What ‘Lawful Pathways’?

The Biden administration is telling migrants there will be consequences if they cross the border without taking advantage of the “lawful pathways” they’ve created to allow inadmissible aliens into the United States — but we don’t see anything lawful about the new options.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced Thursday, April 27, 2023, an update to its strategy for the end of its use of Title 42, the public-heath order that has been used (to varying degrees) to expel certain migrants who have crossed the border illegally since March 2020. DHS says it is issuing these reforms to build upon the border strategy DHS announced on January 5, 2023. The plan, however, does little to actually deter illegal immigration into the United States. Instead, it allows the crisis to continue in a new, more opaque form.

What’s in the Biden Administration’s Border Plan?

First, DHS announced that it will be imposing “stiffer consequences” for failing to use a “lawful pathway” into the United States. Specifically, DHS states that it plans to “transition back to Title 8 [immigration] processing for all individuals encountered at the border [that] will be effective immediately when the Title 42 [public health] order lifts”. Under this strategy, which mirrors DHS’s January 5 plan, inadmissible aliens who illegally cross the U.S. Southwest border:

- Will generally be processed under Title 8 expedited removal authorities in a matter of days;

- Will be barred from reentry to the United States for at least five years if ordered removed; and

- Would be presumed ineligible for asylum under the proposed Circumvention of Lawful Pathways regulation, absent an applicable exception.

Second, DHS announced a significant expansion of “lawful pathways” into the United States. This includes:

- Expanded access to the CBP One mobile app. When the Title 42 order lifts, migrants of any nationality located in Central and Northern Mexico will have access to the CBP One app to schedule an appointment to present themselves at a port of entry rather than trying to enter between ports. With this app, DHS is allowing prospective migrants to schedule their unlawful arrival with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) for processing and likely release into the United States;

- A brand-new family reunification parole program, to allow inadmissible aliens from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Colombia to enter the United States via parole and receive work authorization in the United States; and

- Plans to double the number of refugees from Western Hemisphere countries. Of all the “lawful pathways” presented by DHS in either the January or this announcement, this is the only pathway with a legitimate grounding in law. The problem here, however, is that migrants will have to establish that they are, in fact, refugees. INA § 101(a)(42) defines refugees as individuals who are unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin because of “persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion”. The vast majority of migrants who have entered the United States illegally have been determined to not be eligible for refugee status for failure to demonstrate persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on one of those protected grounds (and are accordingly ineligible for asylum).

These “pathways” are being created in addition to the four parole programs that were newly created by DHS in January for nationals of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. DHS stated that it will continue to “accept” up to 30,000 aliens a month (or 360,000 a year) under these programs. DHS did not use the word “admit” to refer to the entry for these aliens because they are assumed to be inadmissible under law.

The Biden administration also recently expanded the Central American Minors (CAM) program, which was originally created under the Obama administration. CAM allows certain family members and minors from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to seek refugee status or parole to the United States.

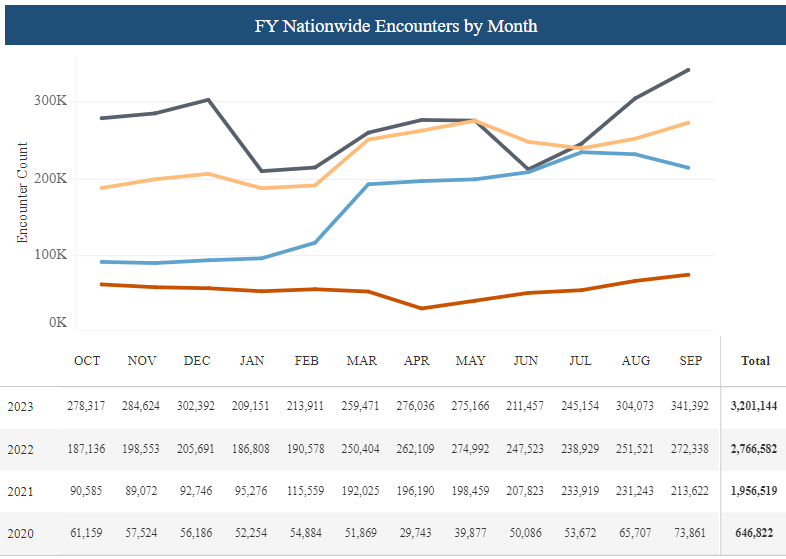

In total, the Biden administration is operating six parole programs to bring inadmissible migrants to the United States from countries with relatively high rates of border crossers. This strategy raises additional concerns given that, in recent years, nationals from around the world have been encountered in the border region. CBP officials confirmed encountering migrants from more than 160 countries at the southern border since 2021. In some months, non-Mexican and non-Central American nationals accounted for 43 percent of border region encounters — compared to just 4 percent five years ago. In November 2022, specifically, 63 percent of encounters at the border were from countries other than Mexico and the Northern Triangle region.

Accordingly, the CBP One app is operating as a “catch-all” device to still allow inadmissible nationals from all other countries to enter at a port of entry to claim an exception from enforcement. Once a port-of-entry appointment is obtained, an inadmissible alien is able to submit an asylum claim and be released into the United States with the potential to receive work authorization.

