Too Many Patent Suits? The Data Suggests There are Too Few

“Given the incredible number of active patents, the question is not ‘why are there so many suits?” but “why are there so few?’”

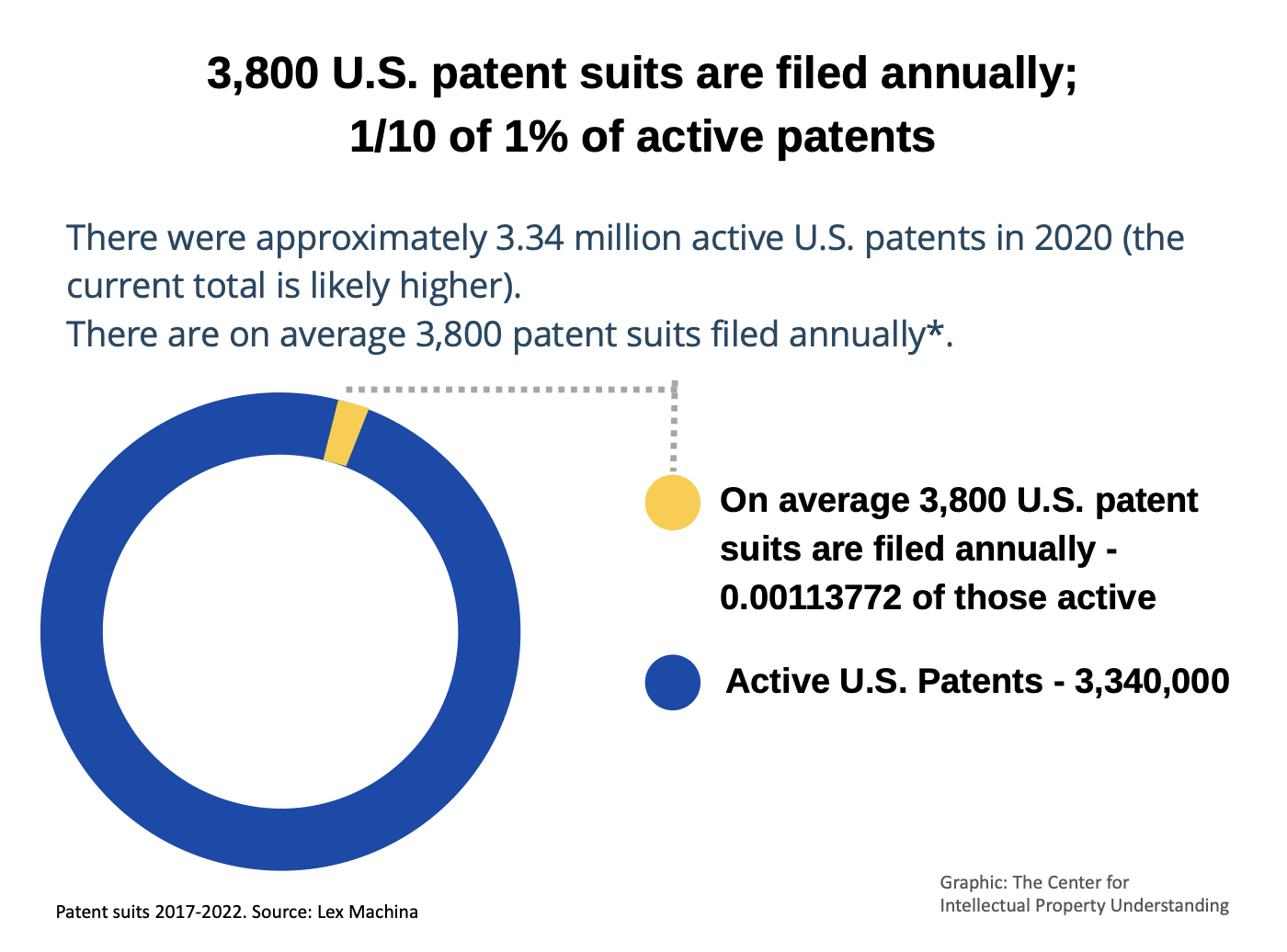

The simplest facts are sometimes the most difficult to comprehend. Patent suits are not as pervasive as they are portrayed in the media or by defendants. Remarkably few are filed relative to the number of patents that are active.

The necessity to litigate patent disputes to get the attention of potential infringers and hold a meaningful licensing discussion has likely increased the total number of suits filed. If it has, it has not had much of an impact on the net total. This suggests that many patent holders who should be suing are not.

