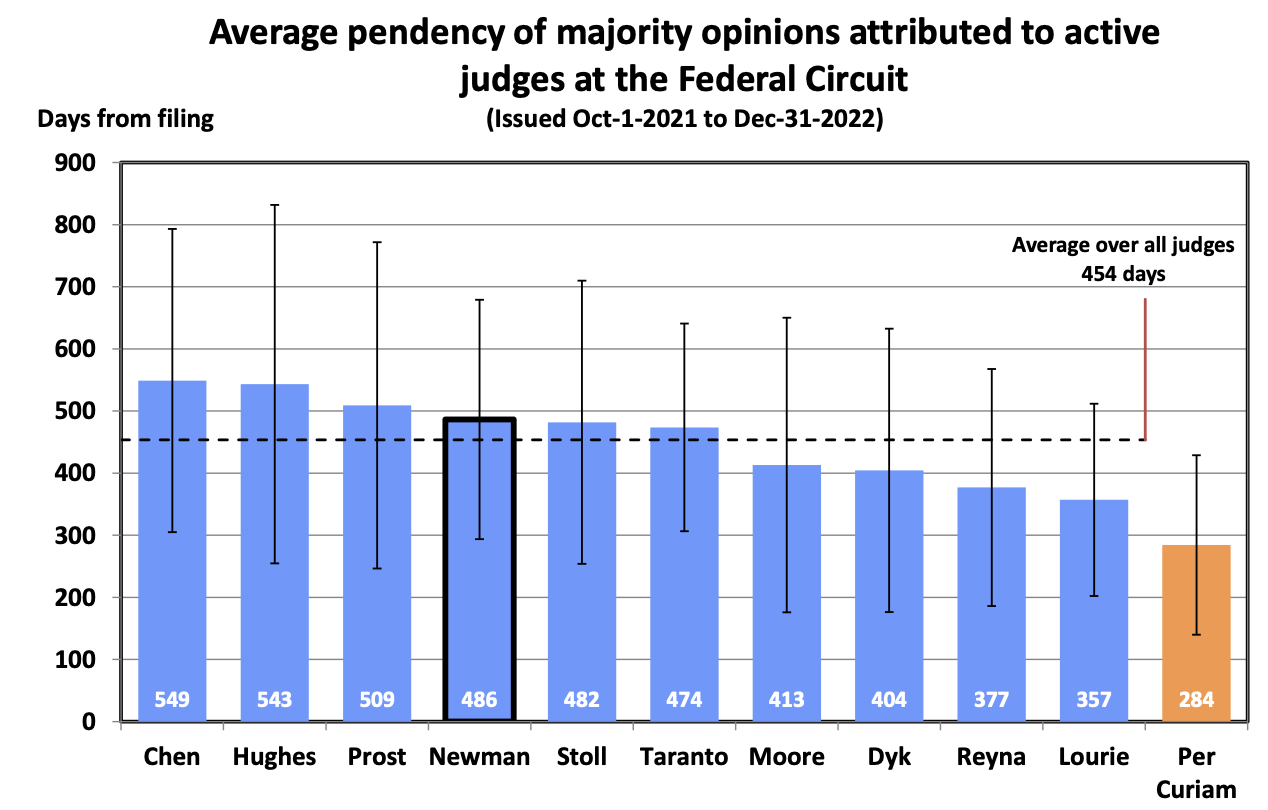

The Special Committee Order of May 16 argues that unlike the Court’s internal data, “public data reflecting the time between an appeal being docketed and terminated does not indicate the time between when a judge is assigned an opinion and when the opinion issues,” and that the “Court’s internal data also accounts for delays in authorship attributed to stays or reassignments.” It is true that the average pendencies shown in the figure above are based on the appeal filing date, pendencies that also include all preprocessing, briefing, screening, assignment, internal circulation for review, and docketing delays. However, for Judge Newman to appear an outlier with longer net authorship time consistent with this figure, the total pre-assignment delays for cases later assigned to her should have been disproportionately and materially shorter than those for her colleagues. There is no evidence that the procedures of the Federal Circuit could have resulted in specifically expediting the authorship assignment only to Judge Newman. Full disclosure of the Federal Circuit’s internal data on case assignment dates, and more importantly, the extent to which the inclusion of per curiam opinion pendencies selectively biased the results downwards for judges other than Newman would be necessary for drawing any further conclusions.

My article reports on more statistical tests regarding service on panels and concludes that the available evidence does not support the Complaint’s contention that Judge Newman’s performance has adversely changed in any statistically-significant way compared to that of her colleagues on the court. My analysis reveals a much more nuanced account of the factors that affect the number of authored opinions by any given judge. These factors in any given case are much less subject to the judge’s control than the Complaint implies. For example, the panel’s dynamics and propensity to adopt per curiam, or Rule 36 decisions impose a disproportionate systemic constraint on a dissenting judge’s opportunity to author opinions, which has little to do with productivity.

Potential Conflict of Interests

A dissenting judge necessarily creates additional workload for her colleagues. The additional workload for colleagues is palpable: not only is the dissenting judge taken out of the contributing pool of majority opinion authors for those cases, but her colleagues are assigned the additional majority opinion authorship jobs. Furthermore, those majority opinions that her colleagues must author in the face of her dissents take substantially more work, as they are lengthier and must not only address the merits of the case but also the specific grounds and precedents raised by the dissent. My analysis shows that assuming a 12-active-judge court, replacing Judge Newman (who dissents 53% of the time) with a new Circuit Judge, having a 5% dissent rate (the average for all other active judges in this study), would result in substantial authorship workload reduction by an average of about 5% for each of her colleagues. Her colleagues who would derive personal benefit from that workload reduction are members of the Special Committee investigating Judge Newman’s alleged productivity loss, and more broadly, all other members of the Judicial Council of the Federal Circuit, the body currently adjudicating the Complaint that seeks to remove Judge Newman from active office. This is a structural bias.

The appearance of a conflict of interests raises substantial questions as to the structural bias, including in the setting of the prejudicial standards and collecting evidence for evaluating Judge Newman’s productivity in comparison to her colleagues on the court. It raises serious questions as to the refusal of her colleagues to transfer the matter to an independent Judicial Council for investigation and adjudication. Ultimately, there is a question whether the Complaint seeks to remove Judge Newman from office to silence dissent at the Federal Circuit.

This question deserves heightened scrutiny in the case of the Federal Circuit—the sole appellate tribunal nationwide for appeals under the patent law since 1982. Decisions under other laws from multiple circuit courts of appeal provide a safety net through the national diversity of circuit holdings on a given subject. In contrast, suppressing dissent at the Federal Circuit is far more dangerous as it removes the safety net by putting a nationwide stranglehold on any opposing view and creating a singular decision on a subject, which the Supreme Court is less likely to review.

Download my full article at SSRN