The primary difference between an entry of an inadmissible alien via a parole program and an unlawful border crossing is that in the case of parole, it is the United States government that is committing the illegal act — not the inadmissible alien who is entering with apparent permission.

To be clear, with exception to the refugee program, Congress has not authorized any of these “lawful” pathways. To call them “lawful” is farcical. The primary difference between an entry of an inadmissible alien via a parole program and an unlawful border crossing is that in the case of parole, it is the United States government that is committing the illegal act — not the inadmissible alien who is entering with apparent permission.

Congress has only conferred on DHS narrow authority to parole aliens into the United States on a “case-by-case” basis for “urgent humanitarian or significant public benefit” reasons. Parole was explicitly not created to circumvent the caps or mechanisms set by Congress, or otherwise to be used as a supplement to immigration policy. The administration simply stating that parole will be granted on a “case-by-case” basis does not cure the program’s legal deficiencies when each program lays out eligibility criteria for immigration benefits.

Even the New York Times has referred to this strategy as “back door” immigration to “allow hundreds of thousands of new immigrants into the country” via executive action alone. The New York Times correctly noted the parole programs to allow up to 360,000 migrants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela a year to enter and work in the United States will account for more people than were issued immigrant visas from these countries (pursuant to the immigration laws) in the last 15 years combined.

Even more concerning, DHS did not announce any numerical cap or limit to the number of inadmissible aliens it may allow to enter and work in the United States in any given year under its new family reunification parole program. This parole program has the potential to provide work authorization to more aliens per year than any nonimmigrant work visa program created by Congress.

What the Plan Doesn’t Say

Crucially, DHS’s plan says nothing about whether the agency plans to detain migrants who enter the United States illegally, consistent with section 235 of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Expedited removal procedures are not effective unless the government detains aliens until their proceedings have been completed because the availability of release into the United States is one of the strongest pull factors for illegal border crossings. While the announcement does say that DHS will make expedited removal decisions (which generally include credible fear screenings) in a “matter of days”, which implies some sort of detention or custody of aliens in proceedings, DHS Secretary Mayorkas testified last week that the agency will not be expanding detention to family units.

DHS’s unwillingness to detain migrants who enter the United States illegally has, in recent years, formed one of the largest pull factors that have jointly encouraged migrants to smuggle children with them into the United States. DHS has not been expelling family units under Title 42 or detaining those processed until Title 8 (the immigration authority). As my colleague Jessica Vaughan testified before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration Integrity, Security, and Enforcement this week: “Migrants are enticed by U.S. policies to put themselves, and their children, in risky situations to cross the border illegally, led by criminal smuggling and trafficking organizations, and enabled by government agencies and contractors that have looked the other way at the abuse and exploitation that frequently occurs en route to the United States and after resettlement.” This is exacerbated by DHS and the Department of Justice’s new regulatory proposal, which includes a carve-out to exempt family units who enter the United States illegally without pursuing a “lawful pathway” (i.e., entry via CBP One or after receiving parole) from asylum ineligibility.

DHS officials have also not said what they plan to do once these aliens’ parole expires. Parole is not a lawful immigration status, but rather temporary permission to enter and remain in the United States. A parolee is still considered an applicant for admission, and their parole may be terminated by DHS at any time.

It is unlikely, at least under this administration, that DHS will engage in any sort of spirited enforcement campaign to remove aliens whose temporary parole periods have expired. It is more likely that DHS will allow aliens to have their parole extended, much like its treatment of the Temporary Protected Status program, which has proven to be anything but temporary.

Reforms Are Needed

Ironically, the DHS’s press release states that “These measures do not supplant the need for congressional action. Only Congress can provide the reforms and resources necessary to fully manage the regional migration challenge.” While we at the Center strongly agree with DHS’s assessment of the need for legislative reform, Congress’s repeated rejection of legislation is itself an action, not an oversight. It demonstrates the complexity of the issue, which directly affects many wide-reaching social and economic interests, and the need for political deliberation and negotiation to balance these interests. It is not an invitation for unilateral executive action.

If the Biden administration genuinely wishes to stop the mass illegal-immigration crisis, it has tools within the existing legal framework:

- DHS can rescind its policy memoranda that prohibit immigration enforcement officials from initiating enforcement actions, including worksite enforcement, in large portions of the United States against large portions of the population in the United States illegally. These policies have sent the message to the world that this administration is not interested in enforcing immigration law against the vast majority of aliens in the United States illegally.

- DHS can also restart and strengthen implementation of section 235(b)(2)(C) of the INA (which was called “Remain in Mexico” or the Migrant Protection Protocols during the Trump administration) to prohibit the release of border-crossers into the United States until after their (prioritized) immigration proceedings are completed. The Biden administration can also work with the government of Mexico to ensure migrants returned to Mexico are adequately accommodated while they wait.

- DHS must also close loopholes in the asylum system that encourage aliens with fraudulent claims to submit credible fear claims for the sole purpose of release into the United States. This includes ending the 1997 Flores Settlement Agreement, a court order that restricts DHS’s ability to detain family units in family residential centers beyond 20 days (the time period in which the court — at that time — thought expedited removal proceedings could be completed) and strengthening the credible fear process to ensure it functions as an actual screening for asylum eligibility, not an expensive formality, among numerous other necessary reforms.