The Next Stage of Biden’s Migration Crisis

MEXICALI, Mexico – This northern Mexican city across from California is one of the latest to go live with an unreported, legally questionable new immigration strategy that President Joe Biden’s administration has discretely unfurled for months all along the U.S. southern border.

Twice a day, seven days a week since September, Mexicali city officials working closely with Biden’s U.S. Customs and Border Protection, on a secure shared “CBP-ONE” online platform, select hundreds of people a month for their escorted government-to-government handoffs through the land port of entry to Calexico, Calif. Once the Americans check their paperwork, they legally admit intending illegal border crossers like Nicaraguan Maria Esperanza Diaz Ruiz, 42, into the U.S. interior under a questionable authority known as “humanitarian or significant public benefit parole.”

Maria Esperanza Diaz Ruiz of Nicaragua waits at a Mexicali government shelter for imminent transport over the Calexico, Calif., port of entry.

They are free to start new lives under the benefit, with work authorization and the right to apply for asylum part of the package.

As she waited with 25 other selected immigrants for her legal ride to America, Maria told the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) she’d left home figuring she would have to pay smugglers to cross her over the border illegally. But up-trail word from friends reached her down-trail by cell phone that the Biden administration had legally admitted them and many others from Mexicali under the new humanitarian parole program.

They told Maria, “This is real. This is really a real program. This is not a magic trick,” she told CIS.

Maria came to Mexicali as soon as she could. A local migrant shelter took her in, and while she was fed and housed in relative security, American volunteers, lawyers, and activists helped her collect the documents America required: just the right documented story of woe, a psychologist attesting to suffered traumas and fear of returning home, proof of citizenship and identity, a clear criminal background, need for urgent free American medical treatment, and a sponsor in the U.S. willing to financially support the applicant. The story Maria proffered is that she worked for a government official in Nicaragua whose homosexuality drew death threats from her ex-husband, also a government worker, against her and her boss.

“I had to leave because I would be killed,” she claimed.

On that claimed basis, Maria was now waiting for a Mexican immigration service bus to drive her and 30 others in her group into America, still unable to believe her unlikely good fortune.

“I am so happy, so, so happy,” Maria said.

Teams of Mexicali city administrators work feverishly to enter each chosen immigrant into the CBP-ONE data portal so the Americans can pre-approve them for handoff at the Calexico border crossing.

After a couple of hours, a Mexican immigration van finally pulled up to the front. A white-uniformed federal officer swung open the van door as the 25 men, women, and children piled in with a few belongings. The bus transported them into a gated section of the port of entry, where they were to be handed over to Americans for processing. CIS was not allowed to follow beyond the gated area.

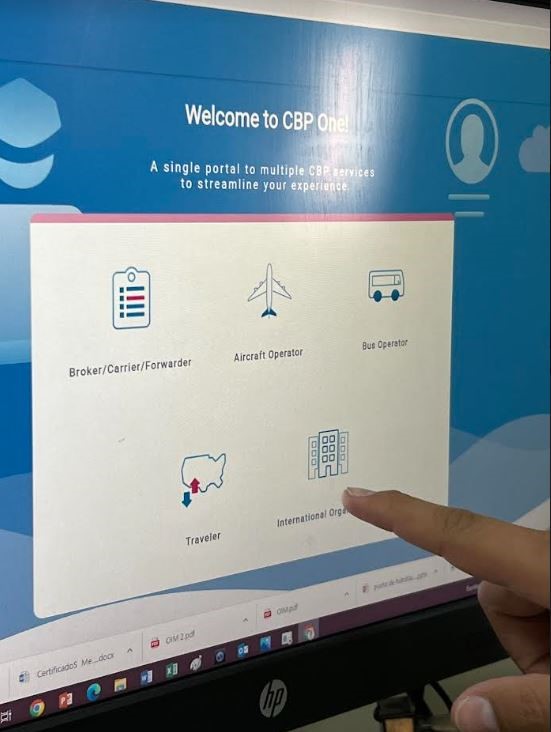

The CBP-ONE data portal provided to city of Mexicali officials for processing immigrants to the Americans.

