Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Business Tax Increases: Details & Analysis

Key Findings

- Starting in 2022 and continuing through 2026, businesses will face several tax changes scheduled as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), including a switch to five-year amortization of R&D expenses, the gradual phaseout of 100 percent bonus depreciation, a tighter interest deduction limitation, and an increase in international tax rates.

- Canceling the business tax changes would increase long-run economic growth by 0.6 percent and national income by 0.5 percent. The capital stock would increase by 1 percent, wages by 0.5 percent, and employment by 105,000 full-time equivalent jobs. After-tax incomes would increase across the income spectrum, by an average of 0.6 percent in the long run dynamically.

- The 10-year cost of canceling the TCJA business tax increases is about $751 billion on a conventional basis, but the cost falls to about $568 billion on a dynamic basis when factoring in additional tax revenue from economic growth. Over the long run, the annual cost would be much smaller after timing-related changes associated with 100 percent bonus depreciation and R&D amortization fade, costing less than $20 billion annually in 2022 dollars on a dynamic basis.

- Due to the resulting economic growth from making these provisions permanent, deficits and debt as a share of GDP would decline on a dynamic basis. Debt as a share of GDP in the long run (30 years) falls from 185 percent under baseline current law in 2052 to 184.2 percent with these provisions made permanent.

Review of Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Business Tax Changes

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act made several large changes to business taxes, including permanently lowering the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. Many of the other business tax changes were temporary or scheduled to change over the ensuing decade, in large part to reduce the deficit impact of the bill and to pay for a permanently lower corporate tax rate.

Starting in 2022 and continuing through 2026, businesses will face several scheduled tax changes that will raise their tax burden compared to the tax policy that prevailed from 2018 to 2021 (see timeline below).

In this paper, we model the following changes to the TCJA business provisions:

Canceling the amortization of R&D expenses

Prior to the TCJA, when a company spent money on research or experimentation, it was allowed to deduct the full cost of the expense immediately. Businesses’ ability to expense their research and development (R&D) investments has been part of the federal tax code since at least 1954.

But under the TCJA, beginning in tax years after December 31, 2021, companies that invest in research and experimentation will generally be required to deduct their investment costs over five years. The change raises the cost of making research investments in the United States and increases the tax burden on businesses that spend money on R&D.[1]

Canceling the switch on the business net interest deduction from EBITDA to EBIT

Prior to the enactment of the TCJA, businesses were generally allowed to deduct their total amount of interest paid, subject to a few minor limitations. The TCJA created a new limit on the deduction for business interest paid, intended to reduce the tax code’s preference for debt over equity.

Starting in 2018, companies are generally no longer allowed to deduct net interest above 30 percent of their “adjusted taxable income,” defined as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). But after 2021, the limitation became significantly tighter by switching from EBITDA to earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).

Making 100 percent bonus depreciation permanent

One of the most significant provisions in the TCJA, 100 percent bonus depreciation allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of most short-life business investments, such as equipment and machinery, substantially lowering the cost of investing in the United States. The provision is scheduled to begin phasing out after the end of 2022 until it fully expires after the end of 2026, requiring businesses to delay write-offs for investment.[2]

