Understanding Revenue Implications For State Pass-Through-Entity Taxes

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s $10,000 cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction managed to survive attempts to reform or scrap the policy during the last Congress, but that hasn’t stopped states from bypassing it. If anything, state activity in this area has accelerated, even though the provision is set to expire after 2025 (whether it will expire or be extended or reformed, is a totally different question).

Although the US Treasury Department disallowed some attempted workarounds to the SALT deduction limit, states have the greenlight to provide tax relief for filers with pass-through business income.

Here’s how it works: Under federal tax rules, the $10,000 cap applies to all individual filers, including business owners who report their earnings as pass-through income. However, C corporations, who pay taxes at the entity level, have no cap on their SALT deductions.

So, many states have enacted laws allowing pass-through businesses to pay taxes at the entity level in lieu of on their owners’ or shareholders’ individual income tax returns. All the business does is change how it files its taxes, and then business owners or shareholders can take the full SALT deduction against these earnings.

It’s not hard to see why the pass-through entity (PTE) tax has become so popular with states. It cuts taxes for their residents and businesses without reducing state tax revenue. It’s the feds who get charged for the workaround.

A pervasive trend

Support for the policy is bipartisan. Currently, about 30 states have enacted a PTE tax, up from 14 in June 2021. Connecticut became the first state to enact a PTE tax as a workaround for the SALT cap in April 2018. PTE taxes in Connecticut are mandatory, but elective in all other states.

State PTE tax structures and rules vary widely, which can lead to complications, especially for businesses operating across state lines. Whether paying a PTE-level tax reduces shareholders’ income tax liability or not depends on each state’s tax rates, credits, and deduction limits for individuals versus for PTEs.

If an election is made for a particular entity, the election is binding on all owners or shareholders for that tax year. But electing PTE taxes may not always be beneficial for all individual shareholders. For example, non-resident shareholders might not be eligible to receive a state tax credit, depending on the resident state’s laws.

How states account for this revenue is also complicated. For example, New Jersey and Virginia count revenues received from PTE taxes as part of personal income taxes, because that was where the revenue had previously been reported. Other states, such as California and Connecticut, count PTE revenues toward corporate income taxes, while Wisconsin counts it toward both personal income and corporate income taxes.

(For a current list of the states with elective PTE taxes and their effective dates see Table A7 of our latest State Tax and Economic Review quarterly report.)

Understanding PTE elective taxes and state coffers

PTE taxes can complicate understanding tax and revenue trends across different states. Declines in personal income taxes can reflect softening economic activity but also may be driven by this shift in where taxes are reported.

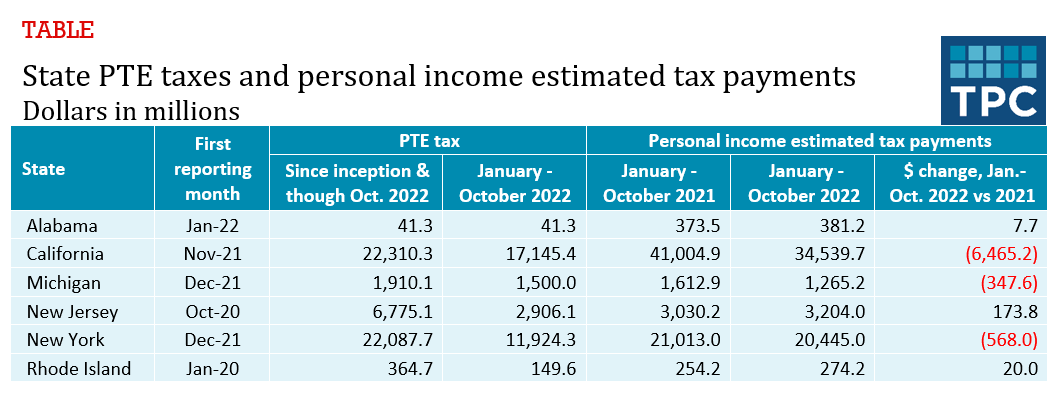

The Urban Institute’s State and Local Finance Initiative monthly tax data can shed light on these questions. The table below shows PTE tax collections since enactment in six states. (In other states, elective PTE taxes are still being implemented and data won’t be available until after the end of the tax filing season.)

California and New York have each collected over $22 billion from PTE taxes so far. Both states, as well as Michigan, have also seen declines in their personal income estimated tax payments during the first ten months of 2022. This likely reflects a shift in liability to the entity level, although declining stock values may have also driven down estimated tax payments.

PTE tax payments appear to have weakened in recent months. Most states require businesses to decide at the beginning of the year to opt in or not, so weakening across years could reflect entities determining the benefit was less than expected. Or weakening bottom lines for the businesses or partnerships could be at work.

Opting for PTE taxes was expected to lower personal income estimated payments. Some states had waived the requirement for PTE’s to make estimated payments. However, it is possible that some partnerships or S-corporations may have been making estimated payments voluntarily. So, the full impact of PTE taxes on personal income tax payments will be a lot clearer when tax filing season is over.

Last, but not least, it will take time for businesses and states to sort out the actual benefits of the new PTE taxes and how it affects different owners. Until then, we will witness more volatility in income tax revenue streams, which might also become moot at the end of 2025 if the SALT cap expires.