The new face of Biden’s border crisis

Indeed, thousands are hearing about this new legal way in – and swamping an expanding system of Mexican shelters that gradually feed their occupants through American ports of entry with temporary legal status and opportunity to make the big move permanent. Local authorities are working to expand shelter facilities and establish new ones to accommodate the soaring demand for the legalized crossings, two shelter managers in Mexicali and one in Tijuana told CIS.

Mexicali city officials recently granted CIS rare, unfettered access to their side of the legalized border-crossing operation that began in September with President Biden’s Department of Homeland Security. Construction on a significant building expansion was underway on acreage behind it.

The Mexicali operation mirrors others just like it that began funneling increasing numbers of immigrants claiming tales of woe into the United States through ports of entry from the Pacific Coast to the Gulf of Mexico, the three shelter managers say. Mexico also appears to have set up operations well south of the American border, in Cancun on Mexico’s southern Caribbean coast and in Monterrey farther north, where pre-approved immigrants are flown into American airports.

This looks to be part of a purposeful strategy to create work-arounds to court-ordered expulsion policies but also to reduce politically painful illegal crossing statistics by channeling ever more people through these legalized crossings. While neither DHS nor the White House has publicized this legalized entrance program,DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has repeatedly telegraphed it in his oft-stated intentions to create “legal pathways” as part of the administration’s overarching “safe, orderly, and humane” vision for southern border immigration.

“Those who attempt to cross the southern border of the United States illegally will be returned. Those who follow the lawful process … will have the opportunity to travel safely to the United States and become eligible to work here,” Mayorkas said October 13 (Minute 22:01 to 22:17) in reference to the June 2022 signing of the Los Angeles Declaration for Migration and Protection at the Summit for the America’s Conference.

“This advances the Biden administration’s pledge under the Los Angeles Declaration for Migration and Protection to expand legal pathways as an alternative to irregular and dangerous migration.”

Maybe in keeping with the Los Angeles pledge, representatives of Biden’s DHS called Mexicali’s mayor in September 2022 with a “favor” to ask. At the time, hundreds of thousands of people were passing through the region to illegally cross through a gap left in the border wall in Yuma, Ariz., because of President Biden’s order to halt construction. That drew significant media attention two months before the U.S. mid-term elections with races in Arizona mattering for control of the Congress.

Aaron Gomez, a city of Mexicali official recently put in charge of running the Mexican side of the humanitarian parole handoff operation with the Americans.

“They needed to open a new entrance right here, and they needed someone to run it,” said Aaron Gomez, chosen to administer the new government shelter where final departure arrangements are made. “It was a favor the Americans asked for with this program.”

The Americans explained they saw the new Mexicali “entrance” as a way to improve immigrant safety.

“They’re going to cross either way. This will keep them from getting hurt,” Gomez recounted the Americans explaining.

Doling out humanitarian parole to illegal crossers is nothing new to Biden’s DHS; it has already bestowed it upon more than a million people who illegally crossed between ports of entry and presented themselves for the expected reward. The administration continues to hand it out to probably more than 150,000 a month crossing illegally, sending about 35 percent back to Mexico under court-ordered Title 42 or other authorities. (A federal court has ruled that Title 42 must be lifted on December 21, though Remain in Mexico will continue is some limited form.) These are far larger numbers than those escorted in over the ports.

So far, anyway.

But all indications suggest that this new form of legalized border crossing is morphing into a new next phase of Biden’s border crisis, where fewer are illegal but more enter.

Expanding out of public sight and mind

Some scattered media have tangentially reported the Biden administration’s recent application of the escort parole program to Venezuelans and Ukrainians. In August, the news outlet Border Report disclosed that foreign nationals who claimed to be gay found that they could also get the escort from Tijuana to San Diego on humanitarian parole.

But not seen anywhere in the popular media was that DHS was expanding the program all along the rest of the border and also deep inside Mexico, providing a work-around to court-ordered push backs but also an open avenue for people only interested taking advantage of it.

For instance, CBP is taking handoffs of regular Mexican citizens and giving them humanitarian parole. Providing such benefit to Mexicans is extremely unusual.