Factoring out some 40% of suits that are attributed to volume filers, the work of primarily three NPEs, the figures are even more dramatic. Patent litigation is not the out-of-control, innovation-eating epidemic perpetuated by bad actors we have been led to believe.

As technology provides more opportunities to innovate and invent, it is no surprise that patent grants have grown. With the number of active U.S. patents increasing, the number of patent suits brought annually in U.S. district courts, including those brought by volume-filers, has been flat since 2017 and down since the introduction of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) in 2012. Despite the increased number of U.S. grants, patent suits are an increasingly smaller fraction of active patents.

Many potential tech licensees today will consider taking a license only if forced to in response to litigation. Plaintiffs must be prepared to wait as many as five years for a resolution and invest anywhere from a few million dollars to more than $10 million.

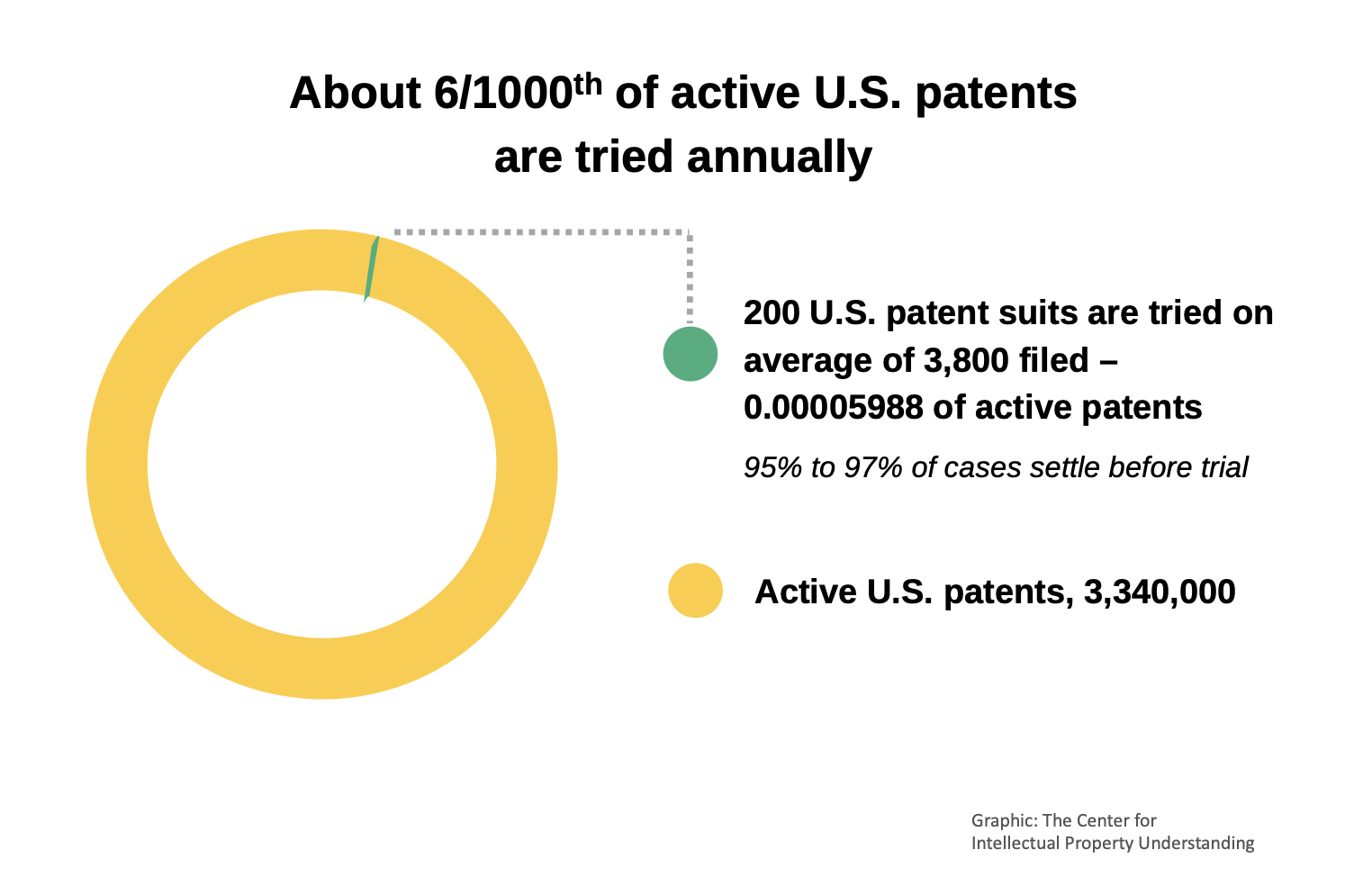

On average, 3,800 patent suits are filed each year. The number tried is only about 200, or about 5% of annual filings. As many as 97% of patent suits settle. Unfortunately, I am told, a potential licensor today must sue first to show it is serious. If that were not the case, there would likely be even fewer suits.

