Doula Medicaid Training and Certification Requirements: Summary of Current State Approaches and Recommendations for Improvement

Introduction

Doula care is one of the most effective tools to improve health outcomes and reduce racial disparities among pregnant and postpartum people. A growing number of states are now recognizing the value of doula care, with ten states and Washington, D.C. providing Medicaid coverage for doula services as of February 2023. An additional five states are in the process of implementing coverage.

As states add Medicaid coverage for doula care, they face difficult questions regarding doula training and certification requirements. There are currently no mandatory licensure, certification, or credentialing requirements for doulas to practice in the United States. But to receive payment from a state’s Medicaid program, doulas must meet the state’s relevant qualification standards. Since doulas provide non-medical support, doulas as a profession have not historically sought licensing by state medical boards. Many doulas do, however, seek certification from private entities.

As of mid-2018, over 100 independent organizations offered some form of doula training and certification. These organizations include large-scale training organizations, such as DONA International and Childbirth and Postpartum Professional Association (CAPPA), as well as local and community-based training programs. But not all doulas seek certification. Some experienced doulas, who may have been serving clients in their communities for decades, are not formally certified. In a NHeLP survey of doulas practicing in California, 32 percent of respondents stated they had not received certification.

States seeking to provide Medicaid coverage for doula care must determine appropriate qualification standards for participating doulas. In doing so, states must balance protecting quality of care with ensuring fair access for doulas who want to serve, or who are already serving, Medicaid populations.

Summary of State Approaches

Training & Certification

States have taken a variety of approaches to doula certification requirements under Medicaid, with most states relying on independent training organizations.

(1) Complete a minimum of sixteen hours of training in listed areas and provide support at a minimum of three births; or

(2) Have at least five years of active doula experience within the previous seven years and attest to skills in prenatal, labor, and postpartum care through three written client testimonial letters or professional letters of recommendation.

- Florida allows each Medicaid managed care plan to determine its own credentialing procedures. Some plans have delegated credentialing to The Doula Network.

- Maryland requires doulas to be certified by one of nine approved doula certification programs.

- Michigan requires doulas to certified by one of nine approved doula training programs. Additional programs may be approved by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services with input from the Doula Advisory Council.

- Minnesota requires doulas to be certified by one of ten approved doula certification organizations.

- New Jersey requires doulas to either:

(1) Complete one of four approved New Jersey-based doula training programs; or

(2) Complete one of five approved doula training programs at a non-New Jersey site and complete a New Jersey supplemental community competency training.

- Nevada requires doulas to be certified by the Nevada Certification Board (NCB). The NCB requires doulas to complete one of eight approved doula training or doula certification programs.

- Oregon requires doulas to either:

(1) Complete one of eight approved doula training programs, all of which are currently Oregon-based. Individuals who hold national or non-Oregon state certification may be granted reciprocity or receive equivalent credit for previously completed training; or

(2) Provide evidence of attending ten births and providing 500 hours of community work as a birth doula, as well as a letter of recommendation from a previous employer for whom doula services were provided.

- Rhode Island requires doulas to be certified through the Rhode Island Certification Board. Certification requires completion of twenty hours of relevant education / training, defined as formal, structured instruction in the form of workshops, trainings, seminars, in-services, college/university credit courses, and online education.

- Virginia requires doulas to be certified through the Virginia Certification Board. Certification requires either:

(1) Completion of sixty hours of training from one of fourteen approved training providers; or

(2) Documentation of certification between 1/6/19 and 1/6/22 from one of eleven approved certification bodies.

- Washington, D.C. currently requires doulas to be certified by one of twenty-one approved doula training programs. The DC Department of Health is in the process of establishing its own certification standard; once complete, it will supersede the current reliance on outside professional certification bodies.