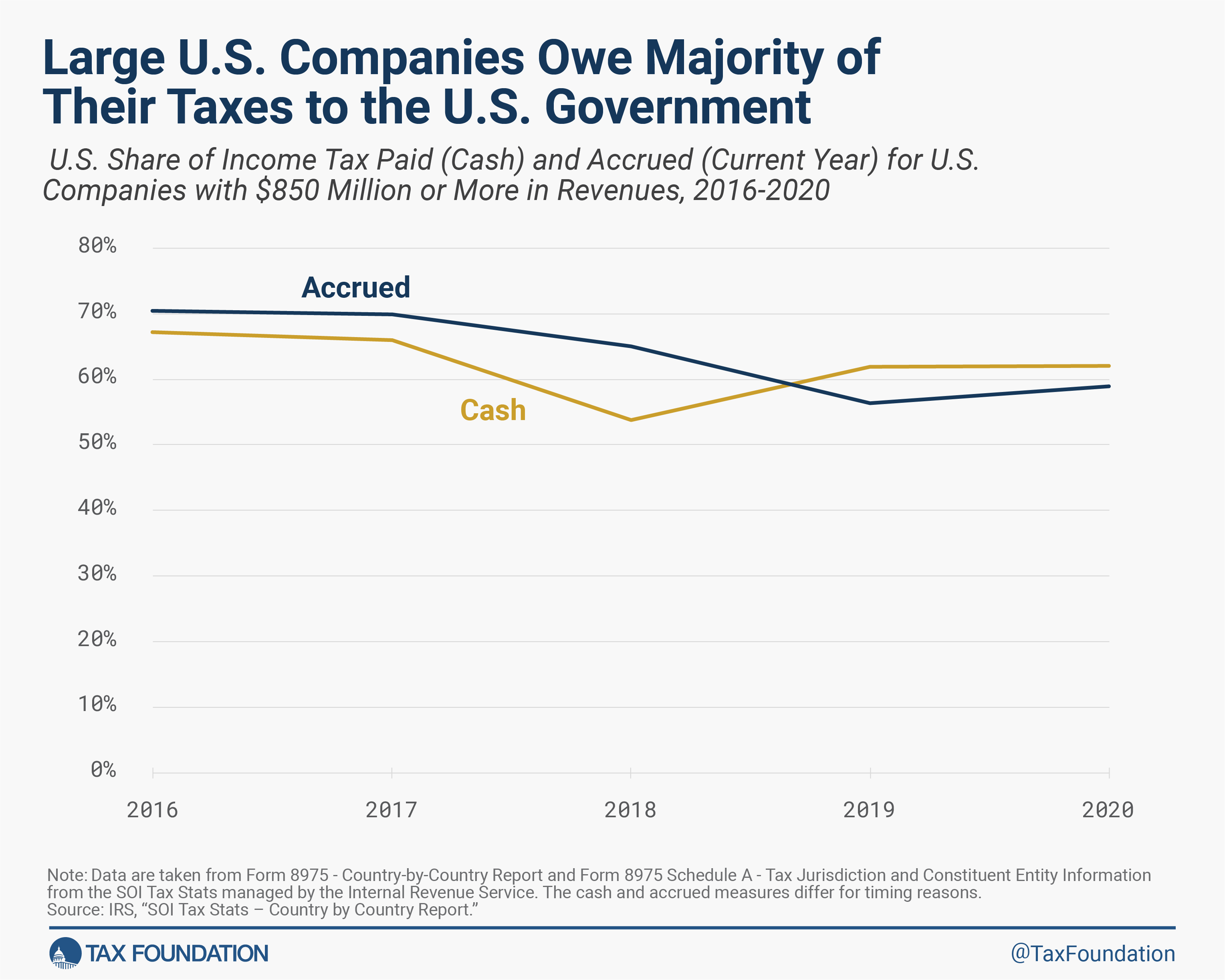

Canceling the tightening of FDII/GILTI

All three provisions of the international tax system overhaul—global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI), the foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) deduction, and the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT)—are scheduled to become more restrictive after December 31, 2025.[3]

The effective tax rate under GILTI is scheduled to rise from 10.5 percent to 13.125 percent. The reduced rate on foreign profits derived from U.S. intangibles under FDII is scheduled to increase from 13.125 percent to 16.406 percent. The rate at which the BEAT is levied on multinational companies is scheduled to rise from 10 percent to 12.5 percent.

In this paper, we model retaining the current policy tax rates for GILTI (10.5 percent) and FDII (13.125 percent); we do not model any changes to BEAT due to model limitations.

Economic, Revenue, and Distributional Impact of Canceling Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Business Tax Increases

We find making 100 percent bonus depreciation permanent, canceling R&D amortization and the tighter interest deduction limit, and retaining current policy GILTI and FDII tax rates would raise long-run GDP by 0.6 percent. Long-run gross national product (GNP), a measure of American incomes, would increase by 0.5 percent, while the capital stock and wages would grow by 1 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively. The changes would also create about 105,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

The most economically beneficial provision is making 100 percent bonus depreciation permanent, which would increase long-run GDP by 0.4 percent and create about 73,000 full-time equivalent jobs. Our estimates and the economic literature suggest full cost recovery for investments is one of the most pro-growth tax policies relative to the cost.[4]

| Provision | Change in GDP | Change in GNP | Change in Capital Stock | Change in Wages | Change in Full-Time Equivalent Jobs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Make 100 percent bonus depreciation permanent | +0.4% | +0.3% | +0.7% | +0.3% | +73,000 |

| Cancel R&D amortization | +0.1% | +0.1% | +0.2% | +0.1% | +15,000 |

| Cancel interest deduction limitation switch from EBITDA to EBIT | Less than +0.05% | Less than +0.05% | +0.1% | Less than +0.05% | +8,000 |

| Retain current policy GILTI and FDII deductions | +0.1% | +0.1% | +0.1% | +0.1% | +9,000 |

| Total Economic Effect | +0.6% | +0.5% | +1.0% | +0.5% | +105,000 |

| Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, October 2022. Items may not sum due to rounding. | |||||

