Justices search for a clear rule for confessions in joint trials

ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Mar 30, 2023

at 1:58 pm

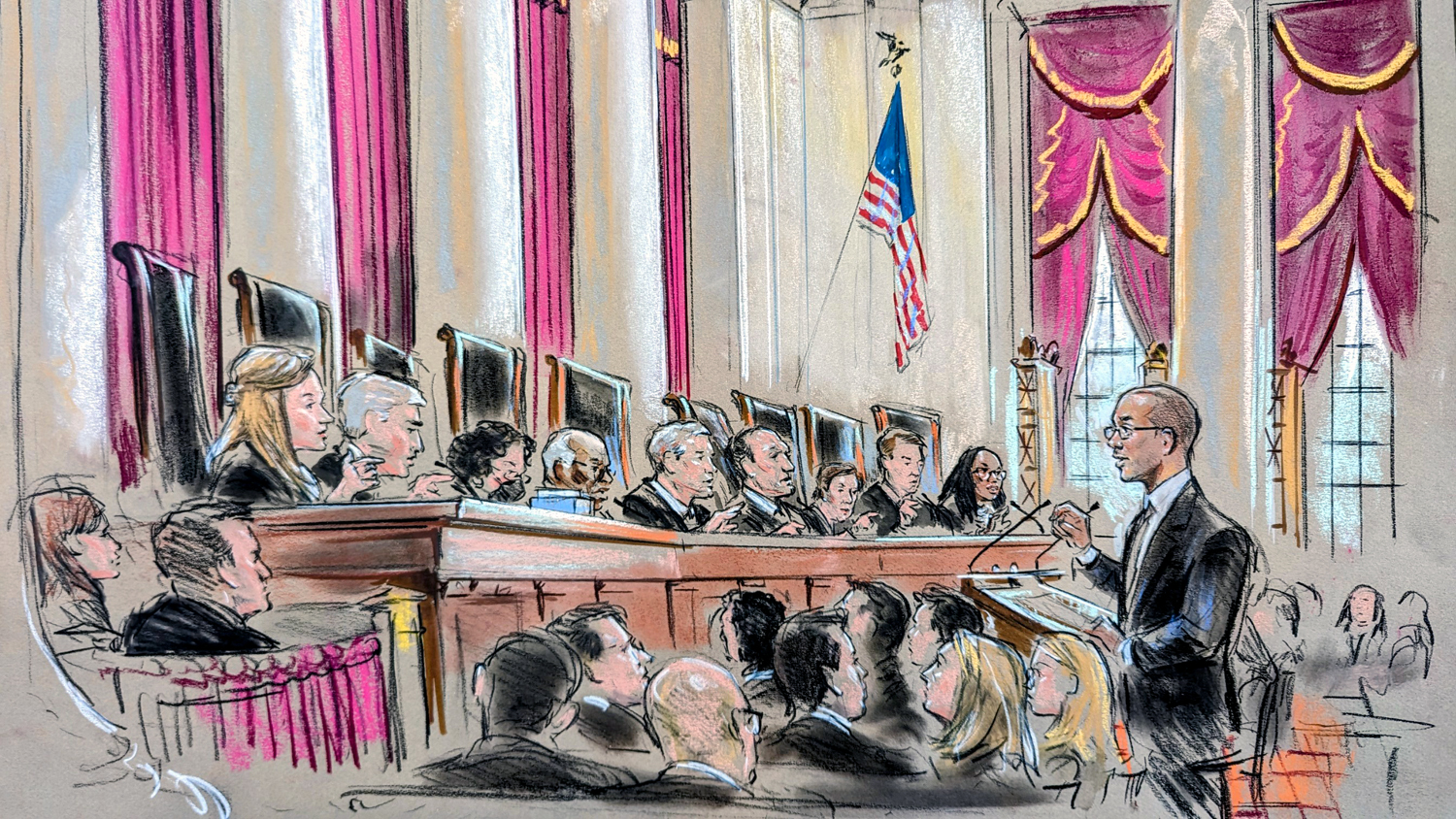

Kannon Shanmugam argues for Adam Samia in Samia v. United States. (William Hennessy)

In Wednesday’s oral argument in Samia v. United States, the justices explored the intricacies of the Sixth Amendment confrontation clause, evidence law, and jury instructions, as they sought to develop a workable rule governing the admission of confessions in trials with multiple defendants. It is not clear that they made much progress.

The dilemma arises in criminal trials when a non-testifying defendant’s confession implicates a co-defendant. Over 50 years ago, in Bruton v. United States, the Supreme Court held that confessions that explicitly incriminate a co-defendant violate the confrontation clause, which guarantees defendants in criminal cases the right “to be confronted with the witnesses against” them, even when jurors are instructed to consider those confessions only against the defendants who provide them.