In fact, the majority of the 25 people CIS saw driven to a legal crossing on November 4 were Mexican citizens from the states of Jalisco, Michoacán, and Oaxaca. These men and women staked their applications to a recent spate of cartel violence in Baja and Sonora. But American asylum judges have always uniformly rejected Mexican citizen claims of cartel violence for asylum on grounds that they can find safe haven elsewhere inside Mexico, and Border Patrol routinely pushes back single Mexican men into Mexico under Title 42.

No matter; all of these Mexicans were approved for humanitarian parole because they lived in areas of cartel violence.

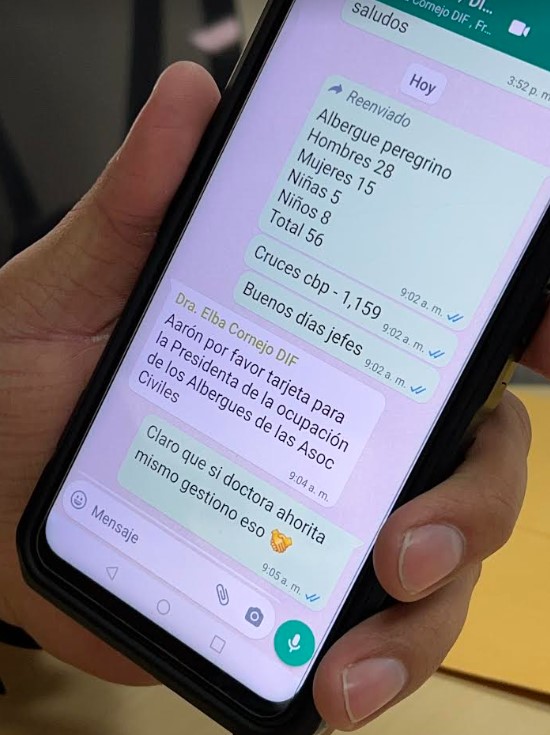

Shelter manager Gomez’s phone tallying immigrants he has arranged for hand-off to American immigration officials.

“Right now, I came here because I didn’t want to go home,” explained one young Mexican from Michoacán, where a wave of cartel violence in mid-2022 claimed 800 lives, making it Mexico’s most violent state.

But if cartel violence is rarely, if ever, accepted for humanitarian parole or asylum claims, so too is mere desire for family reunification with loved ones in the United States.

Yet family reunification seemed to be a driving desire among many of those CIS interviewed in Mexicali who were claiming humanitarian grounds. Also, evidence that immigrants had already illegally crossed the southern border and lived for years in the United States also did not disqualify them for this program.

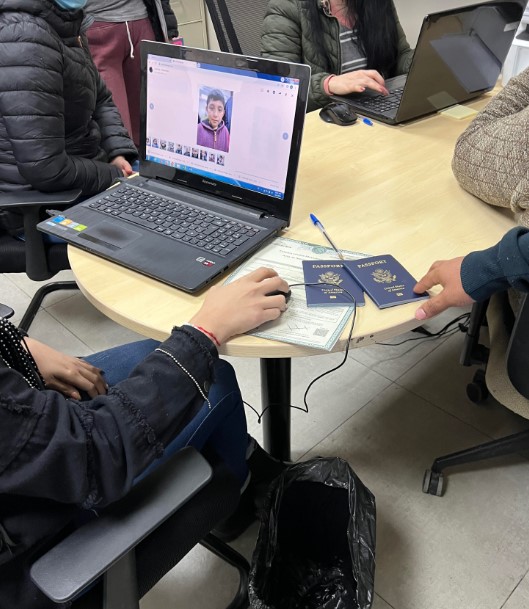

For example, one approved Mexican woman from Oaxaca, speaking as city workers entered her information in the CBP-ONE data portal, had illegally crossed the border and also lived illegally in North Carolina for years afterward.

A Mexican mother of two American children she gave birth to while living illegally in the US is returning with them seeking humanitarian parole for herself to join other U.S. citizen children still in the United States.