We estimate canceling the major TCJA business tax increases would reduce federal revenue by about $751 billion over 10 years on a conventional basis. The two most costly provisions over the budget window are making 100 percent bonus depreciation permanent (about $402 billion) and canceling R&D amortization ($181 billion). Canceling the tighter limitation on interest deductions would cost about $69 billion over 10 years and retaining current policy GILTI and FDII rates would cost about $100 billion over the budget window.[5]

In the long run, the cost of the expensing provisions is lower than the 10-year cost, which is frontloaded due to changing the timing of when firms deduct costs from taxable income.[6] For example, the cost of permanent 100 percent bonus depreciation falls from $66.2 billion in 2027 to $24.9 billion in 2032, and R&D amortization cancelation from $60 billion in 2023 to $6.8 billion in 2032.

On a dynamic basis, we find canceling the tax increases would cost about $568 billion over the next 10 years. The lower dynamic cost is driven by higher economic growth, which increases individual income and payroll tax revenue and partially offsets the cost of the tax changes. By 2032, the dynamic cost is about $21 billion, less than half of the conventional cost in that year.

In the long run, permanent 100 percent bonus depreciation would have a conventional annual cost of about $12.8 billion in 2022 dollars and would produce about $150 billion annually in additional economic output in 2022 dollars. The large increase in economic output makes permanent bonus depreciation a highly cost-effective tax cut.

In the long run, permanent bonus depreciation would raise about $31 billion annually in 2022 dollars on a dynamic basis. The debt-to-GDP ratio would fall from 185 percent in 2052 under the baseline to 183.6 percent, driven by the larger economy under permanent bonus depreciation.

For the entire package, canceling TCJA business tax increases would increase the debt-to-GDP ratio in 2052 from 185 percent to 188.2 percent on a conventional basis, costing about $2.4 trillion over the next 30 years after interest costs. On a dynamic basis, the package would cost about $93 billion over the next 30 years after interest costs. The debt-to-GDP ratio in 2052 would fall from 185 percent to 184.2 percent despite the cost due to a larger economy.

| Conventional Revenue | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2023 – 2032 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent 100% Bonus Depreciation | -$19.9 | -$35.7 | -$47.1 | -$56.9 | -$66.2 | -$50.4 | -$39.9 | -$32.7 | -$27.9 | -$24.9 | -$401.5 |

| Permanent Cancelation of R&D Amortization | -$60.0 | -$38.3 | -$25.8 | -$16.8 | -$9.0 | -$5.3 | -$5.8 | -$6.3 | -$6.7 | -$6.8 | -$180.8 |

| Cancel Interest Deduction Limitation Switch from EBITDA to EBIT | -$7.1 | -$6.3 | -$5.8 | -$5.5 | -$5.2 | -$6.1 | -$7.0 | -$7.8 | -$8.7 | -$8.9 | -$68.5 |

| Retain Current Policy GILTI & FDII Rates | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | -$13.3 | -$13.3 | -$13.6 | -$14.1 | -$14.7 | -$15.2 | -$15.7 | -$100.0 |

| Total Conventional Revenue | -$87.0 | -$80.3 | -$78.7 | -$92.6 | -$93.7 | -$75.5 | -$66.8 | -$61.5 | -$58.4 | -$56.3 | -$750.8 |

| Dynamic Revenue | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2023 – 2032 |

| Permanent 100% Bonus Depreciation | -$19.8 | -$35.2 | -$43.5 | -$50.3 | -$55.7 | -$37.9 | -$25.3 | -$16.0 | -$9.2 | -$4.1 | -$296.8 |

| Permanent Cancelation of R&D Amortization | -$59.8 | -$38.0 | -$24.5 | -$15.2 | -$6.9 | -$2.9 | -$3.0 | -$3.1 | -$3.0 | -$2.7 | -$159.1 |

| Cancel Interest Deduction Limitation Switch from EBITDA to EBIT | -$6.7 | -$5.9 | -$5.3 | -$4.9 | -$4.5 | -$3.2 | -$3.4 | -$3.4 | -$3.4 | -$3.5 | -$44.2 |

| Retain Current Policy GILTI & FDII Rates | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | -$9.0 | -$9.0 | -$9.2 | -$9.5 | -$9.9 | -$10.2 | -$10.6 | -$67.5 |

| Total Dynamic Revenue | -$86.3 | -$79.0 | -$73.2 | -$79.3 | -$76.0 | -$53.2 | -$41.2 | -$32.4 | -$25.9 | -$20.9 | -$567.5 |

| Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, October 2022. | |||||||||||

We find that canceling the TCJA business tax changes would raise after-tax incomes across the income spectrum. In 2023, after-tax incomes would increase by 0.6 percent overall, with a 0.4 percent increase for the bottom 20 percent of taxpayers and a 1.7 percent increase for the top 1 percent. In 2032, the rise in after-tax incomes is somewhat smaller due to the timing effect associated with permanent 100 percent bonus depreciation and canceling R&D amortization.