Additional Requirements

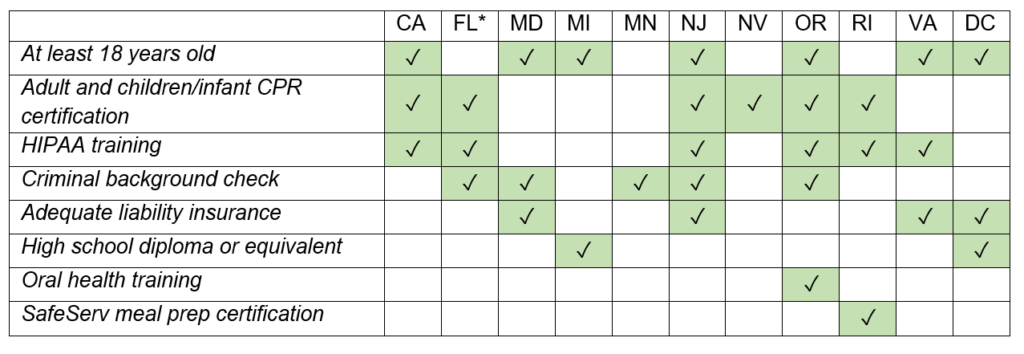

States impose various requirements for Medicaid doula providers in addition to training and certification standards. Many states require doulas to be at least 18 years old, CPR-certified for adults and infants, and trained on HIPAA compliance. Fewer states also require doulas to document adequate liability insurance, pass a criminal background check, or possess a high school diploma or equivalent. Oregon also requires Medicaid doulas to complete an oral health training, and Rhode Island requires training in food safety. The table below documents these additional requirements.

* Based on stated requirements of The Doula Network, which contracts with several Florida Medicaid health plans. Other Florida managed care plans may use other requirements.

Analysis

- Most states (eight out of the ten, including Washington, D.C.) that provide Medicaid coverage for doula services require doulas to be trained or certified by an approved organization.

Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, Nevada, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. maintain lists of approved doula training or certification programs. Doulas in these states generally must complete one of these approved programs to qualify for payment from Medicaid.

Each state’s list of approved programs is unique. Nevada, for example, has only approved eight programs, while Washington, D.C. has approved twenty-one. Moreover, some states merely list prominent national training organizations, while others list specific training sites located within the state. New Jersey, for example, has approved just four local training programs. The state also accepts training from an approved national training organization so long as the applicant also completes a New Jersey supplemental community competency training.

The most commonly accepted training programs are DONA International, CAPPA, Childbirth International (CBI), and the International Childbirth Education Association (ICEA). All four are large and well-known doula certification programs, where training can cost upwards of $700.

Doulas and doula advocates have expressed concern that such large training organizations are not best positioned to train doulas who will serve Medicaid populations. These well-known organizations mainly train doulas that go on to serve clients who can afford to pay directly out of pocket, with fees ranging from several hundred dollars to over $2,000. Moreover, these programs do not always include training in cultural humility or trauma-informed care, which can help doulas serve Medicaid enrollees with care and understanding.

Advocates have stressed the importance of cultural congruency and community-based training for effective doula care. Community-based doula programs, which offer culturally appropriate support tailored to the needs of the community, are uniquely qualified to serve communities of color and low-income communities. Organizations like Ancient Song and Tewa Women United offer community-based and -led training programs, yet these programs are less likely to be included in states’ lists of approved programs.

Finally, limiting certification to expensive training programs can pose barriers to a more diverse doula workforce. Large and well-known training programs can be prohibitively expensive for doulas from low-income communities, creating another barrier to entry for individuals who want to serve as doulas for Medicaid enrollees.

- Two states out of the ten do not require doulas to complete training or certification from a list of approved programs.

California and Rhode Island both provide slightly more flexible qualification standards.

California worked with a Doula Stakeholder Workgroup to craft two qualification pathways, one based on completion of formal training and one based on experience. For the Training Pathway, doulas are not restricted to a list of state-approved training programs. Instead, applicants are required to complete 16 hours of training in the following core areas: lactation support, childbirth education, anatomy of pregnancy and childbirth, nonmedical comfort measures, prenatal support, labor support techniques, and developing a community resource list. Doulas can demonstrate their training by either a certification of completion or an attestation, with an attached syllabus. These flexible certification requirements are the result of consistent advocacy by doula stakeholders, who foresaw how barriers to certification could impede doula access.

Rhode Island similarly does not limit training to state-approved programs. Instead, applicants must show they have completed 20 hours of relevant education or training, 12 hours of which must be in birth doula training, antepartum doula training, postpartum doula training, and/or childbirth education. Doulas must also train in lactation support and cultural competency. The Rhode Island Certification Board requires training to be “formal, structured instruction in the form of workshops, trainings, seminars, in-services, college/university credit courses, and online education.” Doulas must demonstrate their training with either training certificates or college transcripts.

- Only two states out of the ten provide a qualification pathway for doulas with significant experience.

California and Oregon provide a separate qualification pathway for doulas who have significant experience but who may lack formal training or certification. Such pathways are important tools to ensure experienced, community-based doulas are not excluded from Medicaid provider pools.

California offers an Experience Pathway under which applicants can attest to having at least five years of active doula experience in either a paid or volunteer capacity within the previous seven years. Applicants are also required to demonstrate their skills in prenatal, labor, and postpartum care through three written client testimonial letters or professional letters of recommendation.