The woman, who did not want to be identified, had given birth to twin boys there, making them U.S. citizens and proving her prior illegal presence. But the mother said she returned with the American citizen twins to Mexico seven years ago, when they were toddlers, to rejoin her other non-U.S. citizen children still in Oaxaca. Now, the boys each had fresh U.S. passports and she was using the program to return herself with them so that they can join yet other U.S. citizen children she’d left behind in North Carolina.

That’s a family reunification motive, which is not supposed to be grounds for humanitarian parole. In fact, however, the DHS program now makes allowance for family reunifications over the border, a new opening for potentially vast numbers of claimants. The woman also was citing cartel violence from the summer for her claim. CBP went for it.

“Now I’m trying to go back and do everything right,” she said.

Also accepted for handoffs were young single men from El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, and others subjected to the court-ordered quick expulsion policies, which the Biden administration has been forced to retain against its will.

Is the administration using the escort program to evade court requirements?

“It’s helping everybody but especially the people effected by Title 42 and some MPP,” Gomez said, referring to the government abbreviation for the Remain in Mexico policy. “They chose these people to be the first ones because they were affected by Donald Trump. But many more are coming from South America. People keep coming.”

Elizabeth Gallardo, volunteer manager of the Posada del Migrante Shelter, one of seven in Mexicali feeding into the one Gomez manages, said all the shelters in town were jam-packed with about 3,000 people, as Guatemalans ride train tops and buses into town just to exploit the program. These are people who would ordinarily be subject to court-ordered expulsion programs.

“A lot of these are Central Americans and Mexicans because the Americans push them back,” Gallardo said. “Every day, people are getting here. Last night we had 45 men sleeping outside. They found a garage to sleep in because of the cold weather.”

Using a questionable legal authority with increasing gusto

One other reason why the Biden administration does not seem eager to publicize what it is doing at the ports: Some experts question the legality of its use of humanitarian parole.

“Humanitarian parole was never intended to be used this way, and Congress made it clear that parole is not meant to be a supplement to immigration policy,” said Elizabeth Jacobs, a CIS fellow and former U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services official, when informed that the escort hand-off program was being used much more broadly than reported. Jacobs said humanitarian parole can only be used on a case-by-case basis for no other purpose than urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.

“If these accounts are true, the United States government is acting directly in conflict with the limits and procedures established under federal law,” Jacobs said. “Escorting inadmissible aliens into the United States for the sole purpose of granting these aliens work authorization is a blatant abdication of DHS’s responsibility to uphold federal immigration law.”

Stealthily, perhaps with that in mind, DHS launched one early version of the handoff program in late 2021 in Reynosa, Mexico, where CIS discovered that Mexico was escorting hundreds of giddy immigrants every week for delivery to the Americans through a McAllen port of entry into Texas.

Nowadays, though, the program delivers immigrants, at the least, from Tijuana to San Diego, Agua Prieta to Douglas in Ariz., Juarez to El Paso, Nuevo Laredo to Laredo, Reynosa to McAllen, and Matamoros to Brownsville, the shelter managers say. It’s going on in interior Mexico too, they say.

How many have gotten through in this questionable manner is hard to find.

The U.S. government does not volunteer how many aliens without visas get this legalized turnstile treatment. But certain indicators point to many thousands more such crossings into the United States than when the program first piloted. CBP encounter data show a sharp trajectory of “encounters” at southern ports of entry (as opposed to crossings between the ports) over the past year, from 75,480 in 2021 to 172,508 in fiscal 2022. The Tijuana-San Diego port crossings shot from 37,492 in fiscal 2021 to 81,266 in fiscal 2022. The Nuevo Laredo-Laredo port crossing ballooned from 21,664 to 66,374.

In Mexicali, about two groups a day go over through back warrens of federal buildings, said Gomez, the administrator of the city’s main shelter where the CBP-ONE site is accessed and Mexican immigration buses pick up the migrants and deliver them to the Americans.

In a little more than a month of operation through November 3, the shelter had processed 1,159 immigrants to the Americans. But word spread down trail fast, and during the CIS visit, Gomez, the facility’s administrator, complained that it was now in so much demand that a major expansion was underway to triple its current size.