In the long run, after-tax incomes increase both due to the tax changes themselves and the higher economic output and incomes produced by the tax changes. We find after-tax incomes would rise by 0.6 percent overall, including a 0.6 percent increase for the bottom 20 percent of taxpayers and a 1 percent increase for the top 1 percent.

| Income Group | 2023, Conventional | 2032, Conventional | Long-run, Dynamic |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% to 20% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.6% |

| 20% to 40% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.6% |

| 40% to 60% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.6% |

| 60% to 80% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.6% |

| 80% to 90% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.6% |

| 90% to 95% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.6% |

| 95% to 99% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.7% |

| 99% to 100% | 1.7% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

| Total | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.6% |

| Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, October 2022. | |||

Conclusion

The business tax changes originally introduced in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are scheduled to increase tax burdens on businesses at a time when economic headwinds and broader uncertainty are higher than they have been in decades.

We find making 100 percent bonus depreciation permanent, canceling R&D amortization and the tighter limitation on interest deductions, and retaining current law international tax rates would increase long-run economic output by 0.6 percent and raise after-tax incomes across the board.

The changes would cost about $751 billion over the next 10 years conventionally, but in the long run, the cost is lower as economic output increases and the transition effects of making 100 percent bonus depreciation and R&D expensing permanent fade. Additionally, taxpayers would benefit from a stable business tax system, rather than one ridden with scheduled tax policy changes and shifts.

Methodology

Tax Foundation’s General Equilibrium Model computes tax items related to investment and cost recovery. Using historical investment since 1960 across 95 asset types and 14 major industry groups, as well as current and historical cost recovery rules for each asset type, the model calculates tax depreciation deductions, amortization of intangible assets, and the research credit for each year.

The calculations capture the effects of detailed policy changes for capital cost recovery: changes to depreciation rules, such as the method or class life; rates; and eligibility. The most recent update in the corporate capital model can simulate the take-up of bonus depreciation, eligibility and use of section 179 expensing, expensing and amortization of intellectual property investment, and rules of the regular and alternative research tax credits.

The model draws on detailed fixed asset investment data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, with an adjustment to reflect differential growth rates of investment by corporations compared to other businesses. To reconcile the data with depreciation deductions reported by the IRS (using slightly different industry definitions and only C corporations), we jointly scale the data and calibrate the bonus depreciation take-up rates by industry and by type of business (domestic vs. foreign-owned), to target IRS depreciation deductions for each year from 2007-2013.

When simulating the revenue and economic effects of 100 percent bonus depreciation and canceling R&D amortization, the take-up rate for the non-corporate sector is derived using data from the Treasury Department and is calibrated against the data derived from the corporate tax model.[7]

[1] Alex Muresianu and Garrett Watson, “To Stimulate R&D Investment, Stop Penalizing it in the Tax Code,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 16, 2022,

[2] Erica York, Huaqun Li, Daniel Bunn, Garrett Watson, and Cody Kallen, “Economic, Revenue, and Distributional Impact of Permanent 100 Percent Bonus Depreciation,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 30, 2022,

[3] Cody Kallen, “Options for Reforming the Taxation of U.S. Multinationals,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 12, 2021,

[4] Erica York, “Reviewing the Benefits of Full Expensing for the Post-Pandemic Economic Recovery,” Tax Foundation, April 27, 2020,

[5] When estimating the revenue cost of retaining EBITDA as the tax base for the interest limitation deduction, we adopt the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) interest rate forecast. If interest rates increase beyond the CBO forecast in the coming years, we expect the revenue cost may be higher than our estimate.

[6] Kyle Pomerleau, “Full Expensing Costs Less Than You’d Think,” Tax Foundation, Jun. 13, 2017,

[7] John Kitchen and Matthew Knittel, “Business Use of Section 179 Expensing and Bonus Depreciation, 2002-2014,” Department of the Treasury, October 2016,