Oregon similarly provides a Legacy Pathway for doulas without formal training, but the requirements are harder to meet. Applicants must submit “verifiable evidence” of attending 10 births and providing 500 hours of community work as a birth doula, as well as a letter of recommendation from a previous employer for whom doula services were provided.

- A growing number of states are recognizing the need for flexible training requirements.

Many states in the process of implementing Medicaid coverage for doula care have acknowledged that rigid training requirements can pose barriers to expanded access. In Illinois, the Sustainability Subcommittee of the Home Visiting Task Force recommended “prioritizing accessibility” in doula qualification requirements. The report stated, “In some states, overly stringent requirements for providers, for example requiring that doulas be certified by a national training organization like DONA, has limited the pool of providers able to successfully bill for Medicaid reimbursement.”

In Connecticut, the scope of practice committee was tasked with assessing whether the state should establish a certification program. The committee members concluded that certification training standards “should be based on core set of competencies rather than a select group of training programs, which may not represent the full spectrum of doula training models, including those delivered by community-based organizations that focus on doulas of color.”

And in Massachusetts, the Betsy Lehman Center for Patient Safety reported that surveyed doulas “worried that the training programs run by Black and brown doulas, those that train on skills critical for supporting birthing people who have historically had diminished experiences and outcomes, would be overshadowed by a process that primarily or only recognizes . . . Westernized, white-dominant training programs like CAPPA and DONA International.”

But this recognition is not universal among states in the process of implementing Medicaid coverage for doula care. Ohio, for example, plans to require doulas to be certified by one of eight approved national training programs.

Recommendations

Reviewing state approaches to doula training and certification provides some insight into how to design appropriate qualification standards.

- States should move away from requiring certification from specific organizations for doula qualification standards.

Such restrictions limit the number of potential doula providers and can pose expensive and administratively difficult barriers for marginalized doulas. Moreover, many doulas feel that large, nationally recognized training organizations—which are most likely to be on states’ lists of approved programs—are not geared towards serving marginalized communities. When states limit training to select organizations, they risk excluding local and community-based training programs that are closest to Medicaid populations and are best positioned to understand their needs. For more information on doula perspectives on certification, see Building A Successful Program for Medi-Cal Coverage For Doula Care: Findings From A Survey of Doulas in California. More flexible training and certification requirements better serve both doula providers and Medicaid enrollees.

- Instead of relying on a select group of training organizations, states should allow doulas to demonstrate training in core competencies, such as prenatal support, childbirth education, and lactation support.

The core competencies approach promotes high-quality care without unduly burdening doulas who wish to serve Medicaid populations. It also ensures that training standards reflect the wide variety of models, traditions, and practices that comprise doula care across communities. Furthermore, documentation of training should not be limited to training certificates, as some community-based training programs do not issue certificates.

- More states should create experience or legacy qualification pathways.

Many experienced doulas have been serving their communities for decades and have developed specialized skillsets and knowledge bases. They are trusted members of their communities, and many also serve as mentors and trainers themselves. However, these doulas may not be certified or formally trained because they learned through shadowing or apprenticeships. States should ensure these doulas are not excluded from participating in Medicaid by creating experience or legacy pathways, which can rely on attestations of experience and client testimonials. Such pathways should not require extensive documentation of doula experience, as doula care often operates outside of formal documentation structures.

- To ensure that qualification standards do not pose undue barriers to potential providers, states should also offer fee waivers, scholarships, and other types of financial assistance for doula training and certification.

Studies have shown that doula care is most effective when a doula is able to provide culturally congruent care. Thus, states should promote a diverse doula workforce that reflects the Medicaid population by ensuring equal access to training and certification for doulas from low-income communities.

- Most importantly, states should craft qualification standards in equal partnership with doulas—especially those who are already serving low-income communities and Medicaid enrollees.

Doulas are best positioned to understand the necessary core competencies for effective doula care, as well as what qualification standards are appropriate, accessible, and fair. States should ensure that community-based doulas and doulas who are Black, Indigenous, or people of color are fully represented and equal partners in these discussions.

Doula care holds incredible potential to improve health outcomes for Medicaid enrollees and reduce racial disparities. To deliver on these benefits, states must ensure their qualification standards do not create unnecessary barriers to entry for doulas who are dedicated to serving Medicaid enrollees.

*Kate Rohde was an intern at NHeLP in spring 2023.

For more information about the National Health Law Program’s work on Medicaid coverage for doula care, please see our Doula Medicaid Project page.