Given the incredible number of active patents, the question is not “why are there so many suits?” but “why are there so few?”

Four Million and Counting

There are approximately 3,340,000 active U.S. patents based on 2020 figures. In 2021, the USPTO granted a total of 327,798 utility patents; 325,445 were issued in 2022, bringing the estimated current total of active patents in the range of 4 million.

The average number of filed suits each year since 2017 is about 3,800. The number of those litigated to those in force is 0.00113772, or about one-tenth of 1%. Of the suits filed, annually, approximately 200 are tried, or 0.00005988% of active patents. That’s 6/1000 of active patents based on 2020 figures. Excluding so-called volume plaintiffs (see line graph below), of which three NPEs are responsible for most of the activity, patent suits are running at only about 2,300 per year since 2017, or about 1,500 (39%) less than the suit total. The trend is down from 10-year suit highs in 2013 and 2015 and flat since 2018, at a little over 2,200.

Patent Suits Excluding High-Volume Filers, 2013-2022

Beyond Shareholder Value

These figures illustrate the relatively small number of U.S. disputes compared to the increasing number of patented inventions. Of course, the litigation figure is high if you are a defendant facing a $100 million or more in potential damages, and perhaps dangerously small if you are a plaintiff who is subject to frequent and routine infringement, especially from those who can well afford to take a license.

If the top defendants were to pay damages on every alleged infringement (not that they should), it would be a veritable rounding error on their balance sheet, probably less than a few billion dollars. So why are they fighting so hard to avoid paying anything?

Patent defendants, including some of the largest and most esteemed technology companies, are focused on shareholder value. They equate a willingness to settle with weakness and overhead. They are loath to appear an easy licensing target, regardless of the ethics, and that litigation may cost them more in legal fees than a license would. It is a matter of shutting down potential adversaries before they can begin to acquire leverage. Incumbent leaders have turf to defend.

Defendants, even the largest, most successful ones, fear that significant damages or settlements will eventually erode their market dominance, even though they can readily absorb the cost to maintain it. More frequent licensing will open the door to higher plaintiff expectations and more lawsuits, and even greater licensing demands. No one likes a target painted on their back.

With AI and search technology positioned to better match patent claims with likely infringement, it seems inevitable that many companies will have to pay more for the inventions they use, unless even higher hurdles to licensing are introduced.

When the patents are weak or questionable, and the infringement vague, businesses certainly have the right to defend themselves. But the absence of injunctive relief for plaintiffs and indecisive courts, led by a lack of innovation policy, are a recipe for disfunction.

It is no surprise that those defendants most frequently targeted in patent suits – Apple, Samsung, Amazon, Google and Microsoft – are the largest, most solvent tech companies.

Just 13 non-financial companies in the S&P 500, including mainly giants like Apple (AAPL), Google-parent Alphabet (GOOGL) and IBD Long-Term Leader Microsoft (MSFT), are sitting on cash and investments of more than a $1 trillion, says an Investor Business Daily 2022 analysis of updated data from S&P Global Market Intelligence and MarketSmith.

Confusion Trumps Clarity

Apple’s cash on hand as of early 2022 was $202.5 billion, or 7.4% of the S&P 500. That number is down considerably, due perhaps to stock buybacks and market conditions, but the market value for the consumer electronics business remains at $2.5 trillion, an astounding number, higher than the GDP of many nations. The financial impact of settling infringement claims would be negligible. But that is not the point Apple and others are making.

Defending at all costs against patent disputes is about more than law. It is symbolic, and without injunctions that can halt product sales, it is smart, dare I say efficient, business from a shareholder perspective. For this reason, confusion is better than clarity.

If disputes are slow and expensive a lot of the alleged bad actors will go away. The problem is that many of the good ones will go away, too–those that deserve to be recognized for their contributions. There are likely a lot of them. It may not appear that way at first, but this spells trouble for innovation and commerce.

The next time you read there are too many patent lawsuits or NPEs, you may want to look at the facts. Apparently, not everyone cares to.