In this case, the confession did not explicitly incriminate the co-defendant, Adam Samia, because it was redacted to refer only to an unspecified “other guy.” Samia’s attorney, Kannon Shanmugam, started off Wednesday’s oral argument by emphasizing that, in light of the other evidence admitted at trial, that redaction was ineffective. The jury would have quickly concluded that the “other person” was Samia, Shanmugam said, violating the spirit if not the letter of Bruton.

Finding the right precedent

The argument progressed in predictable fashion, with a few moments of drama. For the most part, the justices accepted the court’s precedents – Bruton and two subsequent cases – as setting the constitutional parameters; the argument centered on where this case fit within that caselaw.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson offered the strongest endorsement of Samia’s position, suggesting that the court would be “effectively overruling Bruton” if it endorsed such perfunctory redaction.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan also seemed sympathetic, indicating that the case was similar to the court’s 1998 decision in Gray v. Maryland, in which the prosecution introduced a confession that, in a token effort to comply with Bruton, substituted blank spaces for the co-defendant’s name. The court rejected this approach, explaining that “[r]edactions that simply replace a name with an obvious blank space or a word such as ‘deleted’ or a symbol or other similarly obvious indications of alteration … leave statements that, considered as a class, so closely resemble Bruton’s unredacted statements that, in our view, the law must require the same result.”

Justices Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh, and Neil Gorsuch resisted the comparison to Gray. Instead, they pointed to Richardson v. Marsh, in which prosecutors redacted all references (explicit and implicit) to the co-defendant and the court approved.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett and Chief Justice John Roberts offered hope to both sides. They proffered a “sliding scale” of admissibility, and they asked for a workable principle to distinguish sufficient from insufficient redaction.

Looking for a clear rule

Caroline Flynn, assistant to the solicitor general, argues for the United States. (William Hennessy)

Perhaps sensing that workability was the battleground on which the case would turn, the justices repeatedly returned to that question. Sotomayor was most explicit, warning Shanmugam that the “multifactor” test he proposed left her colleagues “worried” that “you’re going to have a mini trial before the trial” to determine the admissibility of confessions. Sotomayor offered a simpler test focused on the redacted confession and the number of defendants in the case.

Kagan similarly pushed Shanmugam on the point, asking him to explain how his multifactor test would work.

And Kavanaugh highlighted “an amicus brief from a lot of states … saying … that this could be a real problem.”

The United States, which was offering the simplest test, was happy to engage on the workability question. Assistant to the Solicitor General Caroline Flynn, representing the United States, contended that confessions only implicate Bruton if they are “facially incriminating,” which would include explicit references to a codefendant, obvious redactions, and even “things like nicknames, functional equivalents of the name” – but no more. This would avoid the prospect of mini-trials and, Flynn stressed, inconsistent rulings on appeal. To illustrate the point, Flynn deftly cited a judicial opinion on which Samia relied in which the appellate court “went through six double-column F.3d pages going through the evidence in order … to … conduct the Bruton analysis” and added “a footnote … where they acknowledged that they faced a case that had at least facially similar facts and came out a different way.” If Supreme Court advocates could get away with mic drops, that would have been the moment.

Still, as I mentioned in my case preview, the justices could decide that these workability concerns must ultimately bow to the confrontation right. In Melendez-Dias v. Massachusetts, for example, the court waved away similar complaints. The court emphasized that the confrontation clause “may make the prosecution of criminals more burdensome” but, from the founders’ perspective, that was a feature rather than a bug. There was little of that sentiment in the Samia argument, however.

Bruton is likely to survive

The most dramatic moments came when the justices and advocates seemed to dare each other to step beyond the narrow issue in the case. First, Alito asked Shanmugam: “Do you want us to examine the question whether Bruton was consistent with the original meaning of the Sixth Amendment?”

Shanmugam responded, “Nobody is asking you to do that.” But then, somewhat surprisingly, he suggested that Alito ask his adversary: “I think that’s a question for my friend, Ms. Flynn.” This was a calculated risk, because Shanmugam – a veteran of the Supreme Court bar – knew what the answer would be.

When Justice Clarence Thomas took up the invitation, Flynn disavowed any request to overrule Bruton. Later Sotomayor, perhaps seeking to lock in this concession, reiterated that point, saying to Flynn, “You’re not asking us to overrule Bruton, Gray, or Richardson, correct?” Flynn agreed.

The reason these moments were dramatic is that much has changed in the court’s approach to the confrontation clause since Bruton, and that case’s lack of historical grounding makes it vulnerable. But the court has already been through its share of controversy, and other battles loom on the horizon. Perhaps it should be no surprise, then, that there seems to be little appetite for making this fight any bigger than it has to be. That means that Bruton and its progeny will survive, leaving the justices to resolve only the narrow – but important – question of how much redaction is required.