About ten of the approved-for-handoff immigrants said they had not previously crossed or tangled with the American system. They’d heard about the program on social media and headed north to get into the comfortable, well-provisioned line.

An American recipe for Mexican fraud and corruption

The system generally works pretty much like Mexicali’s everywhere else: After immigrants arrive in one of seven Mexicali shelters that feed into the final government one that Gomez runs, a battalion of non-profit migrant advocate volunteers help them collect required paperwork. The volunteers and the UN International Organization for Migration see to it that food, shelter, and clothing needs are provided while the immigrants hit the American requirements that they deserve humanitarian parole.

But fraud and corruption are strongly indicated. For example, the U.S. wants “proof” of psychological trauma for humanitarian parole, so the human rights non-profits provide psychologists to conduct assessments and provide written recommendations for the parole.

If applicants claim they’re fleeing danger, university law professors and students help them file police reports over the phone to home countries after the fact, then get the police reports sent back as “evidence,” three shelter managers confirmed. If immigrants want in on a claim of urgent medical need, the non-profits provide the doctors to attest to their desperate straits.

But two of the shelter managers said the system is easily and frequently gamed with the assistance of these volunteers who are not concerned about truthfulness. He said he believes many of the applicants say whatever they’re told will get them over the line.

Pastor Albert Rivera of the Albergue Agape shelter in Tijuana said he figures the U.S. lawyers and law students, human rights organizations and others helping foreign nationals gain humanitarian parole operate from ideological belief that all immigrants have an absolute right to enter the United States legally or illegally. The law students constantly coach the immigrants to demand political asylum and to never sign a document volunteering to return to Mexico.

Pastor Albert Rivera in Tijuana.

“That’s how they’re coaching. Everything right now is political,” Pastor Rivera said of the American lawyers and law students. “Their vision is for them [the immigrant parole applicants] to have a right to just jump over the border into the United States or just enter into the United States. It doesn’t matter if you jump the fence or whatever. And when you’re in the United States, you have a right to enter only with your word. Only with your word. Your word should be good enough.

“What I tell the immigrants is that these attorneys will get you into the United States but they cannot guarantee you that you’re going to win a case,” he continued. “They don’t care if you have a strong case and if you have evidence. They don’t care. What they care about is if you enter.”

So they’ll help the immigrants get over by any means necessary. In addition to gratifying their ideology, the lawyers and human rights groups are motivated to raise funds for themselves back in the United States.

“They get a whole bunch of fundraising,” Rivera told CIS. “Hollywood’s involved. A lot of people get involved in all that. You’d be surprised at everyone that’s involved.”

Worse than the lying and deceit on documents, Pastor Rivera said, is that the system now appears to be giving rise to corruption.

Immigrants tell him Tijuana city officials are demanding bribes of 5,000 to 10,000 pesos ($250 to $500) for them to get put on government shelter lists for faster and more guaranteed American crossings.

“That’s the problem that we have. They do it and right away they take you to one of the shelters and in 15 days they’re going to cross you over,” Rivera said. “They say, ‘look, I’ll put you in one of those shelters if you give me so much money. Give me money and then you can cross.”

One immigrant who became a volunteer in the new system started demanding a thousand pesos to “cross you right quick.”

“She got to deposit the money and everything. There’s a whole bunch of problems.”

Were the escort hand-off system continue to expand and become the norm, it would create economic and security incentives for even more to come. First, port escorts eliminate the need to pay thousands of dollars to Mexican cartel smugglers for the right to cross, providing a powerful financial incentive. Second, immigrants allowed in this way avoid criminal dangers in northern Mexico while they wait inside a shelter system that provides for all their daily needs.

The system benefits open-borders advocates and the Biden administration too, pleasing immigration doves in the Democratic Party who demand unimpeded cross-border travel and an end to immigration enforcement. But mainly, the numbers of legal hand-off crossings don’t add to the politically problematic apprehension statistics that worry some Democrats.

After all, technically, this could no longer be called “illegal immigration” if it’s been made “legal.”

And, even better for politicians and for hopeful migrants heading north, this kind of entry happens out of sight of news cameras, and therefore remains out of the public mind.